INTERVIEW

tHE sTATUS qUO IS THE eNEMY: AN INTERVIEW WITH dAVID gERROLD

BY jOSEPH bERENATO & kATLYN sLOUGH

2014

Science fiction writer David Gerrold created the fictional philosopher Solomon Short in the hostile world of the series The War Against the Chtorr, which, according to Gerrold, is “an extremely hostile universe. Nothing gets resolved. So it takes a lot more courage and commitment to be heroic.” But Solomon did survive and became a great man and philosopher, an inspiration to others and iconic both in his series and outside of it with sayings like, “You can lead a horse’s ass to water, but he’s still a horse’s ass.”

Gerrold, in a career that spans close to fifty years, has achieved great success in our hostile world: as an outspoken member of the LGBT community, he inspires other writers to fight for what they believe in. No matter the backlash, Gerrold stops at nothing to express his opinions, taking others to task both directly and indirectly through the adventures of famous characters. His writing alone often challenges the majority opinion, raising questions both from larger issues about gay rights, respect for others, and equality for everyone, and from small battles like overcoming poor self-image and what it means to create a family. He is the Solomon Short of real life—someone to help us through whatever oppositions stand in the way because he knows he can.

That isn’t mere hyperbole, either. Gerrold’s work has had a very real impact on individual readers, sometimes with incredible and inspiring results. “I will share this with you,” Gerrold said to us, “from time to time, I get a letter from someone thanking me because something I wrote helped them consider the option of adoption—or even more profound that one of my books (The Man Who Folded Himself) kept them from committing suicide when they realized they were gay. I think that’s probably the highest praise I could ever ask for.”

Glassworks approached David Gerrold regarding his role in the LGBT community and how he contributes to that role through his writing. He graciously responded with equally incredible and inspiring answers.

Gerrold, in a career that spans close to fifty years, has achieved great success in our hostile world: as an outspoken member of the LGBT community, he inspires other writers to fight for what they believe in. No matter the backlash, Gerrold stops at nothing to express his opinions, taking others to task both directly and indirectly through the adventures of famous characters. His writing alone often challenges the majority opinion, raising questions both from larger issues about gay rights, respect for others, and equality for everyone, and from small battles like overcoming poor self-image and what it means to create a family. He is the Solomon Short of real life—someone to help us through whatever oppositions stand in the way because he knows he can.

That isn’t mere hyperbole, either. Gerrold’s work has had a very real impact on individual readers, sometimes with incredible and inspiring results. “I will share this with you,” Gerrold said to us, “from time to time, I get a letter from someone thanking me because something I wrote helped them consider the option of adoption—or even more profound that one of my books (The Man Who Folded Himself) kept them from committing suicide when they realized they were gay. I think that’s probably the highest praise I could ever ask for.”

Glassworks approached David Gerrold regarding his role in the LGBT community and how he contributes to that role through his writing. He graciously responded with equally incredible and inspiring answers.

Glassworks Magazine (GM): Anyone can run a Google search on your name and get a superficial impression of David Gerrold: single father; liberal; gay; science-fiction writer. With many writers, though, to truly know them, one must read their work, where authors often share their innermost thoughts. Do you think this holds true for your work?

David Gerrold (DG): Yes and no. Yes, an author’s work reveals what he’s thinking about. And the subtext of the work reveals what he’s thinking about it. If you read enough books by a single author, you start to get an idea how his/her mind works. But those books are only what the author chooses to write, chooses to reveal. There are a lot of things I don’t write or haven’t yet written or won’t write. Some things would be misunderstood, some things are nobody else’s business, and some things can’t be written about at all, because they don’t translate well into words.

GM: That’s not often a sentiment you hear a prolific writer expressing. Assuming that you chose to translate your sentiments into words, which of your books should one read to really know you?

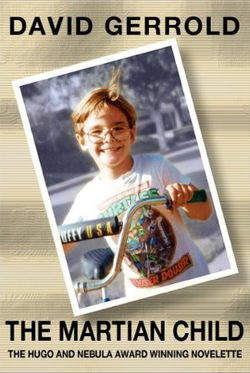

DG: My most revealing book is The Martian Child. It’s intentionally autobiographical. It’s about what the experience of adopting my son [Sean] and creating a family. It shows how both my heart and my mind work.

GM: The Martian Child was originally released as a novella and the sexual identity of the main character wasn’t disclosed. However, when you expanded the story into book form, the character, like his real-life counterpart, is gay. Why did you leave his orientation out of the novella?

