Interview

Shaking the Dust: AN INTERVIEW WITH Anis Mojgani

BY Mitchell G. Layton & Gabrielle Lund

2016

photo by Natalie Seeboth

photo by Natalie Seeboth

“I strive to offer myself up to my audience in a manner that allows them to come inside whatever room I am offering to them, I want to invite folks in and make them comfortable.” So says spoken word artist, Anis Mojgani, who is a two-time national slam poetry champion and has released four poetry collections with Write Bloody publications. He has performed in competitions, the “Heavy and Light” tour for To Write Love on Her Arms, and even for the United Nations.

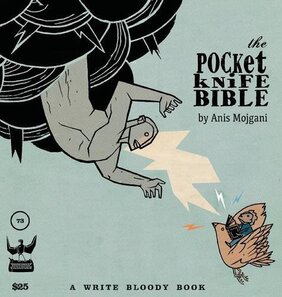

In wake of the release of his newest book, The Pocketknife Bible, he was kind enough to talk to Glassworks about the experience of revisiting his childhood, his return to the art of graphic novella, the way his performance poems transfer onto the page, and the message he hopes to leave with his audience through a variety of mediums.

In wake of the release of his newest book, The Pocketknife Bible, he was kind enough to talk to Glassworks about the experience of revisiting his childhood, his return to the art of graphic novella, the way his performance poems transfer onto the page, and the message he hopes to leave with his audience through a variety of mediums.

Glassworks Magazine (GM): You earned a bachelor's degree in fine arts of comic books at the Savannah College of Art and Design, and your newest book, The Pocketknife Bible, is a combination of both prose poetry and graphic novella. What was it like to combine these two interests for one purpose?

Anis Mojgani (AM): It was a difficult endeavor, but not so much for the combination factor. Much of the work that I am interested in creating through the medium of comics and sequential art is rooted in the same work as my poetry, so it's not really two different interests combining in one purpose. I think poetry is actually a very natural form to engage in with pictures, a very natural marriage between text and visual. Poetry is an interactive art form that is based very much on using the space between images, ideas, and sentences to allow the audience's imagination to take roost and contribute to the story they are reading. The form of comics is built in the exact same way, juxtaposing one image with another, juxtaposing one image with a collection of words, in order to build a story in the mind of its reader.

Difficulties arose more in that it has simply been a long time since visual arts and illustrative storytelling has been a consistent part of my creative life. Having to get used to flexing that part of my brain and my heart was something of a challenge, especially carrying the awareness that whatever early endeavors into the visual aspect of the book, would largely serve as preparatory work and thus feel like busy work as opposed to fun creative exploration. Sort of like being away from running for a long time and feeling like you want to get back into it, even though knowing those first runs are going to royally suck.

GM: So you had to get back into the art of graphic novella, much like you had to get back into the mindset of a child for writing your newest book. What was it like writing a book about childhood as an adult, and do you think the process of writing it helped you relive your childhood in a way?

AM: There was definitely an aspect of such, maybe not reliving it, but engaging more deeply into memory than some of my work in the past. While so much of my work has already explored childhood, seeking to connect with it in the manner needed for this book and also making an effort to stir up new memories and solidify more clearly ones that were already present, brought it to life in a different sort of way.

GM: There are three sections in The Pocketknife Bible. What does each one bring to life and how did you decide on dividing them?

AM: The book is separated into three parts that consist of:

GM: Interaction seems to be an essential part of both writing and performing for you. In interacting with your audience at live performances, have you witnessed a difference in their response after reading one of your books as opposed to watching you perform and how do you think your audience will respond to your newest book and the prose-poetry in it?

AM: It's hard to say, as I'm not present with people when they're reading my books. I can say that I am always grateful and happy when my work is found by people in written form and that they reveal to me that they have connected with it. Regarding this new book, I don't know. I know I'm excited to share something new and different than some of my other work, with my audience.

Anis Mojgani (AM): It was a difficult endeavor, but not so much for the combination factor. Much of the work that I am interested in creating through the medium of comics and sequential art is rooted in the same work as my poetry, so it's not really two different interests combining in one purpose. I think poetry is actually a very natural form to engage in with pictures, a very natural marriage between text and visual. Poetry is an interactive art form that is based very much on using the space between images, ideas, and sentences to allow the audience's imagination to take roost and contribute to the story they are reading. The form of comics is built in the exact same way, juxtaposing one image with another, juxtaposing one image with a collection of words, in order to build a story in the mind of its reader.

Difficulties arose more in that it has simply been a long time since visual arts and illustrative storytelling has been a consistent part of my creative life. Having to get used to flexing that part of my brain and my heart was something of a challenge, especially carrying the awareness that whatever early endeavors into the visual aspect of the book, would largely serve as preparatory work and thus feel like busy work as opposed to fun creative exploration. Sort of like being away from running for a long time and feeling like you want to get back into it, even though knowing those first runs are going to royally suck.

