Interview

Nurturing Peace in a Hostile World: aN INTERVIEW WITH Artress Bethany White

BY Gianna Forgen, Courtney R. Hall, and Kelli Hughes

March 2024

|

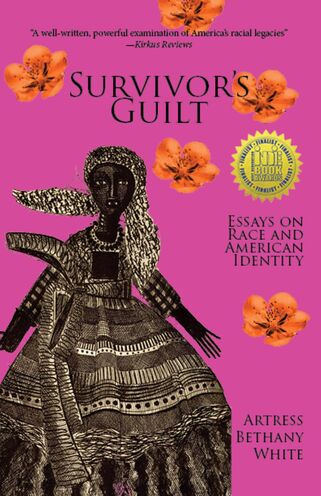

In the age of surging book bans and sanitized school curricula, diverse narratives which challenge a universal experience are needed now more than ever. Artress Bethany White knows the value of shared stories and how they can open people’s eyes to new perspectives they may not have encountered elsewhere. As a poet, essayist, educator, and mother, White draws from her experiences and the shared trauma of marginalized people in her 2022 Next Generation Finalist Indie Book Award winning essay collection Survivor’s Guilt: Essays on Race and American Identity.

|

In this interview with Glassworks, White touches on many aspects of the hostile world we live in, and how she uses her writing and work as both an educator and a mother to foster peace wherever and whenever she can.

|

Glassworks Magazine (GM): Your essay collection Survivor’s Guilt: Essays on Race and American Identity explores the complexities of racial identity and the longevity of racism in the United States. In the introduction to the collection, you assert that “true understanding [could] be only a shared story away.” How would you define “true understanding,” particularly as it relates to the experiences of people of color, immigrants, and/or other marginalized communities in the United States? Since the publication of your essay collection in 2020, have you come across any shared stories that allowed you to understand a perspective or experience you were previously unaware of?

Artress Bethany White (ABW): I am a firm believer in people gaining cultural understanding from experiencing the stories of others. This probably stems from years spent teaching in classrooms where wonderful, life-changing stories were shared among a diverse student body. I have witnessed the right story diffusing long-held stereotypes and biases. These stories can also be introduced through poems, novels, essays, and film. The “true” in understanding is a story that has the power to cut deftly through the baggage of toxic belief systems. For my own use, I look for stories that wed transparency and craft. The story, regardless of genre, must deliver on that insider point of view that bellows authenticity. A favorite essay that does this work is Wesley Morris’s "My Mustache, My Self" published in The New York Times Magazine. |

GM: “Sonny Boy” is an essay in the collection where you unpack the trauma of gun violence and the death of a loved one. You write, “Often tragic stories are put on a shelf, ostensibly to protect the psyches of the young and the living.” Through your writing and interviews, it is apparent you strongly believe in properly educating today’s youth so that they can grow up to be tolerant and empathetic adults. When writing, have you ever censored yourself for the sake of a less than tolerant or educated audience? Was a goal in writing these essays to add to the texts you—or others—might recommend to people looking to educate themselves on race issues in America?

ABW: I worked to be true to the experiences I brought to life on the page in Survivor’s Guilt. I wasn’t consciously thinking about censoring myself at all. I wanted people to read the book and be convicted of its veracity in the process. I took risks, which is what I think you have to do if you want to touch people where they live. Making some book suggestions was important, but there are so many I could have named, so those mentioned do not constitute an exhaustive list by any means. I tended to mention books that had worked well in the classroom, led to lively, engaged discussion, and were written by authors whom I respect.

GM: This essay collection not only educates others about race issues, it also shares your family history, your personal experiences, and explains why giving people access to multiple perspectives is a vital aspect of teaching and talking about marginalized voices, especially in more contemporary works. How have you seen literature elsewhere in the educational sphere start to shift towards more diverse and contemporary voices, and what do you think prevents educators from making the leap to promote those voices?

ABW: I have seen the most growth in education programs focused on training and bringing new teachers into the field. I think universities have finally realized that if current educators are unskilled at teaching diverse voices, those working with future educators at the university level are the reason that the training did not take place. I also think that educators in MFA programs are doing this important work, as more and more faculty from marginalized communities are being hired in these programs. Additionally, I believe that the use of more diverse voices in post-secondary classrooms is a direct result of a more inclusive body of writers being represented on the lists of prestigious literary awards after decades when this was not the case.

