In Bits and Pieces

by Cole Brayfield

Theatrical release poster by Macario Gómez Quibus

Theatrical release poster by Macario Gómez Quibus

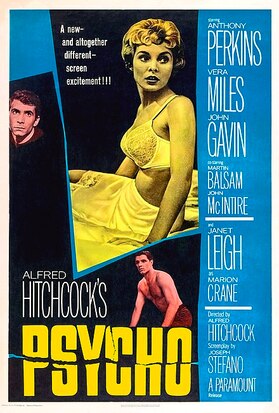

Psycho (1960)

Dir. Alfred Hitchcock

Late one night, when I was a teenager, I watched Psycho with my mom, and she quickly fell asleep on the couch. I did not. I became enthralled by the film’s menacing score and shadowy images, its measured crawl. I found the handsome Anthony Perkins twisted but irresistible. I tensed in terror when Perkins as Norman Bates was revealed in the fruit cellar, not because I was afraid of him—I adored him—but because I began to understand the way the world was afraid of me. I curled my toes as he sat wrapped in a blanket, dark eyes and a dark smile, the voice in his head ruminating over a fly, the frame withering, his face becoming skeletal.

That first viewing of Psycho lead to an obsession with cinema and with Hitchcock, and I sought his other films. Greater than my appreciation for Hitchcock’s filmmaking was my infatuation with his leading men, particularly Perkins and Farley Granger. As a teenager, I adored the stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age. I’d spend hours researching the love lives of men like Perkins, Granger, James Dean, Marlon Brando, and Montgomery Clift. I struggled to reconcile my envy of and attraction toward them, their jaws, their smiles, the incredible sex they must’ve had with one another, the fantasy.

Anthony Perkins was never open about having relationships with men. He was married to his wife, Berry Berenson, until his death in 1992 of complications with AIDS. Reflecting on Perkins’ hospital visits in which they would check in under different names, Berenson was quoted in a New York Times article saying, “I literally asked myself, Who am I today? It was weird. You lose all sense of reality. You can’t even be yourself in a situation like this. You’re signing ‘Mrs. Smith’ or whatever.” When asked how Perkins might have contracted AIDS, Berenson said, “No. We don’t really know. No. It’s not worth it.” There’s something crushing in her words, something honest. Berenson died nine years later aboard American Airlines Flight 11.

Tab Hunter, another Golden-Age icon, dated Perkins for a while in the late Fifties. My first summer home from college, I hooked up my dorm-room TV in my childhood bedroom. I felt some strange freedom as I sequestered, able to watch things away from prying eyes; after a year of close-quarters dorm life, that tiny black box, a portal to gayer dimensions, bloomed like orchids in the newly formed sanctuary of my bedroom. I found myself in its glare, volume low as others in the house slept. On that TV, I watched a documentary about Tab Hunter’s life as a gay man in Hollywood. In it, Hunter’s voiceover describes Perkins as duplicitous and secretive as a series of photos of Perkins show him sporting the infamous stare that he wore as Norman Bates at the end of Psycho.

An actress that accompanied the pair publicly as a sort of beard says that Perkins would frequently arrive to her apartment in tears after fighting with Hunter. She says that Tony loved Tab more than Tab loved Tony. Both men were profoundly closeted at the time, just as I was when I first watched the documentary hidden in my bedroom. My image of these men ruptured, like a framed photo above a fireplace tumbling toward brick.

Thesis 1: Slasher films recognize

violence. I chew my mouth; sores line my lower lip. I pull hairs from my arm. I dig my nails into my skin and breathe through my mouth. There’s an everyday trauma.

The slash, stab, slice, smash, burn, bash, butcher, bludgeon of

fluorescent faces and bank balances. Of crowded sidewalks. Of swimming pools. Of bent reflections. I have this recurring daydream. Palms on either side of my head. Fingernails grip my scalp. Rip, tear, pull. Cracked open, black fog spills out, and my mind is finally clear.

Dir. Alfred Hitchcock

Late one night, when I was a teenager, I watched Psycho with my mom, and she quickly fell asleep on the couch. I did not. I became enthralled by the film’s menacing score and shadowy images, its measured crawl. I found the handsome Anthony Perkins twisted but irresistible. I tensed in terror when Perkins as Norman Bates was revealed in the fruit cellar, not because I was afraid of him—I adored him—but because I began to understand the way the world was afraid of me. I curled my toes as he sat wrapped in a blanket, dark eyes and a dark smile, the voice in his head ruminating over a fly, the frame withering, his face becoming skeletal.