GM: So you had to get back into the art of graphic novella, much like you had to get back into the mindset of a child for writing your newest book. What was it like writing a book about childhood as an adult, and do you think the process of writing it helped you relive your childhood in a way?

AM: There was definitely an aspect of such, maybe not reliving it, but engaging more deeply into memory than some of my work in the past. While so much of my work has already explored childhood, seeking to connect with it in the manner needed for this book and also making an effort to stir up new memories and solidify more clearly ones that were already present, brought it to life in a different sort of way.

GM: There are three sections in The Pocketknife Bible. What does each one bring to life and how did you decide on dividing them?

AM: The book is separated into three parts that consist of:

- Part one: stacked observations of my childhood from the direct point of view of me as a child, which serves as an introduction and establishing of that world for the reader.

- Part two: taking some of the themes of the book and/or poems that were not included in the book, and creating illustrations out of them, sort of pictorial poems.

- Part three: is the culmination of the book where me as a boy and me as an adult are able to cross paths and interact with one another.

GM: Interaction seems to be an essential part of both writing and performing for you. In interacting with your audience at live performances, have you witnessed a difference in their response after reading one of your books as opposed to watching you perform and how do you think your audience will respond to your newest book and the prose-poetry in it?

AM: It's hard to say, as I'm not present with people when they're reading my books. I can say that I am always grateful and happy when my work is found by people in written form and that they reveal to me that they have connected with it. Regarding this new book, I don't know. I know I'm excited to share something new and different than some of my other work, with my audience.

"I'm always grateful and happy when my work is found by people in written form and that they reveal to me that they have connected with it." |

GM: When it comes to sharing your work with your audience, you memorize your poems for performance. Would you say that memorizing every word of your performance pieces makes them more intimate to you? Do you feel that this intimacy carries into the space you make for your audience? Or are these pieces more of a natural bit of information you carry along with you that become closer to you over time?

|

AM: Both. I think it's easier to memorize pieces of writing that began in oneself, so definitely the poems are a bit of that information of myself that are naturally already there. The pieces are definitely able to become more intimate to myself and then thus to my audience, by not having an anchor of paper to hold on to as I share them. I don't mind reading poems from my books, and some piece I think are shared more strongly because of such, but definitely having them in my memory of mind and body enables the poems to be more present.

GM: Your ability to make your poems present is part of what made you a two-time National Poetry Slam Champion. Why did you choose to perform your poems rather than just to write them? What elements of the stage intrigue you?

AM: There isn't an either/or. I write poems and sometimes I perform them based on what excites me and what pieces I think will revel in being listened to live. I love the stage because it allows me to create with my audience something completely new and singular to us sharing time and space together, that my poem on its own would not create. I also think art enables itself, its artists, and its audiences to be carried further when it engages with vulnerability and sharing my poems live allow that vulnerability to take greater shape.

GM: That vulnerability is what gained our attention when we first saw you perform, and it’s what led us to one of your most popular poems: “Shake the Dust.” We were drawn to it because it is a bright and energetic poem that focuses on perseverance, forward movement, and “shaking the dust” off. When you were writing this, what meaning did it have for you? And did you anticipate its popularity?

AM: I wrote “Shake the Dust” when I was probably 22 or so, which is now more than 15 years ago, so I can no longer speak directly to its creation or the experience of writing it. There was no way for me to anticipate the popularity it grew to have. It was simply another poem I was writing, one that wanted to speak to ideas on self-worth and beliefs in the nobility of all of us, regardless and in spite of the possibility of our lives telling us the opposite.

GM: The way you speak to the idea of self-worth is inspiring, but so are the techniques you use to convey it. “Shake the Dust,” like some of your other poems, uses lists and repetition to keep the audiences’ interest. Do you feel your other list poems such as “Direct Orders” and “& then Billy explained to me the parts of a gun” translate as well on the page?

AM: I don't think all my poems translate as well to the page, though it just sort of depends on when in my life I wrote them. Some of my older ones are pieces I wrote when there was often more intent to bring the words to a stage and as such, that intent helped to shape them.

Interesting choice on “& then Billy explained to me the parts of a gun,” as I don't think I've ever performed that poem. "Direct Orders" though is definitely a poem I wrote at a time when I was writing poems with the intent and knowledge that they would probably exist on stage.

GM: Your ability to make your poems present is part of what made you a two-time National Poetry Slam Champion. Why did you choose to perform your poems rather than just to write them? What elements of the stage intrigue you?

AM: There isn't an either/or. I write poems and sometimes I perform them based on what excites me and what pieces I think will revel in being listened to live. I love the stage because it allows me to create with my audience something completely new and singular to us sharing time and space together, that my poem on its own would not create. I also think art enables itself, its artists, and its audiences to be carried further when it engages with vulnerability and sharing my poems live allow that vulnerability to take greater shape.