ABW: I worked to be true to the experiences I brought to life on the page in Survivor’s Guilt. I wasn’t consciously thinking about censoring myself at all. I wanted people to read the book and be convicted of its veracity in the process. I took risks, which is what I think you have to do if you want to touch people where they live. Making some book suggestions was important, but there are so many I could have named, so those mentioned do not constitute an exhaustive list by any means. I tended to mention books that had worked well in the classroom, led to lively, engaged discussion, and were written by authors whom I respect.

GM: This essay collection not only educates others about race issues, it also shares your family history, your personal experiences, and explains why giving people access to multiple perspectives is a vital aspect of teaching and talking about marginalized voices, especially in more contemporary works. How have you seen literature elsewhere in the educational sphere start to shift towards more diverse and contemporary voices, and what do you think prevents educators from making the leap to promote those voices?

ABW: I have seen the most growth in education programs focused on training and bringing new teachers into the field. I think universities have finally realized that if current educators are unskilled at teaching diverse voices, those working with future educators at the university level are the reason that the training did not take place. I also think that educators in MFA programs are doing this important work, as more and more faculty from marginalized communities are being hired in these programs. Additionally, I believe that the use of more diverse voices in post-secondary classrooms is a direct result of a more inclusive body of writers being represented on the lists of prestigious literary awards after decades when this was not the case.

"I wasn’t consciously thinking about censoring myself at all. I wanted people to read the book and be convicted of its veracity in the process. I took risks, which is what I think you have to do if you want to touch people where they live."

GM: To expand on that topic, we are now more than ever bearing witness to books written by and about people of color, the LGBTQ+ community, and other marginalized voices being banned in schools vehemently in multiple states. Aside from limiting children’s access to other perspectives and educating them about important parts of American history, how do you think these book bans impact youth literacy as a whole?

ABW: I make a point of teaching banned titles, especially to future educators. I let them know it is important to be prepared, no matter what politics are trending. As far as youth and their response to the bans, many of the students pursuing undergraduate degrees now came of age in high schools where members of the student body actively advocated for the LGBTQ+ community in regard to gender-neutral bathrooms and supported Black Lives Matter advocacy. As a result, they read to uphold their beliefs and continue to think independently of prevailing conservative and biased politics. That said, there are students who came of age in rural and politically oppressive regions who did not have the privilege of being exposed to diverse voices, nor was empathy cultivated as an intellectual and life skill. I will always be an advocate for cultivating diverse readers, and my literary projects reflect this.

GM: In the essay “Survivor’s Guilt in the Age of Terrorism,” you write that following the Pulse nightclub shooting, your “plan to thwart homophobia through intellectual growth seemed like a drop in the bucket in the face of hatred behind an automatic weapon.” This book seems to be almost in response to that feeling; even in the fear of what has happened, you have continued to contribute to the intellectual growth of others, and then written about it, too. What similarities and/or differences do you find in working to counter bigotry in writing compared to teaching?

ABW: When teaching, you always have the benefit of a live audience ready to engage questions and participate in open discussion. It is a dynamic environment that can result in all kinds of discursive threads being introduced into the room. This is definitely not the case when writing for a broad and anonymous audience. When writing you have to imagine the questions or directions a reader’s thoughts might take and weave that predictive element into your narrative. It takes a lot of time, rereading, and revision to do that work on the page and not lose your intended focus and plan for the text. For me, use of the anecdotal experience was the best way to engage this level of multitasking on the page.

GM: You skillfully capture the subtleties of racial microaggressions and the nuances of racism in your writing. Could you share how you employ literary techniques or storytelling strategies to convey these subtle yet impactful moments? What kind of response or discussion have you observed from your readers as a result?

ABW: The anecdotal was an essential craft element in the book. Documenting your personal experience is a powerful platform from which to speak on issues of racial bias, particularly if you are a person of color. Reading memoir gives people an opportunity to have a controlled yet intimate relationship with a person outside of their usual in-group, and that experience can result in a more confident, real-world experience.

I have enjoyed so much positive feedback from the essays contained in Survivor’s Guilt. Particular essays that have sparked deep discussions because they deal with lesser- known histories and realities for a younger generation include “A Lynching in North Carolina,” “American Noir,” and “Pull and Drag.” I think people have responded most favorably to how much information is delivered in the short, personal essay form, and that the essays are meant to serve as a catalyst for further study.