DG: When I was writing the novella, I never thought that my sexual identity was part of the story. The story was about a father falling in love with his son. His being gay was irrelevant to that. When Tor Books wanted it expanded into a novel, the editor felt that I should include more detail about the [adoption] process and discuss the issue of a gay man adopting. The problem with that request was that there wasn’t that much to say. Being gay doesn’t disqualify you from adoption in California.

David Gerrold (DG): Yes and no. Yes, an author’s work reveals what he’s thinking about. And the subtext of the work reveals what he’s thinking about it. If you read enough books by a single author, you start to get an idea how his/her mind works. But those books are only what the author chooses to write, chooses to reveal. There are a lot of things I don’t write or haven’t yet written or won’t write. Some things would be misunderstood, some things are nobody else’s business, and some things can’t be written about at all, because they don’t translate well into words.

GM: That’s not often a sentiment you hear a prolific writer expressing. Assuming that you chose to translate your sentiments into words, which of your books should one read to really know you?

DG: My most revealing book is The Martian Child. It’s intentionally autobiographical. It’s about what the experience of adopting my son [Sean] and creating a family. It shows how both my heart and my mind work.

GM: The Martian Child was originally released as a novella and the sexual identity of the main character wasn’t disclosed. However, when you expanded the story into book form, the character, like his real-life counterpart, is gay. Why did you leave his orientation out of the novella?

DG: When I was writing the novella, I never thought that my sexual identity was part of the story. The story was about a father falling in love with his son. His being gay was irrelevant to that. When Tor Books wanted it expanded into a novel, the editor felt that I should include more detail about the [adoption] process and discuss the issue of a gay man adopting. The problem with that request was that there wasn’t that much to say. Being gay doesn’t disqualify you from adoption in California.

GM: Yet, you obviously found something to say on the topic.

DG: I did acknowledge being gay in the book, but I didn’t give it much attention, because I thought Sean was the more important story. I did report a couple of the conversations we’d had about my being gay, he accepted it and that was pretty much it. From my point of view, it was one of the least important parts of the adoption process. It was almost irrelevant to our relationship.

GM: But your editor felt it was necessary to include in the expanded novel?

DG: At the time, the anti-marriage forces were arguing that gay people could not be good parents and shouldn’t be allowed to adopt. They were making children the issue. Sean had been with me for a few years by then, and my reaction was, “You have it half-right. Yes, children are the issue. There are a lot of kids in the system who aren’t being adopted because there’s a critical shortage of qualified adoptive parents. Gay parents give those kids a chance at a real family.” But I didn’t want to write a polemic. I wanted to stay true to the theme of the original story, that my son and I were a family and just have that story stand as a simple refutation. Other gay adoptive parents have written more about their experiences because that’s where their attention was and I applaud them for it. That wasn’t the case here. I was more concerned with the needs of my son than making a political or social point. My son was my focus. The book was an afterthought.

GM: Is there anything else you have to reveal about parenting in relation to the needs of your son Sean?

DG: I think that the three lessons I learned from the entire process are so simple that we don’t realize how important they are.

The first is: Always take care of your own well-being. Kids look to their parents as the source of all well-being in the universe. If you don’t take care of your own well-being you have nothing to give to anyone else.

The second is: Never never never never never give up.

The third is: Never never never never never lose your sense of humor.

GM: You’re right. We often forget how important they are. These lessons obviously resonated with audiences; the book became popular enough to win several awards and be adapted by Seth Bass and Jonathan Tolins into the motion picture Martian Child. For this adaptation, though, the main character was changed from a gay single father to a straight widower.

DG: I don’t know whose decision it was to straight-wash the character. […]I wasn’t consulted about the changes. I did write some memos. I did make the novel available to them, but according to their public statements, they based their script entirely on the novella and never read the novel. It’s a weird assertion because so many plot points in the movie parallel plot points in the novel.

GM: How do you think the orientation change affected the story and its impact on your audience?

DG: I thought it weakened the picture. But that wasn’t the only part of the script that I felt was weak. In the novella and the novel, the hero does his research, he comes to the adoption well-prepared for the challenges. In the script, the hero seems totally inept at parenting—even worse, he makes some very un-adult decisions in how to deal with the boy.

