Interview

hAPPILY eVER aFTER: AN INTERVIEW WITH Christopher Dewan

BY ERIC AVEDISSIAN, Jordan Moslowski, & Emily strauser

OCTOBER 2017

Once upon a time, fairy tales delivered heroes into their happily ever afters, but what happens when “happily ever after” ends and reality sets in?

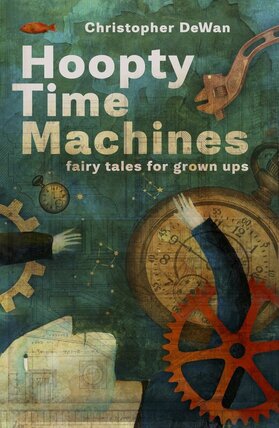

In his latest book, self described storyteller Christopher DeWan presents the fairy tale genre in a new light. Hoopty Time Machines: fairy tales for grown ups is a collection of short stories that explore what happens “after happily ever after,” incorporating some of the darkness that comes from the original fairy tales. By flipping the roles around—turning the scariest of monsters into heroes, and breaking our favorite heroes from their cookie-cutter molds—he brings fairy tales back to reality, where things are not always so black and white.

Through a series of short stories that combines naive fantasy with sobering reality, DeWan forces us to consider why so many of us wish to change aspects of our lives in order to achieve what we think we want most and to rethink the true meaning of our happy endings.

In his latest book, self described storyteller Christopher DeWan presents the fairy tale genre in a new light. Hoopty Time Machines: fairy tales for grown ups is a collection of short stories that explore what happens “after happily ever after,” incorporating some of the darkness that comes from the original fairy tales. By flipping the roles around—turning the scariest of monsters into heroes, and breaking our favorite heroes from their cookie-cutter molds—he brings fairy tales back to reality, where things are not always so black and white.

Through a series of short stories that combines naive fantasy with sobering reality, DeWan forces us to consider why so many of us wish to change aspects of our lives in order to achieve what we think we want most and to rethink the true meaning of our happy endings.

Glassworks Magazine (GM): We’ve all mostly grown up with the same sorts of fairy tales: Cinderella, Snow White, Hansel and Gretel, and many others that remain classical tales and staples in childhood reading. Now as adults, why do you think we need to have a new classification of what constitutes a fairy tale?

Christopher DeWan (CD): Fairy tales have always been dark, scary things, full of so much murder and rape and incest and eyes getting pecked out and people getting ripped in half. They’re really terrible—terribly frightening things. But I agree that, for many of us, the Disney versions of the stories have eclipsed some of the deeper, more substantial content of the original stories.

I never set out to create a “new” classification of fairy tales, but I did want to use my book’s subtitle (“fairy tales for grown ups”) to flag this for readers: these stories aren’t meant to be sweet or safe. They’re meant to unsettle and to scratch away at easy notions of “happily ever after.”

Christopher DeWan (CD): Fairy tales have always been dark, scary things, full of so much murder and rape and incest and eyes getting pecked out and people getting ripped in half. They’re really terrible—terribly frightening things. But I agree that, for many of us, the Disney versions of the stories have eclipsed some of the deeper, more substantial content of the original stories.

I never set out to create a “new” classification of fairy tales, but I did want to use my book’s subtitle (“fairy tales for grown ups”) to flag this for readers: these stories aren’t meant to be sweet or safe. They’re meant to unsettle and to scratch away at easy notions of “happily ever after.”

GM: By taking commonly known Disney fairy tales and making them more cynical, do you think you’ve given the fairy tale back it’s moral meaning in some way, or created something else entirely?

CD: My intention was to lean on some of the familiar tropes of fairy tales, myths, pop culture—a whole slew of our shared cultural vocabulary—and then play it out: Where do these familiar stories go once they’re inhabited by contemporary psychologies? But I hope these stories aren’t cynical. I wanted to be very compassionate toward these characters—characters who have, for the most part, been sold a bill of goods (“Happily ever after”), and now the rust is starting to show and the warranty is expired and they have a moment of “What now?” I wanted to explore the minds of these characters in a moment after happily ever after.