ABW: I make a point of teaching banned titles, especially to future educators. I let them know it is important to be prepared, no matter what politics are trending. As far as youth and their response to the bans, many of the students pursuing undergraduate degrees now came of age in high schools where members of the student body actively advocated for the LGBTQ+ community in regard to gender-neutral bathrooms and supported Black Lives Matter advocacy. As a result, they read to uphold their beliefs and continue to think independently of prevailing conservative and biased politics. That said, there are students who came of age in rural and politically oppressive regions who did not have the privilege of being exposed to diverse voices, nor was empathy cultivated as an intellectual and life skill. I will always be an advocate for cultivating diverse readers, and my literary projects reflect this.

GM: In the essay “Survivor’s Guilt in the Age of Terrorism,” you write that following the Pulse nightclub shooting, your “plan to thwart homophobia through intellectual growth seemed like a drop in the bucket in the face of hatred behind an automatic weapon.” This book seems to be almost in response to that feeling; even in the fear of what has happened, you have continued to contribute to the intellectual growth of others, and then written about it, too. What similarities and/or differences do you find in working to counter bigotry in writing compared to teaching?

ABW: When teaching, you always have the benefit of a live audience ready to engage questions and participate in open discussion. It is a dynamic environment that can result in all kinds of discursive threads being introduced into the room. This is definitely not the case when writing for a broad and anonymous audience. When writing you have to imagine the questions or directions a reader’s thoughts might take and weave that predictive element into your narrative. It takes a lot of time, rereading, and revision to do that work on the page and not lose your intended focus and plan for the text. For me, use of the anecdotal experience was the best way to engage this level of multitasking on the page.

GM: You skillfully capture the subtleties of racial microaggressions and the nuances of racism in your writing. Could you share how you employ literary techniques or storytelling strategies to convey these subtle yet impactful moments? What kind of response or discussion have you observed from your readers as a result?

ABW: The anecdotal was an essential craft element in the book. Documenting your personal experience is a powerful platform from which to speak on issues of racial bias, particularly if you are a person of color. Reading memoir gives people an opportunity to have a controlled yet intimate relationship with a person outside of their usual in-group, and that experience can result in a more confident, real-world experience.

I have enjoyed so much positive feedback from the essays contained in Survivor’s Guilt. Particular essays that have sparked deep discussions because they deal with lesser- known histories and realities for a younger generation include “A Lynching in North Carolina,” “American Noir,” and “Pull and Drag.” I think people have responded most favorably to how much information is delivered in the short, personal essay form, and that the essays are meant to serve as a catalyst for further study.

GM: In your interview with JMMW, you discuss your identity as a multi-genre writer and share insights into your decision-making process when selecting between prose and poetry for a particular topic. Could you elaborate on how your creative process guides you in determining the most suitable genre for your work? Have there been instances where you initially settled on one genre, only to reconsider and try again with another?

ABW: There was a time when I believed that I had to exclusively deal with certain stories only in a particular genre, so I had to choose carefully because I would only get one shot. I have since learned from my own process, as well as following the literary development of some of my favorite authors, that this is definitely not the case. In that interview, I mentioned that working on a book-length treatment of my family’s slave history led me to cast the work in poetry because it was emotionally charged, and many of the stories came to me in fragmentary impressions. I stand by that statement, but I also would not close the door on one day exploring the same subject matter in prose down the road. Conversely, I immediately knew Survivor’s Guilt would be a prose project because I needed the more expansive possibilities of the essay to allow me to explore complex ideas over the course of pages without coming across as too didactic. I will note, however, that people have commented on the poetic nature of my essays, which I believe comes from the fact of their brevity, and a highly lucid narrative form.

ABW: There was a time when I believed that I had to exclusively deal with certain stories only in a particular genre, so I had to choose carefully because I would only get one shot. I have since learned from my own process, as well as following the literary development of some of my favorite authors, that this is definitely not the case. In that interview, I mentioned that working on a book-length treatment of my family’s slave history led me to cast the work in poetry because it was emotionally charged, and many of the stories came to me in fragmentary impressions. I stand by that statement, but I also would not close the door on one day exploring the same subject matter in prose down the road. Conversely, I immediately knew Survivor’s Guilt would be a prose project because I needed the more expansive possibilities of the essay to allow me to explore complex ideas over the course of pages without coming across as too didactic. I will note, however, that people have commented on the poetic nature of my essays, which I believe comes from the fact of their brevity, and a highly lucid narrative form.

"Conversely, I immediately knew Survivor’s Guilt would be a prose project because I needed the more expansive possibilities of the essay to allow me to explore complex ideas over the course of pages without coming across as too didactic."

GM: Aside from being an essayist, you wear many hats: poet, educator, and nonfiction editor for Pangyrus, to name a few. Has one of these roles taken precedent in your life recently? Can you speak to an upcoming project?

