Interview

Embracing Self-Love and Creativity as a Storyteller: AN INTERVIEW WITH Danny Tayara

BY Lesley George, Bryce Morris, and Shea Roberts

October 2023

Danny Tayara (they/he/she) is a queer, mixed-race filmmaker, writer, and illustrator from Seattle, Washington. They are an active supporter of several movements: gay rights, climate action, and Black Lives Matter, to name a few. After working professionally as Festival Director for the Seattle Queer Film Festival until 2018, they received their B.A. in Film Studies from Seattle University in 2020, where they focused heavily on scientific film, data visualization, and XR (extended reality). Outside of filmmaking, they are currently a Production & UX Research Director (user experience) at VR Ulysses, a startup company in Seattle building a VR app for network security and network operations.

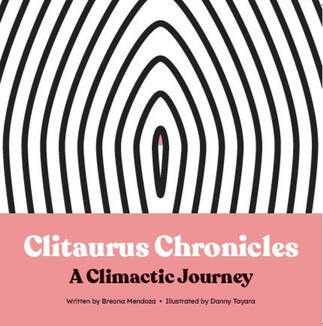

Tayara’s most recent publication, Clitaurus Chronicles, is a sex-education book about a “clitaurus” named Clitty who is writing a novel but can’t figure out what the climax should be. As Danny has the unique perspective of someone in both the STEM field and the world of storytellers, Glassworks was fortunate to ask them about their experiences. In this interview, Danny discusses what queerness and sexual liberation mean to them within a highly competitive industry.

Tayara’s most recent publication, Clitaurus Chronicles, is a sex-education book about a “clitaurus” named Clitty who is writing a novel but can’t figure out what the climax should be. As Danny has the unique perspective of someone in both the STEM field and the world of storytellers, Glassworks was fortunate to ask them about their experiences. In this interview, Danny discusses what queerness and sexual liberation mean to them within a highly competitive industry.

Glassworks Magazine (GM): What drew you towards illustrating Clitaurus Chronicles after having established yourself as a filmmaker? How was illustration different from your style of film production, and was it worth trying?

Danny Tayara (DT): I met Breona Mendoza, the author of Clitaurus Chronicles, when I volunteered at a camp for LGBTQ+ teens. A few years ago she was asking around to see if she knew anyone who might be able to illustrate a book she had written. I mentioned I had already drawn a cover of a children's book previously, and I was interested in exploring book illustration more. Otherwise, up until that point I had only illustrated digital content.

My illustrations in Clitaurus Chronicles were different from my style of film production mainly in that they were aimed at a younger audience than my films are. Breona and I grappled for a long time to arrive at the best visual style for the illustrations, because even slight differences in things like line width or color palette, for example, made the book seem too baby-ish or too adult. My films are typically made for people my age and with my shared interests, so the visual approach is somewhat more unconventional.

GM: For both you and Breona, the publication of a book of this kind was a first, despite your having written and published research essays previously. What was collaborating with Breona like, especially considering your overlapping experiences with activism, the queer community, and sex positivity? Did the process of illustrating and publishing feel similar to working with people on a film, or was it an adjustment?

DT: Having volunteered with Breona at an LGBTQ+ summer camp, I was familiar with her politics, and I knew we were already on the same page in that way. Illustrating and publishing a book for the first time—particularly one that doesn't fit into a pre-made mold—was a big challenge for both of us. But we are both intimately familiar with the process of executing concepts nobody had ever heard of before. Even though the technical workflow was different than that of filmmaking, the anxieties were still the same in regard to whether or not we would reach audiences as intended.

Danny Tayara (DT): I met Breona Mendoza, the author of Clitaurus Chronicles, when I volunteered at a camp for LGBTQ+ teens. A few years ago she was asking around to see if she knew anyone who might be able to illustrate a book she had written. I mentioned I had already drawn a cover of a children's book previously, and I was interested in exploring book illustration more. Otherwise, up until that point I had only illustrated digital content.

My illustrations in Clitaurus Chronicles were different from my style of film production mainly in that they were aimed at a younger audience than my films are. Breona and I grappled for a long time to arrive at the best visual style for the illustrations, because even slight differences in things like line width or color palette, for example, made the book seem too baby-ish or too adult. My films are typically made for people my age and with my shared interests, so the visual approach is somewhat more unconventional.

GM: For both you and Breona, the publication of a book of this kind was a first, despite your having written and published research essays previously. What was collaborating with Breona like, especially considering your overlapping experiences with activism, the queer community, and sex positivity? Did the process of illustrating and publishing feel similar to working with people on a film, or was it an adjustment?