GM: That vulnerability is what gained our attention when we first saw you perform, and it’s what led us to one of your most popular poems: “Shake the Dust.” We were drawn to it because it is a bright and energetic poem that focuses on perseverance, forward movement, and “shaking the dust” off. When you were writing this, what meaning did it have for you? And did you anticipate its popularity?

AM: I wrote “Shake the Dust” when I was probably 22 or so, which is now more than 15 years ago, so I can no longer speak directly to its creation or the experience of writing it. There was no way for me to anticipate the popularity it grew to have. It was simply another poem I was writing, one that wanted to speak to ideas on self-worth and beliefs in the nobility of all of us, regardless and in spite of the possibility of our lives telling us the opposite.

GM: The way you speak to the idea of self-worth is inspiring, but so are the techniques you use to convey it. “Shake the Dust,” like some of your other poems, uses lists and repetition to keep the audiences’ interest. Do you feel your other list poems such as “Direct Orders” and “& then Billy explained to me the parts of a gun” translate as well on the page?

AM: I don't think all my poems translate as well to the page, though it just sort of depends on when in my life I wrote them. Some of my older ones are pieces I wrote when there was often more intent to bring the words to a stage and as such, that intent helped to shape them.

Interesting choice on “& then Billy explained to me the parts of a gun,” as I don't think I've ever performed that poem. "Direct Orders" though is definitely a poem I wrote at a time when I was writing poems with the intent and knowledge that they would probably exist on stage.

GM: The stage fits the intent of your poems, and you’ve performed in many different environments, like competitions or shows like TWLOHA’s “Heavy and Light” and TEDx events. Which environment do you feel most comfortable in, and which setting do you feel is best for your medium of spoken word?

AM: Any environment that is intended for performative arts that is filled with an audience that is there to listen and engage and experience live poetry is going to always be the best setting.

For me, I love being in spaces such as that and having the opportunity to travel an extended period of time with my audience, so more show environments, where I get to craft an longer experience with my audience, is where I feel most comfortable.

GM: In your poem “On the Day His Son Was Born the Astronomer Screamed Out His Window,” you write, “Cussing doesn’t come from a lack of vocabulary—I know all the other words.” You use cursing occasionally in your poems, sometimes creating a bit of shock value. How has cursing affected your poems and your performance of them? And would you still use cursing in your poems if they were only written, not performed?

AM: I use whichever words are going to communicate best that which I am trying to communicate. Sometimes those are curse words, and this doesn't matter whether a poem is written or performed. That being said, there are some words that have better sounds inherent to them. Again some of them are curse words and some are not. However, even when read, those words carry a sound in our heads and silently in our mouths, and as such when writing, that plays a part in the poem as well.

GM: In addition to the sounds of your words and word choices, the themes you choose for your poetry are also interesting. Many of your poems seem to focus on the themes of existence, rejuvenation, and change. In your poem, “Closer,” you write, “There is a doorknob glowing like chance./ Clutch it./ Turn and pull./ Step through./ Chin up./ Back straight./ Eyes open./ Hearts loud./ Walk through this with me.” What do you intend to walk through with the reader? And do you write poems to inspire change in your readers?

AM: The “this” is simply life, living, and the experience of it.

I am always writing poems to inspire change, whether that is change of opinion, of mind, heart, or whatever––always writing to insert something into a person that they might be prompted to investigate a dialogue within themselves and/or with others.

AM: Any environment that is intended for performative arts that is filled with an audience that is there to listen and engage and experience live poetry is going to always be the best setting.

For me, I love being in spaces such as that and having the opportunity to travel an extended period of time with my audience, so more show environments, where I get to craft an longer experience with my audience, is where I feel most comfortable.

GM: In your poem “On the Day His Son Was Born the Astronomer Screamed Out His Window,” you write, “Cussing doesn’t come from a lack of vocabulary—I know all the other words.” You use cursing occasionally in your poems, sometimes creating a bit of shock value. How has cursing affected your poems and your performance of them? And would you still use cursing in your poems if they were only written, not performed?

AM: I use whichever words are going to communicate best that which I am trying to communicate. Sometimes those are curse words, and this doesn't matter whether a poem is written or performed. That being said, there are some words that have better sounds inherent to them. Again some of them are curse words and some are not. However, even when read, those words carry a sound in our heads and silently in our mouths, and as such when writing, that plays a part in the poem as well.

GM: In addition to the sounds of your words and word choices, the themes you choose for your poetry are also interesting. Many of your poems seem to focus on the themes of existence, rejuvenation, and change. In your poem, “Closer,” you write, “There is a doorknob glowing like chance./ Clutch it./ Turn and pull./ Step through./ Chin up./ Back straight./ Eyes open./ Hearts loud./ Walk through this with me.” What do you intend to walk through with the reader? And do you write poems to inspire change in your readers?

AM: The “this” is simply life, living, and the experience of it.

I am always writing poems to inspire change, whether that is change of opinion, of mind, heart, or whatever––always writing to insert something into a person that they might be prompted to investigate a dialogue within themselves and/or with others.