ABW: Beyond my collection of essays Survivor’s Guilt: Essays on Race and American Identity, I am currently co-editor of an anthology with poet Danielle Legros Georges to be published before the new year, Wheatley at 250: Black Women Poets Re-Imagine the Verse of Phillis Wheatley Peters. Phillis Wheatley was the first African American woman to publish a collection of poetry in America in 1773, and this timely anthology celebrates the 250th anniversary of her extraordinary poetry collection, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, by inviting 20 Black female poets to reimagine the work of this iconic literary ancestor in original poems meant for a new generation.

For the anthology, acclaimed and award-winning poets were asked to artistically interpret a Wheatley Peters poem and provide a brief craft essay or statement documenting their process for reinscribing the historical work. Each poet’s contribution consists of a brief essay, a new poem, and the original Wheatley poem that inspired the new work. This project was conceived by me and my co-editor to help make Wheatley Peters’s important work better known, and more accessible to the 21st-century lay reader. My passion for this project comes from experiencing first-hand students entering the university without ever having heard of, let alone studied, the work of this ground-breaking African American poet. This text is meant to open the way for educators at the high school and university level to teach Wheatley’s original work alongside contemporary poets re-imagining her poems and speaking critically on her importance in the 21st century.

ABW: Beyond my collection of essays Survivor’s Guilt: Essays on Race and American Identity, I am currently co-editor of an anthology with poet Danielle Legros Georges to be published before the new year, Wheatley at 250: Black Women Poets Re-Imagine the Verse of Phillis Wheatley Peters. Phillis Wheatley was the first African American woman to publish a collection of poetry in America in 1773, and this timely anthology celebrates the 250th anniversary of her extraordinary poetry collection, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, by inviting 20 Black female poets to reimagine the work of this iconic literary ancestor in original poems meant for a new generation.

For the anthology, acclaimed and award-winning poets were asked to artistically interpret a Wheatley Peters poem and provide a brief craft essay or statement documenting their process for reinscribing the historical work. Each poet’s contribution consists of a brief essay, a new poem, and the original Wheatley poem that inspired the new work. This project was conceived by me and my co-editor to help make Wheatley Peters’s important work better known, and more accessible to the 21st-century lay reader. My passion for this project comes from experiencing first-hand students entering the university without ever having heard of, let alone studied, the work of this ground-breaking African American poet. This text is meant to open the way for educators at the high school and university level to teach Wheatley’s original work alongside contemporary poets re-imagining her poems and speaking critically on her importance in the 21st century.

GM: There is a really compelling, human notion that spans across your work that what people really need to adopt in the face of bigotry is empathy. When we can see and understand the lives and hardships of others, and when we can have honest conversations about that, we can become kinder, better people. Do you find that your work as an educator and a writer is driven mostly by this notion, or are other, perhaps more dominant feelings, like anger or fear, sometimes more driving forces?

ABW: Anger is an emotion I do not often express in traditional ways. Anger has a debilitating effect on the body, and I work hard to move in a space of physical and intellectual peace. I am, however, motivated by what I experience in an often hostile world, and that motivation is the impetus for me to put pen to the page. Being an educator has certainly imbued in me a level of patience that might not come so easily in other professions. I regularly remind myself not to judge people based on what they know but to, instead, focus on how I can evolve their personal intellectual journey. People grow at different rates, so I just want students to walk away with some essential kernel that they can nurture as they continue to develop. That said, empathy comes out of relatability. Through stories I prove that the human condition is universal, and if you care about humanity, you need to make preserving it a lived practice whether someone looks like you or not.

ABW: Anger is an emotion I do not often express in traditional ways. Anger has a debilitating effect on the body, and I work hard to move in a space of physical and intellectual peace. I am, however, motivated by what I experience in an often hostile world, and that motivation is the impetus for me to put pen to the page. Being an educator has certainly imbued in me a level of patience that might not come so easily in other professions. I regularly remind myself not to judge people based on what they know but to, instead, focus on how I can evolve their personal intellectual journey. People grow at different rates, so I just want students to walk away with some essential kernel that they can nurture as they continue to develop. That said, empathy comes out of relatability. Through stories I prove that the human condition is universal, and if you care about humanity, you need to make preserving it a lived practice whether someone looks like you or not.

Read more about White’s work on her website: http://www.artressbethanywhite.com/

Follow her on Twitter/X: @ArtressWhite

or on Instagram: @ArtressWhite

Follow her on Twitter/X: @ArtressWhite

or on Instagram: @ArtressWhite