In the movie, Dennis is portrayed as weird. In real life, Sean wasn’t weird. He was thoughtful, big-hearted, curious, and trusting. Yes, he had issues—and they were dramatic issues. Based on the evidence of the script, the screenwriters didn’t trust the source material and felt they had to add all kinds of weird stuff like sunglasses and weight belts and umbrellas. In my opinion, they missed the point — the story is about building a family and how father and son both discover their own humanity in the process.

[...]A key sequence in the novel is the “Pickled Mongoose” incident—where Sean learned how to tell jokes. That’s the moment that shows the first connection between father and son, the first time that the Martian child is learning how to be human. I think it’s the most important part of the story, because it’s the turning point in the relationship. That’s the sequence I want to see on the screen.

A lot of people were charmed by the movie and I’m glad they enjoyed it. My complaint is that I think instead of being a good movie, it could have been a great movie.

GM: Given the change in opinion regarding same-sex couples in recent years, do you think the protagonist in Martian Child would have remained a gay single father if the film were in production now?

DG: I’m certain that if we had the opportunity to remake the movie now, it would be a lot closer to the novel and the hero would definitely be gay. I’d love the chance to do it right.

GM: During your time with the Star Trek franchise, the idea of same-sex marriages must have seemed like it was far into the future. Same-sex marriages are now legal in sixteen states and the District of Columbia, and the federal government officially recognizes such marriages. Did you think you would see such progress in your lifetime?

DG: Back in the 70s, I had assumed that same-sex marriage would become legal sometime in the 90s. I was right and wrong. The first effort to legalize same-sex marriage began in the 90s. What I was wrong about was that I did not realize the anti-gay backlash that would invest so much time and money in delaying what I believed was inevitable.

[...]I think there was a lot of resistance to the legalization of same-sex marriage, even after Massachusetts proved it wasn’t the end of the world. A lot of people were having trouble getting comfortable with the idea. But I think the tipping point happened in large part because of the passage of Proposition 8 in CA. That was a deliberate attempt to take away the right to marry. That created outrage. But more than that, it changed the conversation. Prior to that, the conversation was “the sanctity of marriage,” but after the passage of Prop 8, the perception shifted to marriage as a civil right.

By the time Prop 8 got to the Supreme Court, the momentum for marriage equality was unstoppable. The 2012 elections legalized it in three states. The Supreme Court rulings on DOMA and Prop 8 served as a signal that there was no basis in law for the denial of marriage equality. So I expect to see marriage equality nationwide within five years, maybe less.

GM: How do you account for the relative speed, when compared with other long-term movements like women’s suffrage or the civil rights movement, with which same-sex marriage has garnered public support?

DG: I think one of the factors, possibly the greatest factor, was simply that gay men and lesbians stopped being invisible.

[...]The gay civil rights movement started in June of 1969 with the Stonewall rebellion in New York City. That’s only 44 years ago. No other civil rights movement has come so far so fast. [...]As I experienced it, the first decade after Stonewall was LGBT people trying to figure out what it meant to be gay.

For so many decades, the definition of homosexuality had been controlled by others. Heterosexual doctors said it was an illness, heterosexual legislators said it was a crime, heterosexual psychiatrists said it was a mental disorder, heterosexual(?) [author’s question mark] priests said it was a sin. There was a common factor in all those judgments.

After Stonewall, gay men and lesbians chose to own that conversation: “We don’t recognize ourselves or our experiences in what you’re saying.”

That’s when we started to see some genuinely useful research into the biological, hormonal, gestational, cultural causes of homosexuality. That’s when gay men and women stopped accepting the idea that they should be ashamed. That’s why the celebrations are called Pride celebrations.

GM: Is there anyone, in your opinion, who stands out as a leader during that movement?

DG: Harvey Milk was a singularly important voice. He said, “Come out. Come out to your parents, your siblings, your friends, your colleagues, your co-workers, your neighbors. Once they know you, once they know a gay person, it’s harder to hate gay people.” There was a lot of courage in that statement—and it took even more courage for gay men and lesbians to come out when there was so little agreement, when the cultural conversation was one of ridicule and enmity.

But every gay person who ever came out made it easier for the next one. And every time a famous person came out, that helped shift the conversation a little further too. Rock Hudson was a hero for that. He made it safe for people to talk about it. And the more that people talked about it, the less fear and the less enmity there was.