DT: Having volunteered with Breona at an LGBTQ+ summer camp, I was familiar with her politics, and I knew we were already on the same page in that way. Illustrating and publishing a book for the first time—particularly one that doesn't fit into a pre-made mold—was a big challenge for both of us. But we are both intimately familiar with the process of executing concepts nobody had ever heard of before. Even though the technical workflow was different than that of filmmaking, the anxieties were still the same in regard to whether or not we would reach audiences as intended.

"Illustrating and publishing a book for the first time—particularly one that doesn't fit into a pre-made mold—was a big challenge for both of us."

GM: We noticed that sex positivity is a recurring theme in your work, looking at examples like Pizza Roles, You’ve Got Tail, and now Clitaurus Chronicles—why is that topic so important for you to discuss? What does it mean to you, and how does it connect to what you want people to take away from Clitaurus Chronicles?

DT: From a young age, I've been acutely aware of media's impact on queer youth. I hardly ever saw myself on screen as a kid, and when I did, it wasn't until I experienced the Seattle Queer Film Festival. I ended up working for that festival for seven years, so I spent a lot of time watching and talking about queer film. I sometimes joke that I was paid to watch porn at that job (which was sometimes true).

Through the queer film world, I got wind of the HUMP! Film Festival, which is an amateur porn festival. Seattle is very fond of it. I was encouraged to make films and submit them to HUMP!, which I did, and since then I've become even more relaxed around the subject of sex. I used to be afraid to talk about sex or sexuality at all, and now it's just a normal, everyday occurrence. Over time, I learned from my community that shame feeds on silence. If we're going to talk about queer sexuality at all, we have to learn how to be comfortable talking about sex first.

Clitaurus Chronicles is a non-threatening, approachable way to start that conversation. My mom hardly ever mentions sex, and we don't talk much about the book, but just the other day my partner overheard her reading the book aloud to her friends over the phone. That's exactly what I want this to do for people, particularly parents who never had access to quality sex education.

DT: From a young age, I've been acutely aware of media's impact on queer youth. I hardly ever saw myself on screen as a kid, and when I did, it wasn't until I experienced the Seattle Queer Film Festival. I ended up working for that festival for seven years, so I spent a lot of time watching and talking about queer film. I sometimes joke that I was paid to watch porn at that job (which was sometimes true).

Through the queer film world, I got wind of the HUMP! Film Festival, which is an amateur porn festival. Seattle is very fond of it. I was encouraged to make films and submit them to HUMP!, which I did, and since then I've become even more relaxed around the subject of sex. I used to be afraid to talk about sex or sexuality at all, and now it's just a normal, everyday occurrence. Over time, I learned from my community that shame feeds on silence. If we're going to talk about queer sexuality at all, we have to learn how to be comfortable talking about sex first.

Clitaurus Chronicles is a non-threatening, approachable way to start that conversation. My mom hardly ever mentions sex, and we don't talk much about the book, but just the other day my partner overheard her reading the book aloud to her friends over the phone. That's exactly what I want this to do for people, particularly parents who never had access to quality sex education.

|

GM: You mentioned the Seattle Queer Film Festival, which has a very similar name to your organization, the Seattle Queer Filmmakers, an organization focused on collaborating and sharing resources with other queer filmmakers—super helpful to upcoming creators! What made you decide to start Seattle Queer Filmmakers? How would you describe the process of that? Has being in SQF shaped your creative vision/process at all?

|

"Over time, I learned from my community that shame feeds on silence. If we're going to talk about queer sexuality at all, we have to learn how to be comfortable talking about sex first." |

DT: I started Seattle Queer Filmmakers because I wanted the group myself, honestly. There were a number of times when film gigs would come up, and I would want to send those opportunities to every queer filmmaker I knew. It became exhausting to use email and direct messages.

I also wanted to build community around queer people who make film, rather than just watch film. I started a Facebook group for SQF, and later on made a website to host profiles of each group member, so people outside the group could learn about each filmmaker and contact them for work if desired. It's a great resource when hiring for film projects, mine included. The group has many talented artists that I have called upon repeatedly.

I also wanted to build community around queer people who make film, rather than just watch film. I started a Facebook group for SQF, and later on made a website to host profiles of each group member, so people outside the group could learn about each filmmaker and contact them for work if desired. It's a great resource when hiring for film projects, mine included. The group has many talented artists that I have called upon repeatedly.

