INTERVIEW

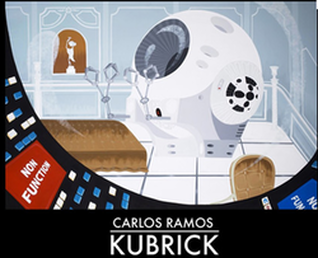

The Scrapbook You Don't Remember Making: AN INTERVIEW WITH aRTIST cARLOS rAMOS

by mANDA fREDERICK

2012

What possibly strikes a viewer first about Carlos Ramos' work is that the images have a sense of familiarity - but not familiar like, say, a Van Gogh print that you've seen all your life on a postcard or a refrigerator magnet. When you view Ramos' paintings inspired by David Bowie and Stanley Kubrick, you don't think, “I've seen this before.” Because, of course, you have not seen Ramos' paintings before. But you think: “I somehow know this. I have experienced this.” Because Ramos' work distills the vivid, real-life personas of Bowie that we know and the narratives of Kubrick's films that we've watched, his paintings ask viewers to call up a string of concrete, sensual memories and experiences related to the content: that Greyhound bus ride to Seattle listening to “Rock 'n' Roll Suicide” from The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust on repeat, waiting for the moment when the music cuts out and Bowie sings that we're not alone; that Comp II visual analysis paper your student wrote on the use of sound and color in The Shining; that summer you spent, as a child, at your uncle's house in the Michigan country-side, watching and re-watching The Labyrinth. Glancing through Ramos' work is like flipping through a scrapbook you don't remember making.

This experiential reaction from the viewer is one of Ramos' favorite aspects of creating and sharing these images. Ramos expresses, “The best part of the Kubrick show was everyone wanting to tell me a personal story about Kubrick and how he affected their lives. I've heard more stories than I can remember.”

In the interview that follows, Ramos shares his thoughts on art in this new media age, the creation of his work, and the effect he hopes to have on his viewers.

This experiential reaction from the viewer is one of Ramos' favorite aspects of creating and sharing these images. Ramos expresses, “The best part of the Kubrick show was everyone wanting to tell me a personal story about Kubrick and how he affected their lives. I've heard more stories than I can remember.”

In the interview that follows, Ramos shares his thoughts on art in this new media age, the creation of his work, and the effect he hopes to have on his viewers.

Manda Frederick: Glassworks is attracted to your work because it encompasses the energy of “new media”--the representation of narrative or information through image and a sense of motion. But “new media” is, of course, hard to define absolutely. What does “new media” mean to you as an artist or consumer of art, and what do you think its place is in the current landscape of art?

Carlos Ramos: I feel that "new media" is just a term that means more people can share their ideas globally. Tumblr, I feel, is the best example in that it's almost anonymous, unlike Facebook, but people from every part of the world share not only themselves but, more importantly, their tastes. It's an image-based site, mostly, but can also service writing or any other obsession. I only post art in it a couple times a week and tend not to follow artists but rather people who share the same tastes as me. How is this marketable? I don't think anybody knows yet, but this sharing of ideas and taste has been a breakthrough for me as a form of entertainment. For example, I have a tumblr page where all I do is caricatures of Howard Stern characters.

As far as being an artist, I love having something like this aside from just having an art website. It allows people who like my stuff to follow me and hopefully get an inside look into my influences because, as you can see in my art, I'm more pushed by imagery from film and music than I am by fine art.

As far as being an artist, I love having something like this aside from just having an art website. It allows people who like my stuff to follow me and hopefully get an inside look into my influences because, as you can see in my art, I'm more pushed by imagery from film and music than I am by fine art.

MF: While Glassworks is featuring your paintings, you are also the creator of the animated series The X's for Nickelodeon. Can you reflect a little bit on the differences for you, as an artist, in creating still-frame paintings versus an animated series?

CR: With both fine art and animation of an expert level, you are dealing with art as commerce. So with both things you are trying to satisfy your own tastes and, at the same time, a wider audience. With an animated series, you are in charge of a small army of people who are all trying to get your vision to the screen. It's an incredible job that can be extremely rewarding, but it can also be exhausting to be a boss. Fine art is the opposite: you are locked-up inside for years talking to your dog. Animation and painting are totally different experiences but both come with their own down sides and set politics, for sure.

MF: It seems art has traditionally been thought to have an element of “social responsibility,” to act as a representation of the time and culture in which it is created. But “art,” in this technological and new-media age, seems to be changing in how it is created and consumed. Do you think that traditional expectation of art is still true?

CR: Well, to be honest, the market is flooded with every kind of art these days (my e-mail inbox is filled with group art-show requests ranging from interesting to absurd) and "social responsibility" is a term to be held to politicians and police. Art is in the hands of an individual who shouldn't have to think about being "responsible." An artist doesn't sit back and go, "What's in the news today…?" An artist creates from their gut and tries to push through, in an image of something personal, and then place it on a wall. After that, it's up to the viewer to be moved or just to call it crap.