That first viewing of Psycho lead to an obsession with cinema and with Hitchcock, and I sought his other films. Greater than my appreciation for Hitchcock’s filmmaking was my infatuation with his leading men, particularly Perkins and Farley Granger. As a teenager, I adored the stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age. I’d spend hours researching the love lives of men like Perkins, Granger, James Dean, Marlon Brando, and Montgomery Clift. I struggled to reconcile my envy of and attraction toward them, their jaws, their smiles, the incredible sex they must’ve had with one another, the fantasy.

Anthony Perkins was never open about having relationships with men. He was married to his wife, Berry Berenson, until his death in 1992 of complications with AIDS. Reflecting on Perkins’ hospital visits in which they would check in under different names, Berenson was quoted in a New York Times article saying, “I literally asked myself, Who am I today? It was weird. You lose all sense of reality. You can’t even be yourself in a situation like this. You’re signing ‘Mrs. Smith’ or whatever.” When asked how Perkins might have contracted AIDS, Berenson said, “No. We don’t really know. No. It’s not worth it.” There’s something crushing in her words, something honest. Berenson died nine years later aboard American Airlines Flight 11.

Tab Hunter, another Golden-Age icon, dated Perkins for a while in the late Fifties. My first summer home from college, I hooked up my dorm-room TV in my childhood bedroom. I felt some strange freedom as I sequestered, able to watch things away from prying eyes; after a year of close-quarters dorm life, that tiny black box, a portal to gayer dimensions, bloomed like orchids in the newly formed sanctuary of my bedroom. I found myself in its glare, volume low as others in the house slept. On that TV, I watched a documentary about Tab Hunter’s life as a gay man in Hollywood. In it, Hunter’s voiceover describes Perkins as duplicitous and secretive as a series of photos of Perkins show him sporting the infamous stare that he wore as Norman Bates at the end of Psycho.

An actress that accompanied the pair publicly as a sort of beard says that Perkins would frequently arrive to her apartment in tears after fighting with Hunter. She says that Tony loved Tab more than Tab loved Tony. Both men were profoundly closeted at the time, just as I was when I first watched the documentary hidden in my bedroom. My image of these men ruptured, like a framed photo above a fireplace tumbling toward brick.

Thesis 1: Slasher films recognize

violence. I chew my mouth; sores line my lower lip. I pull hairs from my arm. I dig my nails into my skin and breathe through my mouth. There’s an everyday trauma.

The slash, stab, slice, smash, burn, bash, butcher, bludgeon of

fluorescent faces and bank balances. Of crowded sidewalks. Of swimming pools. Of bent reflections. I have this recurring daydream. Palms on either side of my head. Fingernails grip my scalp. Rip, tear, pull. Cracked open, black fog spills out, and my mind is finally clear.

~

Theatrical release poster by Robert Gleason

Theatrical release poster by Robert Gleason

Halloween (1978)

Dir. John Carpenter

Halloween’s effectiveness is entirely a result of its score, evidenced by its initial would-be distributors who were unimpressed by an early pre-score cut. Halloween is a familiar comfort. When I revisit the film every year, hear its score and see its jack-o-lantern title, I smile, settling in.

As a kid, before I’d ever seen Halloween, my friend D showed me how to play the theme on the piano. I sat next to him on the piano bench, watching his fingers methodically dance atop the keys. D and I watched a lot of horror movies together, gritty, early-aughts fare. He would tell me that horror movies made him think of me.

The Christmas before I graduated with my master’s, my parents revealed, in somewhat dramatic fashion as we stood around their kitchen island, that D had a boyfriend.

“We’re not supposed to tell anyone, Paul,” my mom said, feigning innocence.

“Of course we’re going to tell him,” my dad said.

My parents said D’s parents didn’t approve, that his parents sobbed when they told my parents, and I chuckled at the thought of D’s parents confiding in my parents, ostensibly experts on how to deal with a gay son. I came out my second year of college—four years prior to this kitchen-island conversation—after meeting my husband, S.

“They’re not telling anyone else,” my mom said, “so if anyone asks, you don’t know.”