GM: How has your identity as a queer and mixed-race creator impacted you, both in the filmmaking industry and the STEM field? What advice would you offer someone as a result of your experiences?

DT: As a queer, mixed-race person, my identity and perspective necessitate critical analysis of any system that I experience. I see and experience friction in places a lot of people don't. This is largely what draws me to user experience (UX) design. Situations which used to cause me frustration (microaggressions, name change paperwork errors, and so on) now give me clearer ideas about how to approach my work as a UX designer/researcher. My advice: When we consider different perspectives, we make better designs.

GM: As a filmmaker, you already have experience in several genres (comedy, documentary, LGBTQ+, romance, short film) but are there any genres of film that you would like to experiment with in the future? Why have you chosen to explore what you have so far?

DT: I admire filmmakers who can write and edit comedy well, because I know how hard it is to do successfully. Writing comedy is difficult for me, so I would like more practice experimenting with it. I also foresee more documentaries in my future.

DT: As a queer, mixed-race person, my identity and perspective necessitate critical analysis of any system that I experience. I see and experience friction in places a lot of people don't. This is largely what draws me to user experience (UX) design. Situations which used to cause me frustration (microaggressions, name change paperwork errors, and so on) now give me clearer ideas about how to approach my work as a UX designer/researcher. My advice: When we consider different perspectives, we make better designs.

GM: As a filmmaker, you already have experience in several genres (comedy, documentary, LGBTQ+, romance, short film) but are there any genres of film that you would like to experiment with in the future? Why have you chosen to explore what you have so far?

DT: I admire filmmakers who can write and edit comedy well, because I know how hard it is to do successfully. Writing comedy is difficult for me, so I would like more practice experimenting with it. I also foresee more documentaries in my future.

"My advice: When we consider different perspectives, we make better designs."

GM: You have produced several short films and animations, such as Everyone Counts, While We’re Asleep, and The Curse. What is something you enjoy about filmmaking that you were not able to achieve as an illustrator? And vice-versa?

DT: Something I enjoy about filmmaking is being in a state of flow where, because I've been doing it so long, I'm no longer caught in the technical process, but rather can focus largely on story. As a book illustrator, it took me some time to learn the ropes of illustrating for print as opposed to digital art or animation, but one thing I really appreciated was not having to prepare all the individual assets for animation! In all seriousness though, there's something satisfying about making an actual, physical product. You can't see a film unless you're looking at a screen, so in some ways it doesn't feel like I have much to show for all the work I've done as a filmmaker, even though it was a LOT.

DT: Something I enjoy about filmmaking is being in a state of flow where, because I've been doing it so long, I'm no longer caught in the technical process, but rather can focus largely on story. As a book illustrator, it took me some time to learn the ropes of illustrating for print as opposed to digital art or animation, but one thing I really appreciated was not having to prepare all the individual assets for animation! In all seriousness though, there's something satisfying about making an actual, physical product. You can't see a film unless you're looking at a screen, so in some ways it doesn't feel like I have much to show for all the work I've done as a filmmaker, even though it was a LOT.

"The state of comedy at any point is a reflection on societal conventions, or in other words, what is acceptable and what isn't." |

GM: We noticed that Rejection and Other Happy Endings is an unreleased documentary—is there a specific reason for that? What about that piece feels different for you as compared to your other works?

DT: Rejection and Other Happy Endings is a personal documentary, so it feels different in that it's much more vulnerable than my other films, and I've encountered more frequent bouts of avoidance around finishing it. |

Beyond that, I originally took it on as a project in order to move through an emotional process for myself, which won't necessarily have a clear stopping point (although I do expect the film will in the coming years).

GM: Your short documentary, Oh, I Get It, speaks about queer people, people of color, women, and the marginalization they face in comedy. Generally, this marginalization is understood to be rampant elsewhere, such as in politics, education, STEM, and so on. What made you decide to address this issue in comedy, rather than anywhere else?

GM: Your short documentary, Oh, I Get It, speaks about queer people, people of color, women, and the marginalization they face in comedy. Generally, this marginalization is understood to be rampant elsewhere, such as in politics, education, STEM, and so on. What made you decide to address this issue in comedy, rather than anywhere else?

DT: The state of comedy at any point is a reflection on societal conventions, or in other words, what is acceptable and what isn't. Oh, I Get It may be a film about stand-up comedy, but it's certainly relevant politically, especially considering current discourse about what constitutes free speech. Aside from that, in the film industry it's often repeated that "what is most personal is most universal." Diving into a more contained personal story helps to make the content of the film relevant to the general public.