MF: It occurs to me, then, that the publishing industry and writing itself is, of course, also changing with technological advances, and many writers lament on the “death of books” and “literacy” because of this digital age in which we live. The technological era could be—maybe should be—having the same effect on art, such as paintings. And, yet, I have not encountered the same sort of sadness or sense of finality from visual artists. Do you feel that this technological era is harming how people consumer art, or harming the quality of people's understanding of what “good” art is?

CR: Yes and no is the clearest answer. Technological advances, especially the internet, have made art collectors out of everyone. And there's a lot of art out there meeting the demand for people wanting to have art on their walls, desktops, iPad cases etc. So the term "good art" is becoming looser because something very low brow can appeal to somebody living in France who wants that image on their backpack. I may not agree with all of it, but it is nice to see so much excitement about art.

I get daily requests for prints, which I don't do. Maybe because I don't hang prints in my own place. I want the real thing. A real piece of art feeds me daily. Looking at a real brush line or a mistake on the canvas delights me, and I just don't get that charge from a print. I remember the first time I saw a real Van Gough. It blew me away because postcards and books can never do his work justice. It's a textural experience. I guess my point is for my own personal taste I don't want "art" on my jeans. Plus, the idea of going to the post office weekly with a car full of my prints in tubes and printed iPod cases in boxes scared the hell out of me.

CR: With both fine art and animation of an expert level, you are dealing with art as commerce. So with both things you are trying to satisfy your own tastes and, at the same time, a wider audience. With an animated series, you are in charge of a small army of people who are all trying to get your vision to the screen. It's an incredible job that can be extremely rewarding, but it can also be exhausting to be a boss. Fine art is the opposite: you are locked-up inside for years talking to your dog. Animation and painting are totally different experiences but both come with their own down sides and set politics, for sure.

MF: It seems art has traditionally been thought to have an element of “social responsibility,” to act as a representation of the time and culture in which it is created. But “art,” in this technological and new-media age, seems to be changing in how it is created and consumed. Do you think that traditional expectation of art is still true?

CR: Well, to be honest, the market is flooded with every kind of art these days (my e-mail inbox is filled with group art-show requests ranging from interesting to absurd) and "social responsibility" is a term to be held to politicians and police. Art is in the hands of an individual who shouldn't have to think about being "responsible." An artist doesn't sit back and go, "What's in the news today…?" An artist creates from their gut and tries to push through, in an image of something personal, and then place it on a wall. After that, it's up to the viewer to be moved or just to call it crap.

MF: It occurs to me, then, that the publishing industry and writing itself is, of course, also changing with technological advances, and many writers lament on the “death of books” and “literacy” because of this digital age in which we live. The technological era could be—maybe should be—having the same effect on art, such as paintings. And, yet, I have not encountered the same sort of sadness or sense of finality from visual artists. Do you feel that this technological era is harming how people consumer art, or harming the quality of people's understanding of what “good” art is?

CR: Yes and no is the clearest answer. Technological advances, especially the internet, have made art collectors out of everyone. And there's a lot of art out there meeting the demand for people wanting to have art on their walls, desktops, iPad cases etc. So the term "good art" is becoming looser because something very low brow can appeal to somebody living in France who wants that image on their backpack. I may not agree with all of it, but it is nice to see so much excitement about art.

I get daily requests for prints, which I don't do. Maybe because I don't hang prints in my own place. I want the real thing. A real piece of art feeds me daily. Looking at a real brush line or a mistake on the canvas delights me, and I just don't get that charge from a print. I remember the first time I saw a real Van Gough. It blew me away because postcards and books can never do his work justice. It's a textural experience. I guess my point is for my own personal taste I don't want "art" on my jeans. Plus, the idea of going to the post office weekly with a car full of my prints in tubes and printed iPod cases in boxes scared the hell out of me.

MF: Your work strikes me as sort of updated “ekphrastic” work—art in response to other art. In this case, Bowie and Kubrick. Traditional ekphrasis tended to mean writing something in response to visual work. In your work, you create an image in response to other images or visual work. Can you speak to how these visual artists influence your art?

CR: Both the Bowie and Kubrick shows just came from my own personal desire. Kubrick is my own obsession and so it was a show I wanted to commit to and see to the end. Bowie was a quick follow-up, and it just tickled me to paint such a strong artist/musician with so many personas. Again, it would be hard to do any other rock star. There is only one Bowie just like there is only one Kubrick. So both those shows were just something I needed to get out of myself regardless of what anybody else wanted. Kubrick's work especially means so much to me, and spending over a year in his work was amazing. I wasn't out to "copy" anything but to celebrate his work because it is so specific and bold. But I will say that it ends with him because, after that show, people would ask which director I was going to do next—to me, there is no director like Kubrick or another director I could imagine spending that much of my time on.

CR: Both the Bowie and Kubrick shows just came from my own personal desire. Kubrick is my own obsession and so it was a show I wanted to commit to and see to the end. Bowie was a quick follow-up, and it just tickled me to paint such a strong artist/musician with so many personas. Again, it would be hard to do any other rock star. There is only one Bowie just like there is only one Kubrick. So both those shows were just something I needed to get out of myself regardless of what anybody else wanted. Kubrick's work especially means so much to me, and spending over a year in his work was amazing. I wasn't out to "copy" anything but to celebrate his work because it is so specific and bold. But I will say that it ends with him because, after that show, people would ask which director I was going to do next—to me, there is no director like Kubrick or another director I could imagine spending that much of my time on.