I had questions. I thought about the way D and I used to wrestle. Memories of watching gay director Carter Smith’s The Ruins one Florida vacation returned vivid in my mind, and I wondered if he desired the film’s male bodies in the same way I did as we sat close on the small hotel couch that barely contained us.

Six months after the kitchen-island conversation about D, my parents told me D’s parents were having a Fourth of July party. They said D and his boyfriend would be there, and I had these daydreams about what I’d do if I saw D again, both of us adults, neither of us closeted. I imagined hugging him, neither of us saying a word, though I couldn’t remember us ever hugging before. I imagined some kind of unspoken understanding as we embraced.

S and I visited my parents for the Fourth. The night before the Fourth, S and I arrived at some stranger’s house by a lake. In the backyard, D and his boyfriend lit fireworks for the assembled crowd. I stood close to my parents, feeling uncomfortable. My husband eventually made his way out to D and his boyfriend. S mingled effortlessly, lighting a few fireworks himself. I pretended to like the beer I drank.

The next day, we arrived around noon at D’s parents’ house. The house felt both familiar and entirely foreign. Where the piano once sat, a massive TV streamed Fortnite for D’s nephew. Outside, after losing several cornhole games and feelingly hopelessly unathletic, I grabbed another beer. S sat next to me and said matter-of-factly, “I find him attractive.” He gestured to D, adding, “It makes me feel good about myself because I think we have similar body types.” He wasn’t wrong, and I knew S hadn’t meant anything by the comment, but I also didn’t know, not really, not truly, deeply. I was hopelessly insecure.

I panicked, heading inside to cool off. Passing D’s childhood bedroom on the way to the bathroom, I noticed an air mattress on the floor, so he and his boyfriend didn’t share a bed. In the bathroom, I pressed my eyes back deep in their sockets. What’s my body type? I wondered, examining myself in the bathroom mirror. Coming here, back home, to this party, was a mistake.

For the next half hour, I drifted in the pool, pouting, alone. Listening to my husband laugh with D and his boyfriend as they played cornhole, I realized that I didn’t fit in. Even though we were all gay, even though I was an adult in a committed relationship, I was brooding in the corner at some party, still a child.

I barely spoke to D or his boyfriend.

Thesis 2: In the slasher, isolation and loneliness mean survival. Only the Final Girl lives. I don’t want to be the last one standing.

Dir. John Carpenter

Halloween’s effectiveness is entirely a result of its score, evidenced by its initial would-be distributors who were unimpressed by an early pre-score cut. Halloween is a familiar comfort. When I revisit the film every year, hear its score and see its jack-o-lantern title, I smile, settling in.

As a kid, before I’d ever seen Halloween, my friend D showed me how to play the theme on the piano. I sat next to him on the piano bench, watching his fingers methodically dance atop the keys. D and I watched a lot of horror movies together, gritty, early-aughts fare. He would tell me that horror movies made him think of me.

The Christmas before I graduated with my master’s, my parents revealed, in somewhat dramatic fashion as we stood around their kitchen island, that D had a boyfriend.

“We’re not supposed to tell anyone, Paul,” my mom said, feigning innocence.

“Of course we’re going to tell him,” my dad said.

My parents said D’s parents didn’t approve, that his parents sobbed when they told my parents, and I chuckled at the thought of D’s parents confiding in my parents, ostensibly experts on how to deal with a gay son. I came out my second year of college—four years prior to this kitchen-island conversation—after meeting my husband, S.

“They’re not telling anyone else,” my mom said, “so if anyone asks, you don’t know.”

I had questions. I thought about the way D and I used to wrestle. Memories of watching gay director Carter Smith’s The Ruins one Florida vacation returned vivid in my mind, and I wondered if he desired the film’s male bodies in the same way I did as we sat close on the small hotel couch that barely contained us.

Six months after the kitchen-island conversation about D, my parents told me D’s parents were having a Fourth of July party. They said D and his boyfriend would be there, and I had these daydreams about what I’d do if I saw D again, both of us adults, neither of us closeted. I imagined hugging him, neither of us saying a word, though I couldn’t remember us ever hugging before. I imagined some kind of unspoken understanding as we embraced.

S and I visited my parents for the Fourth. The night before the Fourth, S and I arrived at some stranger’s house by a lake. In the backyard, D and his boyfriend lit fireworks for the assembled crowd. I stood close to my parents, feeling uncomfortable. My husband eventually made his way out to D and his boyfriend. S mingled effortlessly, lighting a few fireworks himself. I pretended to like the beer I drank.