GM: Your work has certainly helped shift the conversation. You’ve also been quite outspoken regarding intolerant writers and politicians. A notable example of this is your Facebook post from July 9, 2013 regarding the homophobia of Ender’s Game author Orson Scott Card. How do you plan to continue fighting homophobia and intolerance?

DG: I’m going to continue what I’ve been doing. Writing what I can, speaking out where I have to.

[…]But the issue isn’t homophobia. It’s disrespect. Human beings can be self-righteous, judgmental, miserably prejudiced, malicious little monsters, an insult to the 98% of our DNA that we share with chimpanzees. The best part about human beings is that we have the ability to rise above that level. The most shameful part is that so many of us don’t.

So it’s not about LGBT issues. It’s about African-Americans, Native-Americans, Asians, old people, fat people, disabled people, homosexual people, transgender people, developmentally challenged people, mentally ill people — all the different categories that we assign, all the different labels that we apply, thinking that the label is also an explanation.

Based on the evidence of the things that people tell me in their emails and public posts on Facebook, I have to assume that some people are getting it.

A few weeks ago, I posted about how the LGB part of the LGBT community hasn’t stood up for the T part, the transgender men and women, as well as it should be doing. A few weeks before that, I ranted about how people post anonymous pictures of fat or ill-dressed people with the intention of mocking them. The whole “people of Walmart” thing. Why are we sitting in judgment of others? Why are we fat-shaming people? Why aren’t we looking at those pictures with sympathy for people who are different?

[...] Okay, yeah—I have to wonder about someone who becomes morbidly obese, or who goes to Walmart dressed in bizarre clothing—but if I don’t like being judged, then why should I assume it’s all right to judge others? If we’re not going to learn respect for diversity within our own species, we’re sure as hell not going to learn it when we go out to the stars.

GM: Venturing to the stars has been a recurring theme throughout your career, including your work on the Star Trek: New Voyages/Phase II web series, which has had a profound impact on audiences. When you adapted and directed the two-part “Blood and Fire” (from a script originally intended for Star Trek: The Next Generation twenty years prior), you made a background same-sex couple into a central focus of the story. Why did you feel that this change was an important one?

DG: Most of the credit for that goes to [New Voyages creator and then-lead actor] James Cawley, who felt that the story would be stronger if one of the gay characters was Captain Kirk’s nephew, Peter Kirk. As we developed the script, we realized that we had to expand the subplot to make Peter Kirk’s relationship with [fellow crew-member] Alex a much stronger storyline. It couldn’t be incidental. Originally, we were just going to have the two of them kiss, just to show they were lovers— then I had the idea that Peter should be frustrated about not being put on the mission team, and from there it seemed obvious that he should propose to Alex and then ask Captain Kirk to perform the wedding. That way we could demonstrate the seriousness of their love as well as Peter’s commitment to being a responsible crew member. The scene where Peter confronts Kirk played beautifully.

He says that if he’s not treated like any other crew member, he’ll have to ask for a transfer—and so will his husband. That is, if Kirk will perform the wedding. Bobby Quinn Rice [as Peter Kirk] is a wonderful actor and James Cawley owned the moment with a perfect reaction of startlement and bemusement.

It became apparent to all of us that the story wasn’t just about Peter’s relationship with Alex, it was also about his strained relationship with Kirk. Once we recognized those relationships, the rest of the story crystallized perfectly.

GM: Were you pleased with the end result?

DG: That made for one of the most intense Star Trek stories I ever had the privilege of writing. I loved the way it turned out. The cast and crew did an extraordinary job bringing it to life. Whenever we’ve screened it at a convention, audiences have given us standing ovations.

GM: That’s got to be a great feeling. Part of the reason for such a warm reception, I’m sure, is that it encapsulates the best ideals of science fiction: using futuristic situations to challenge readers’ preconceptions.

DG: The job of the writer is to wake people up, to disturb them, to change the way they see the universe. The very best writers in the world have changed the world. In science fiction, we have authors like Heinlein, Clarke, Asimov, LeGuin, Phil Dick, Joanna Russ, and so many more, who’ve had impact that’s world-changing. I can’t begin to list all the examples.

GM: Can you give us just one?

DG: One of my heroes is a guy named Larry Kramer. Never met him, but I admire him ferociously for his activism during the worst days of the AIDS crisis in the 80s. He’s the guy who said, “Silence equals death.” He was right. More than right. That is possibly the single most important assertion about any civil rights issue. Silence allows people to ignore you. Silence allows people to be comfortable and undisturbed. Silence is an accomplice of the status quo. The status quo is the enemy.