CD: My intention was to lean on some of the familiar tropes of fairy tales, myths, pop culture—a whole slew of our shared cultural vocabulary—and then play it out: Where do these familiar stories go once they’re inhabited by contemporary psychologies? But I hope these stories aren’t cynical. I wanted to be very compassionate toward these characters—characters who have, for the most part, been sold a bill of goods (“Happily ever after”), and now the rust is starting to show and the warranty is expired and they have a moment of “What now?” I wanted to explore the minds of these characters in a moment after happily ever after.

GM: Fairy tales usually include some type of wish fulfillment: a princess wants to marry a handsome prince or a peasant boy wants riches and fame; everybody wants something. If these things are still true in adult fairy tales, what do you think creates the divide between the two groups’ version of a fairy tale?

CD: I think most stories are about wish fulfillment, really: a character goes on a journey in search of a better life, and then, by the end of the story, they’ve either made progress toward that or they haven’t. In the stories we tell children, we’re often content to make the end of the story simple—but adults generally know better.

Endings aren’t simple. Sometimes we get exactly what we want, only to discover that it doesn’t actually make us happier; our wish comes true but it doesn’t save us the ways we might’ve imagined. Maybe that’s what adulthood is: the realization that happiness comes slowly and incrementally rather than through the sudden granting of a big wish. When happiness comes, it’s slow and steady and probably requires adjusting one’s perspective.

CD: I think most stories are about wish fulfillment, really: a character goes on a journey in search of a better life, and then, by the end of the story, they’ve either made progress toward that or they haven’t. In the stories we tell children, we’re often content to make the end of the story simple—but adults generally know better.

Endings aren’t simple. Sometimes we get exactly what we want, only to discover that it doesn’t actually make us happier; our wish comes true but it doesn’t save us the ways we might’ve imagined. Maybe that’s what adulthood is: the realization that happiness comes slowly and incrementally rather than through the sudden granting of a big wish. When happiness comes, it’s slow and steady and probably requires adjusting one’s perspective.

"Endings aren't simple. Sometimes we get exactly what we want, only to discover that it doesn't actually make us happier."

GM: Your title story, “Hoopty Time Machine,” is about a father who puts all of his time into creating a time machine out of a car in the driveway. The narrator claims that his dad is really “trying to correct all of his past mistakes” which he uses to escape his life and, by extension, his family. Modern society tells us that we want to be married with kids. Why, even after we have achieved that, are we unsatisfied?

CD: I should say, I'm not married and I don't have kids, and the joke's on me if those two things really would solve all of my life's troubles. Marriage and kids offer the chance to start measuring success based on something other than our own self-satisfaction—to start thinking of our life's accomplishments on a timeline that's longer than our own life.

I don't think the problem is "marriage" or "kids." The problem is the mythological ideas we build up around marriage and kids. Like everything else in life, the real version of “marriage” and “kids” live up to those built-up mythologies: if you’re relying on marriage and kids to save you, then in the end, you’re right where you started, emotionally, but now you’re also married with kids. You’re solving an inner problem with an external trapping, and it generally isn’t going to work.

GM: You’ve mentioned that many of your characters find their happy endings through their escape from reality. What about today’s society do you think we need escaping from?

CD: A story about a wish is the story of a person who is discontent in their situation: they believe their life isn’t good, but also they believe that if they could change one thing, then their life would be good. This isn’t a uniquely American idea, but it’s an idea that runs very very deep in present-day consumerist America: “My life right now is incomplete, but if only I buy a new blender or a new computer or a new car, then I’ll arrive.” “If I only change this one thing, then I’ll finally be happy…”

The characters in my stories generally believe that if they can trade their current situation for a different one, then their lives will be fixed—and that belief is specious. They don’t need to escape from reality; they need to figure out that their way of thinking is keeping them from living in reality. Some of the characters figure this out better than others.