The next day, we arrived around noon at D’s parents’ house. The house felt both familiar and entirely foreign. Where the piano once sat, a massive TV streamed Fortnite for D’s nephew. Outside, after losing several cornhole games and feelingly hopelessly unathletic, I grabbed another beer. S sat next to me and said matter-of-factly, “I find him attractive.” He gestured to D, adding, “It makes me feel good about myself because I think we have similar body types.” He wasn’t wrong, and I knew S hadn’t meant anything by the comment, but I also didn’t know, not really, not truly, deeply. I was hopelessly insecure.

I panicked, heading inside to cool off. Passing D’s childhood bedroom on the way to the bathroom, I noticed an air mattress on the floor, so he and his boyfriend didn’t share a bed. In the bathroom, I pressed my eyes back deep in their sockets. What’s my body type? I wondered, examining myself in the bathroom mirror. Coming here, back home, to this party, was a mistake.

For the next half hour, I drifted in the pool, pouting, alone. Listening to my husband laugh with D and his boyfriend as they played cornhole, I realized that I didn’t fit in. Even though we were all gay, even though I was an adult in a committed relationship, I was brooding in the corner at some party, still a child.

I barely spoke to D or his boyfriend.

Thesis 2: In the slasher, isolation and loneliness mean survival. Only the Final Girl lives. I don’t want to be the last one standing.

~

Theatrical release poster

Theatrical release poster

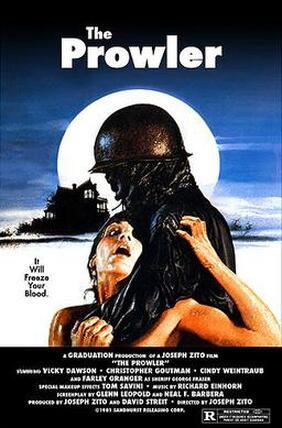

The Prowler (1981)

Dir. Joseph Zito

I try to avoid looking down. When I look down, my receding hairline is visible. S knows that I’m afraid of losing my hair. “If you’re worried about it, shave your head now,” he says, showing me pictures of impossibly attractive bald men. “Be confident.” He tries. I’ve always struggled with confidence—I’ve only just begun to feel that struggle fade.

Years ago, I read that the average person loses twenty hairs every time they shower. I used to count. I’m still gentle as I massage the wet mass of fragile tendrils extending from my scalp.

The Prowler came out in the midst of the early-eighties American slasher craze following Halloween. It’s standard slasher fare. For many, it’s unremarkable. For me, it was a milestone. I knew The Prowler existed long before I watched it, but I waited, pushing it off for years. Farley Granger appears in the film. He was fifty-five at the time of filming.

Farley Granger was my favorite actor when I discovered him as a teenager. He’s best known for his films with Hitchcock, Rope and Strangers on a Train. Outside of those films, he’s not well known, but I adored him; he was deeply uncomfortable with having fans.

I read his autobiography, Include Me Out, the summer before college, when I was eighteen, desperate, and closeted. In a chapter titled “Sex, Sex, Sex, Sex…”, he details the night that he lost his virginity. He begins, “I was thinking about sex all the time. I was twenty and still a virgin.” I also thought about sex constantly, and at the time, I compared myself to that number: twenty. Would I still be closeted, still a virgin, when I was twenty? While in the Navy, Granger was stationed in Honolulu. A friend of his found an escort service for Granger, and he met with “an absolutely ravishing young Hawaiian woman” at night in the backyard of a massive estate. He swam naked in the pool until she arrived. When she did, she complimented his body. They talked for a while, and he says she was well-educated. He says when they began, she made him take his time; she slowed him down. They made love twice, he says. He fell asleep, and when he woke up, she was gone. Still nighttime, Granger went to get his clothes but found a man sitting at the bar by the pool. He complimented Granger’s body too, and they also sat and talked. The man was a lieutenant commander in the Navy, and he was scheduled to deploy the next day. Suddenly, he pulled Granger into his arms, and Granger resisted until he realized how excited he was. Granger says they made love for hours. He never saw the lieutenant after that night.