GM: Interesting that you should say that. In early October, you posted on your Facebook page that you believe... “authors —especially authors—should be outspoken. Great writing is subversive. Great authors challenge the status quo.” With that in mind, how do you feel that your writing has challenged—or challenges—the status quo?

DG: I think history will judge that better than anything I can say.

[…]I’d like to believe that The Man Who Folded Himself helped make things a little safer for LGBT people. I’d like to believe that The War Against The Chtorr has helped make people a little more conscious of ecology.

[...] For me, the issue is that we learn to respect and cherish the spark of humanity that lives inside each of us. It’s not an easy job—because I think too many of us have given up and resigned ourselves to playing smaller than we really are. As a writer, I think my job is to move, touch, and inspire.

But if nothing else, if all I’m ever remembered for is “The Trouble With Tribbles,” then I know that I’ve made millions of people laugh out loud. That’s pretty good too.

DG: I did acknowledge being gay in the book, but I didn’t give it much attention, because I thought Sean was the more important story. I did report a couple of the conversations we’d had about my being gay, he accepted it and that was pretty much it. From my point of view, it was one of the least important parts of the adoption process. It was almost irrelevant to our relationship.

GM: But your editor felt it was necessary to include in the expanded novel?

DG: At the time, the anti-marriage forces were arguing that gay people could not be good parents and shouldn’t be allowed to adopt. They were making children the issue. Sean had been with me for a few years by then, and my reaction was, “You have it half-right. Yes, children are the issue. There are a lot of kids in the system who aren’t being adopted because there’s a critical shortage of qualified adoptive parents. Gay parents give those kids a chance at a real family.” But I didn’t want to write a polemic. I wanted to stay true to the theme of the original story, that my son and I were a family and just have that story stand as a simple refutation. Other gay adoptive parents have written more about their experiences because that’s where their attention was and I applaud them for it. That wasn’t the case here. I was more concerned with the needs of my son than making a political or social point. My son was my focus. The book was an afterthought.

GM: Is there anything else you have to reveal about parenting in relation to the needs of your son Sean?

DG: I think that the three lessons I learned from the entire process are so simple that we don’t realize how important they are.

The first is: Always take care of your own well-being. Kids look to their parents as the source of all well-being in the universe. If you don’t take care of your own well-being you have nothing to give to anyone else.

The second is: Never never never never never give up.

The third is: Never never never never never lose your sense of humor.

GM: You’re right. We often forget how important they are. These lessons obviously resonated with audiences; the book became popular enough to win several awards and be adapted by Seth Bass and Jonathan Tolins into the motion picture Martian Child. For this adaptation, though, the main character was changed from a gay single father to a straight widower.

DG: I don’t know whose decision it was to straight-wash the character. […]I wasn’t consulted about the changes. I did write some memos. I did make the novel available to them, but according to their public statements, they based their script entirely on the novella and never read the novel. It’s a weird assertion because so many plot points in the movie parallel plot points in the novel.

GM: How do you think the orientation change affected the story and its impact on your audience?

DG: I thought it weakened the picture. But that wasn’t the only part of the script that I felt was weak. In the novella and the novel, the hero does his research, he comes to the adoption well-prepared for the challenges. In the script, the hero seems totally inept at parenting—even worse, he makes some very un-adult decisions in how to deal with the boy.

In the movie, Dennis is portrayed as weird. In real life, Sean wasn’t weird. He was thoughtful, big-hearted, curious, and trusting. Yes, he had issues—and they were dramatic issues. Based on the evidence of the script, the screenwriters didn’t trust the source material and felt they had to add all kinds of weird stuff like sunglasses and weight belts and umbrellas. In my opinion, they missed the point — the story is about building a family and how father and son both discover their own humanity in the process.

[...]A key sequence in the novel is the “Pickled Mongoose” incident—where Sean learned how to tell jokes. That’s the moment that shows the first connection between father and son, the first time that the Martian child is learning how to be human. I think it’s the most important part of the story, because it’s the turning point in the relationship. That’s the sequence I want to see on the screen.

A lot of people were charmed by the movie and I’m glad they enjoyed it. My complaint is that I think instead of being a good movie, it could have been a great movie.

GM: Given the change in opinion regarding same-sex couples in recent years, do you think the protagonist in Martian Child would have remained a gay single father if the film were in production now?