GM: Your collection begins with a family who drives off in search of the American Dream and ends with the story entitled “American Dream.” Do you feel that your collection is ordered in a way that allows this journey to flow from the hopes of finding the American Dream to realizing it may not exist?

CD: Thanks for asking! This was one of the joys of putting this together as a book. One reviewer called the book a “perfect mix tape” and that made me so happy, because I really did want to create a journey for a reader who tracks through from beginning to end. Obviously there’s nothing that forces people to read it in order, but the order is very intentional. Bookending with the two “American Dream” stories is very intentional—the first one is searching for it and the second one is really finding it in an unexpected way.

There are also “Easter eggs” hidden in the collection—recurring characters and themes and images, stories that riff on prior stories—and I imagine that’s more fun for a reader who reads the book in order. Goldilocks is in a couple stories, and so is a little boy named Max. Sleeping Beauty is hiding in one of the stories. There are others.

CD: I should say, I'm not married and I don't have kids, and the joke's on me if those two things really would solve all of my life's troubles. Marriage and kids offer the chance to start measuring success based on something other than our own self-satisfaction—to start thinking of our life's accomplishments on a timeline that's longer than our own life.

I don't think the problem is "marriage" or "kids." The problem is the mythological ideas we build up around marriage and kids. Like everything else in life, the real version of “marriage” and “kids” live up to those built-up mythologies: if you’re relying on marriage and kids to save you, then in the end, you’re right where you started, emotionally, but now you’re also married with kids. You’re solving an inner problem with an external trapping, and it generally isn’t going to work.

GM: You’ve mentioned that many of your characters find their happy endings through their escape from reality. What about today’s society do you think we need escaping from?

CD: A story about a wish is the story of a person who is discontent in their situation: they believe their life isn’t good, but also they believe that if they could change one thing, then their life would be good. This isn’t a uniquely American idea, but it’s an idea that runs very very deep in present-day consumerist America: “My life right now is incomplete, but if only I buy a new blender or a new computer or a new car, then I’ll arrive.” “If I only change this one thing, then I’ll finally be happy…”

The characters in my stories generally believe that if they can trade their current situation for a different one, then their lives will be fixed—and that belief is specious. They don’t need to escape from reality; they need to figure out that their way of thinking is keeping them from living in reality. Some of the characters figure this out better than others.

GM: Your collection begins with a family who drives off in search of the American Dream and ends with the story entitled “American Dream.” Do you feel that your collection is ordered in a way that allows this journey to flow from the hopes of finding the American Dream to realizing it may not exist?

CD: Thanks for asking! This was one of the joys of putting this together as a book. One reviewer called the book a “perfect mix tape” and that made me so happy, because I really did want to create a journey for a reader who tracks through from beginning to end. Obviously there’s nothing that forces people to read it in order, but the order is very intentional. Bookending with the two “American Dream” stories is very intentional—the first one is searching for it and the second one is really finding it in an unexpected way.

There are also “Easter eggs” hidden in the collection—recurring characters and themes and images, stories that riff on prior stories—and I imagine that’s more fun for a reader who reads the book in order. Goldilocks is in a couple stories, and so is a little boy named Max. Sleeping Beauty is hiding in one of the stories. There are others.

"A story about a wish is the story of a person who is discontent in their situation... they believe that if they could change one thing, then their life would be good."

GM: A lot of your stories end up being sympathetic to the monsters of stories we as kids were always taught to fear. What do you think you’ve accomplished in taking characters that are typically bad and flat and turn them into more round or dynamic characters?

CD: I think a lot of those old fairy tales get more interesting once we set aside the idea of “good guys and bad guys.” When I read classic fairy tales, the heroes usually behave abominably: they trespass, steal, lie, murder—usually just because of their fear of an “other.”