The night I finished “Sex, Sex, Sex, Sex…,” my parents were out of town, and I snuck into our neighborhood’s pool after it had closed. As I removed my shirt, I ran my fingers along the crests and valleys of my form, my newly bursting shoulders, and the molded lines of my obliques. Like a stream, muscles flowed down the length of me, the heavenly core in my chest thrusting, heaving, sighing; I was nervous. In the cool darkness, I did laps trying to replicate what had worked for Farley. I’m not a good swimmer.

I sometimes wonder—I used to wonder more often—what would’ve happened if I had downloaded Grindr the night I read that chapter, if I had been brave enough. I think of the anticipation that may have tightened my chest, the deep breaths I may have taken as my lungs worked to still my shaking frame. I think of lips meeting my skin, the neck I may have kissed, the back I may have held, the arms that may have held me.

When I was eighteen, I thought about Granger’s chapter all the time. When I read the chapter now, it feels too clean, too tidy. Granger’s sex feels like a Hollywood sex scene, indescribably romantic and indistinct, quick to pan away to blowing curtains. He had sex with a woman and a man. How did he have sex with that man? Did they fuck? How did they fuck? Sex, sex, sex, sex. Four times. Is that how many times Granger came that night? What did he actually do? What is making love? I’ve had sex and loved the man I had sex with, but I don’t know if I’ve made love.

When I finally watched The Prowler, Granger looked nearly unrecognizable to me. I suppose he doesn’t look that old; he was only fifty-five. But he certainly doesn’t look the same as in his Hitchcock films or how I imagine him swimming in that Honolulu pool. His hair is grey. Granger only appears early in The Prowler for a couple short scenes then disappears until the Final Girl’s confrontation with the killer. The killer rips off his mask, revealing himself to be Granger. He wrestles a shotgun from the Final Girl and shoots himself. His face explodes in chunks. Unrecognizable.

Granger doesn’t write about The Prowler in Include Me Out. I wonder if he only did the movie for money. Or as a favor. Was he embarrassed by the film? When I was younger, I stopped reading Include Me Out about a third of the way through because I couldn’t stand the thought of Granger growing old. Now, I’ve seen The Prowler, confronted his aging face, and finished his memoir, and I can only think, at least he still had his hair at fifty-five.

Thesis 3: Slashers scrutinize the body, each cut incisive, the careful dissection a confession of imperfect flesh and muscle. My mirror is a screen; fragile glass in harsh light reflects the uneven lines and irregular outline of my jaw, shoulders, and abdomen. Hairs and moles are little monsters forming the derelict landscape of my skin.

Dir. Joseph Zito

I try to avoid looking down. When I look down, my receding hairline is visible. S knows that I’m afraid of losing my hair. “If you’re worried about it, shave your head now,” he says, showing me pictures of impossibly attractive bald men. “Be confident.” He tries. I’ve always struggled with confidence—I’ve only just begun to feel that struggle fade.

Years ago, I read that the average person loses twenty hairs every time they shower. I used to count. I’m still gentle as I massage the wet mass of fragile tendrils extending from my scalp.

The Prowler came out in the midst of the early-eighties American slasher craze following Halloween. It’s standard slasher fare. For many, it’s unremarkable. For me, it was a milestone. I knew The Prowler existed long before I watched it, but I waited, pushing it off for years. Farley Granger appears in the film. He was fifty-five at the time of filming.

Farley Granger was my favorite actor when I discovered him as a teenager. He’s best known for his films with Hitchcock, Rope and Strangers on a Train. Outside of those films, he’s not well known, but I adored him; he was deeply uncomfortable with having fans.

I read his autobiography, Include Me Out, the summer before college, when I was eighteen, desperate, and closeted. In a chapter titled “Sex, Sex, Sex, Sex…”, he details the night that he lost his virginity. He begins, “I was thinking about sex all the time. I was twenty and still a virgin.” I also thought about sex constantly, and at the time, I compared myself to that number: twenty. Would I still be closeted, still a virgin, when I was twenty? While in the Navy, Granger was stationed in Honolulu. A friend of his found an escort service for Granger, and he met with “an absolutely ravishing young Hawaiian woman” at night in the backyard of a massive estate. He swam naked in the pool until she arrived. When she did, she complimented his body. They talked for a while, and he says she was well-educated. He says when they began, she made him take his time; she slowed him down. They made love twice, he says. He fell asleep, and when he woke up, she was gone. Still nighttime, Granger went to get his clothes but found a man sitting at the bar by the pool. He complimented Granger’s body too, and they also sat and talked. The man was a lieutenant commander in the Navy, and he was scheduled to deploy the next day. Suddenly, he pulled Granger into his arms, and Granger resisted until he realized how excited he was. Granger says they made love for hours. He never saw the lieutenant after that night.