DG: I’m certain that if we had the opportunity to remake the movie now, it would be a lot closer to the novel and the hero would definitely be gay. I’d love the chance to do it right.

GM: During your time with the Star Trek franchise, the idea of same-sex marriages must have seemed like it was far into the future. Same-sex marriages are now legal in sixteen states and the District of Columbia, and the federal government officially recognizes such marriages. Did you think you would see such progress in your lifetime?

DG: Back in the 70s, I had assumed that same-sex marriage would become legal sometime in the 90s. I was right and wrong. The first effort to legalize same-sex marriage began in the 90s. What I was wrong about was that I did not realize the anti-gay backlash that would invest so much time and money in delaying what I believed was inevitable.

[...]I think there was a lot of resistance to the legalization of same-sex marriage, even after Massachusetts proved it wasn’t the end of the world. A lot of people were having trouble getting comfortable with the idea. But I think the tipping point happened in large part because of the passage of Proposition 8 in CA. That was a deliberate attempt to take away the right to marry. That created outrage. But more than that, it changed the conversation. Prior to that, the conversation was “the sanctity of marriage,” but after the passage of Prop 8, the perception shifted to marriage as a civil right.

By the time Prop 8 got to the Supreme Court, the momentum for marriage equality was unstoppable. The 2012 elections legalized it in three states. The Supreme Court rulings on DOMA and Prop 8 served as a signal that there was no basis in law for the denial of marriage equality. So I expect to see marriage equality nationwide within five years, maybe less.

GM: How do you account for the relative speed, when compared with other long-term movements like women’s suffrage or the civil rights movement, with which same-sex marriage has garnered public support?

DG: I think one of the factors, possibly the greatest factor, was simply that gay men and lesbians stopped being invisible.

[...]The gay civil rights movement started in June of 1969 with the Stonewall rebellion in New York City. That’s only 44 years ago. No other civil rights movement has come so far so fast. [...]As I experienced it, the first decade after Stonewall was LGBT people trying to figure out what it meant to be gay.

For so many decades, the definition of homosexuality had been controlled by others. Heterosexual doctors said it was an illness, heterosexual legislators said it was a crime, heterosexual psychiatrists said it was a mental disorder, heterosexual(?) [author’s question mark] priests said it was a sin. There was a common factor in all those judgments.

After Stonewall, gay men and lesbians chose to own that conversation: “We don’t recognize ourselves or our experiences in what you’re saying.”

That’s when we started to see some genuinely useful research into the biological, hormonal, gestational, cultural causes of homosexuality. That’s when gay men and women stopped accepting the idea that they should be ashamed. That’s why the celebrations are called Pride celebrations.

GM: Is there anyone, in your opinion, who stands out as a leader during that movement?

DG: Harvey Milk was a singularly important voice. He said, “Come out. Come out to your parents, your siblings, your friends, your colleagues, your co-workers, your neighbors. Once they know you, once they know a gay person, it’s harder to hate gay people.” There was a lot of courage in that statement—and it took even more courage for gay men and lesbians to come out when there was so little agreement, when the cultural conversation was one of ridicule and enmity.

But every gay person who ever came out made it easier for the next one. And every time a famous person came out, that helped shift the conversation a little further too. Rock Hudson was a hero for that. He made it safe for people to talk about it. And the more that people talked about it, the less fear and the less enmity there was.

GM: Your work has certainly helped shift the conversation. You’ve also been quite outspoken regarding intolerant writers and politicians. A notable example of this is your Facebook post from July 9, 2013 regarding the homophobia of Ender’s Game author Orson Scott Card. How do you plan to continue fighting homophobia and intolerance?

DG: I’m going to continue what I’ve been doing. Writing what I can, speaking out where I have to.

[…]But the issue isn’t homophobia. It’s disrespect. Human beings can be self-righteous, judgmental, miserably prejudiced, malicious little monsters, an insult to the 98% of our DNA that we share with chimpanzees. The best part about human beings is that we have the ability to rise above that level. The most shameful part is that so many of us don’t.

So it’s not about LGBT issues. It’s about African-Americans, Native-Americans, Asians, old people, fat people, disabled people, homosexual people, transgender people, developmentally challenged people, mentally ill people — all the different categories that we assign, all the different labels that we apply, thinking that the label is also an explanation.

Based on the evidence of the things that people tell me in their emails and public posts on Facebook, I have to assume that some people are getting it.