I remember years ago reading John Gardner’s Grendel: I love how this story makes me love the monster. It makes me love the monster without even needing to strip him of his monstrosity. In contrast to Grendel, Beowulf winds up looking like an egomaniacal asshole—and I’d bet that’s true for a lot of the fairy tales and myths we’re raised on.

Flipping it lets us read the original story more holistically, and that’s one thing I tried to do in HOOPTY TIME MACHINES: The heroes who seek fortune and glory by killing a monster are egomaniacal assholes. Superman means well, but he’s kind of an egomaniacal asshole. Poseidon is absolutely an egomaniacal asshole. Meanwhile, Godzilla and the Bogeyman and the trolls have gotten a bad rap; on closer inspection, they’re not so bad.

GM: Since you have turned monsters into your protagonists in some of your stories, who does this leave behind to fulfill the role of the antagonist or “monster” in these stories?

CD: The book is getting called “domestic fabulism,” which is a relatively new label for certain kinds of speculative fiction or magic realism or whatever you want to call it. But my favorite stories in the collection are actually about ambiguity—how something might seem magic or not mainly based on the assumptions of the person who’s doing the seeing: Is that dad actually building a time machine? Is the teen girl actually practicing voodoo? Does that atheist woman really have stigmata? Have that man’s parents really been replaced by trolls?

It’s in a story’s moment of not knowing that I feel my pulse quicken. That’s the moment where I see that, despite everything I think I know, the world might not operate the way I think it does—that there might still be mysteries left, mysteries which, for lack of a better explanation, we’ll call “magic.” The monster is whatever lurks under the bed and reminds us this—reminds us that we don’t actually understand the nature of the universe. The real goal of fairy tales, I think, and maybe stories in general, is to remind us of this feeling of wonder, to remind us that the world is wonderful and can truly never be resolved.

CD: I think a lot of those old fairy tales get more interesting once we set aside the idea of “good guys and bad guys.” When I read classic fairy tales, the heroes usually behave abominably: they trespass, steal, lie, murder—usually just because of their fear of an “other.”

I remember years ago reading John Gardner’s Grendel: I love how this story makes me love the monster. It makes me love the monster without even needing to strip him of his monstrosity. In contrast to Grendel, Beowulf winds up looking like an egomaniacal asshole—and I’d bet that’s true for a lot of the fairy tales and myths we’re raised on.

Flipping it lets us read the original story more holistically, and that’s one thing I tried to do in HOOPTY TIME MACHINES: The heroes who seek fortune and glory by killing a monster are egomaniacal assholes. Superman means well, but he’s kind of an egomaniacal asshole. Poseidon is absolutely an egomaniacal asshole. Meanwhile, Godzilla and the Bogeyman and the trolls have gotten a bad rap; on closer inspection, they’re not so bad.

GM: Since you have turned monsters into your protagonists in some of your stories, who does this leave behind to fulfill the role of the antagonist or “monster” in these stories?

CD: The book is getting called “domestic fabulism,” which is a relatively new label for certain kinds of speculative fiction or magic realism or whatever you want to call it. But my favorite stories in the collection are actually about ambiguity—how something might seem magic or not mainly based on the assumptions of the person who’s doing the seeing: Is that dad actually building a time machine? Is the teen girl actually practicing voodoo? Does that atheist woman really have stigmata? Have that man’s parents really been replaced by trolls?

It’s in a story’s moment of not knowing that I feel my pulse quicken. That’s the moment where I see that, despite everything I think I know, the world might not operate the way I think it does—that there might still be mysteries left, mysteries which, for lack of a better explanation, we’ll call “magic.” The monster is whatever lurks under the bed and reminds us this—reminds us that we don’t actually understand the nature of the universe. The real goal of fairy tales, I think, and maybe stories in general, is to remind us of this feeling of wonder, to remind us that the world is wonderful and can truly never be resolved.

Find out more about Christopher DeWan on his website: http://christopherdewan.com/