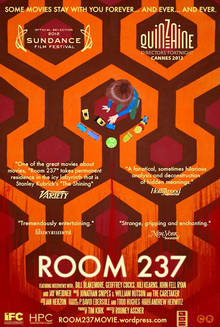

CR: The funny thing is that my Shining pieces led me to working with Rodney Ascher, the director of 'Room 237' a sort of documentary about people's obsession with The Shining. My Danny carpet image—“What’s in Room 237?”— was used as the poster, and I did a bit of animation on the film. It was accepted into Sundance and, now, Cannes. It was bought by IFC, tentatively coming out in the fall. It's just amazing to see my art come together with a film, being turned into another kind of art—all in celebration of the mighty Stanley Kubrick.

MF: Your paintings from Kubrick are obviously paintings. And, yet, when I survey online galleries that house your work, your paintings largely appear on new-media sites for film or science fiction. Why do you think that is? In creating your work, did you intend or hope to continue to align yourself with the cinema, or do you hope that your works stand alone as paintings in their own right?

CR: I don't know that there ever was a plan, to be honest. I pitched the show to Copro Gallery, and I think they let me do it just because I was so excited and clearly was going to do it anyway. But as the show got closer to opening’ I was being interviewed by as many film sites as art sites, which was very exciting and unexpected—although my past my work has had a fan-base in the genres of film and video games.

But also the best part of the Kubrick show was everyone wanting to tell me a personal story about Kubrick and how he affected their lives. I've heard more stories than I can remember. One of my favorite Kubrick nuts is Pixar's Lee Unkrich who payed for most of the Kickstarter on Room 237. He knows more about The Shining than anybody. I hope he writes a book.

MF: Your paintings from Kubrick are obviously paintings. And, yet, when I survey online galleries that house your work, your paintings largely appear on new-media sites for film or science fiction. Why do you think that is? In creating your work, did you intend or hope to continue to align yourself with the cinema, or do you hope that your works stand alone as paintings in their own right?

CR: I don't know that there ever was a plan, to be honest. I pitched the show to Copro Gallery, and I think they let me do it just because I was so excited and clearly was going to do it anyway. But as the show got closer to opening’ I was being interviewed by as many film sites as art sites, which was very exciting and unexpected—although my past my work has had a fan-base in the genres of film and video games.

But also the best part of the Kubrick show was everyone wanting to tell me a personal story about Kubrick and how he affected their lives. I've heard more stories than I can remember. One of my favorite Kubrick nuts is Pixar's Lee Unkrich who payed for most of the Kickstarter on Room 237. He knows more about The Shining than anybody. I hope he writes a book.

MF: Could you talk a little bit, more specifically, about one of your Kubrick images?

CR: Well, “Forever and Ever” is obviously portraying an extremely iconic Shining image of the twins in the hallway. So, clearly, it had to go in my Kubrick show, but how to paint it? I rely heavily on getting an image to "pop" into my head. A vision. And this one I think took awhile. Then the image was there, and I went for it. The problem with this piece is that it had to be completely symmetrical, and it contained specific patterns like the wall paper. So this piece took a lot of pre-planning and stencils, which I hate. And maybe I didn't have as much fun with this painting but, after, I really liked it. I have a very consistent habit of hating a piece until it's done, and then I don't look at it for a week. Then they usually surprise me. It's an odd process.

But I don’t know if there is much of a definite method to my painting. Unlike a lot of painters, I don't plan much. I don't project a sketch onto the canvas. It's all pretty much free-hand on the canvas, which is the way I like to work. So although there is a pre-existing image for my Kubrick or Bowie paintings, I'm still just wrestling with a giant piece of wood, and I don't know how it will end—even in painting something as specific as a Kubrick image. That's the joy (and pain) for me. Not knowing where I'm going with a piece. It's a very rewarding process.

CR: Well, “Forever and Ever” is obviously portraying an extremely iconic Shining image of the twins in the hallway. So, clearly, it had to go in my Kubrick show, but how to paint it? I rely heavily on getting an image to "pop" into my head. A vision. And this one I think took awhile. Then the image was there, and I went for it. The problem with this piece is that it had to be completely symmetrical, and it contained specific patterns like the wall paper. So this piece took a lot of pre-planning and stencils, which I hate. And maybe I didn't have as much fun with this painting but, after, I really liked it. I have a very consistent habit of hating a piece until it's done, and then I don't look at it for a week. Then they usually surprise me. It's an odd process.

But I don’t know if there is much of a definite method to my painting. Unlike a lot of painters, I don't plan much. I don't project a sketch onto the canvas. It's all pretty much free-hand on the canvas, which is the way I like to work. So although there is a pre-existing image for my Kubrick or Bowie paintings, I'm still just wrestling with a giant piece of wood, and I don't know how it will end—even in painting something as specific as a Kubrick image. That's the joy (and pain) for me. Not knowing where I'm going with a piece. It's a very rewarding process.

To see more of Ramos: www.theCarlosRamos.com