A few weeks ago, I posted about how the LGB part of the LGBT community hasn’t stood up for the T part, the transgender men and women, as well as it should be doing. A few weeks before that, I ranted about how people post anonymous pictures of fat or ill-dressed people with the intention of mocking them. The whole “people of Walmart” thing. Why are we sitting in judgment of others? Why are we fat-shaming people? Why aren’t we looking at those pictures with sympathy for people who are different?

[...] Okay, yeah—I have to wonder about someone who becomes morbidly obese, or who goes to Walmart dressed in bizarre clothing—but if I don’t like being judged, then why should I assume it’s all right to judge others? If we’re not going to learn respect for diversity within our own species, we’re sure as hell not going to learn it when we go out to the stars.

GM: Venturing to the stars has been a recurring theme throughout your career, including your work on the Star Trek: New Voyages/Phase II web series, which has had a profound impact on audiences. When you adapted and directed the two-part “Blood and Fire” (from a script originally intended for Star Trek: The Next Generation twenty years prior), you made a background same-sex couple into a central focus of the story. Why did you feel that this change was an important one?

DG: Most of the credit for that goes to [New Voyages creator and then-lead actor] James Cawley, who felt that the story would be stronger if one of the gay characters was Captain Kirk’s nephew, Peter Kirk. As we developed the script, we realized that we had to expand the subplot to make Peter Kirk’s relationship with [fellow crew-member] Alex a much stronger storyline. It couldn’t be incidental. Originally, we were just going to have the two of them kiss, just to show they were lovers— then I had the idea that Peter should be frustrated about not being put on the mission team, and from there it seemed obvious that he should propose to Alex and then ask Captain Kirk to perform the wedding. That way we could demonstrate the seriousness of their love as well as Peter’s commitment to being a responsible crew member. The scene where Peter confronts Kirk played beautifully.

He says that if he’s not treated like any other crew member, he’ll have to ask for a transfer—and so will his husband. That is, if Kirk will perform the wedding. Bobby Quinn Rice [as Peter Kirk] is a wonderful actor and James Cawley owned the moment with a perfect reaction of startlement and bemusement.

It became apparent to all of us that the story wasn’t just about Peter’s relationship with Alex, it was also about his strained relationship with Kirk. Once we recognized those relationships, the rest of the story crystallized perfectly.

GM: Were you pleased with the end result?

DG: That made for one of the most intense Star Trek stories I ever had the privilege of writing. I loved the way it turned out. The cast and crew did an extraordinary job bringing it to life. Whenever we’ve screened it at a convention, audiences have given us standing ovations.

GM: That’s got to be a great feeling. Part of the reason for such a warm reception, I’m sure, is that it encapsulates the best ideals of science fiction: using futuristic situations to challenge readers’ preconceptions.

DG: The job of the writer is to wake people up, to disturb them, to change the way they see the universe. The very best writers in the world have changed the world. In science fiction, we have authors like Heinlein, Clarke, Asimov, LeGuin, Phil Dick, Joanna Russ, and so many more, who’ve had impact that’s world-changing. I can’t begin to list all the examples.

GM: Can you give us just one?

DG: One of my heroes is a guy named Larry Kramer. Never met him, but I admire him ferociously for his activism during the worst days of the AIDS crisis in the 80s. He’s the guy who said, “Silence equals death.” He was right. More than right. That is possibly the single most important assertion about any civil rights issue. Silence allows people to ignore you. Silence allows people to be comfortable and undisturbed. Silence is an accomplice of the status quo. The status quo is the enemy.

GM: Interesting that you should say that. In early October, you posted on your Facebook page that you believe... “authors —especially authors—should be outspoken. Great writing is subversive. Great authors challenge the status quo.” With that in mind, how do you feel that your writing has challenged—or challenges—the status quo?

DG: I think history will judge that better than anything I can say.

[…]I’d like to believe that The Man Who Folded Himself helped make things a little safer for LGBT people. I’d like to believe that The War Against The Chtorr has helped make people a little more conscious of ecology.

[...] For me, the issue is that we learn to respect and cherish the spark of humanity that lives inside each of us. It’s not an easy job—because I think too many of us have given up and resigned ourselves to playing smaller than we really are. As a writer, I think my job is to move, touch, and inspire.

But if nothing else, if all I’m ever remembered for is “The Trouble With Tribbles,” then I know that I’ve made millions of people laugh out loud. That’s pretty good too.