The night I finished “Sex, Sex, Sex, Sex…,” my parents were out of town, and I snuck into our neighborhood’s pool after it had closed. As I removed my shirt, I ran my fingers along the crests and valleys of my form, my newly bursting shoulders, and the molded lines of my obliques. Like a stream, muscles flowed down the length of me, the heavenly core in my chest thrusting, heaving, sighing; I was nervous. In the cool darkness, I did laps trying to replicate what had worked for Farley. I’m not a good swimmer.

I sometimes wonder—I used to wonder more often—what would’ve happened if I had downloaded Grindr the night I read that chapter, if I had been brave enough. I think of the anticipation that may have tightened my chest, the deep breaths I may have taken as my lungs worked to still my shaking frame. I think of lips meeting my skin, the neck I may have kissed, the back I may have held, the arms that may have held me.

When I was eighteen, I thought about Granger’s chapter all the time. When I read the chapter now, it feels too clean, too tidy. Granger’s sex feels like a Hollywood sex scene, indescribably romantic and indistinct, quick to pan away to blowing curtains. He had sex with a woman and a man. How did he have sex with that man? Did they fuck? How did they fuck? Sex, sex, sex, sex. Four times. Is that how many times Granger came that night? What did he actually do? What is making love? I’ve had sex and loved the man I had sex with, but I don’t know if I’ve made love.

When I finally watched The Prowler, Granger looked nearly unrecognizable to me. I suppose he doesn’t look that old; he was only fifty-five. But he certainly doesn’t look the same as in his Hitchcock films or how I imagine him swimming in that Honolulu pool. His hair is grey. Granger only appears early in The Prowler for a couple short scenes then disappears until the Final Girl’s confrontation with the killer. The killer rips off his mask, revealing himself to be Granger. He wrestles a shotgun from the Final Girl and shoots himself. His face explodes in chunks. Unrecognizable.

Granger doesn’t write about The Prowler in Include Me Out. I wonder if he only did the movie for money. Or as a favor. Was he embarrassed by the film? When I was younger, I stopped reading Include Me Out about a third of the way through because I couldn’t stand the thought of Granger growing old. Now, I’ve seen The Prowler, confronted his aging face, and finished his memoir, and I can only think, at least he still had his hair at fifty-five.

Thesis 3: Slashers scrutinize the body, each cut incisive, the careful dissection a confession of imperfect flesh and muscle. My mirror is a screen; fragile glass in harsh light reflects the uneven lines and irregular outline of my jaw, shoulders, and abdomen. Hairs and moles are little monsters forming the derelict landscape of my skin.

~

Theatrical release poster

Theatrical release poster

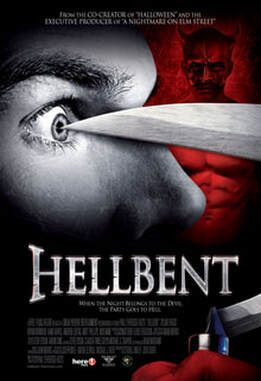

Hellbent (2004)

Dir. Paul Etheredge

I saw Hellbent for the first time and the second time and the third time, at home, alone.

Advertised as the first ever gay slasher, Hellbent is a cheaply made, incredibly silly film. The experience of watching it, especially early in the film, is that of unending eye-rolls at its truly cringe-inducing, ever-increasing series of ridiculous antics. It begins with a scene of two guys making out in a car filled with balloons—“they’re for my mom,” one of them says inexplicably—that ends when one of the men, while receiving a fellatio-adjacent foot rub, is decapitated. Hellbent only gets wilder from there and grows more charming. I care about the main character, and of course, I’m also attracted to him. I compare myself to him: a handsome eyepatch-wearing Final Boy.

In the film, the main characters dress up for the West Hollywood Halloween Carnival. They wear cop, cowboy, biker, and leather daddy costumes. In a scholarly piece on Hellbent, the author argues that the hypermasculine costumes act both as parody and eroticization of heterosexual hypermasculinity. That feels true. The dichotomous nature of the perfectly bodied gay men of Hellbent evokes the crippling envy I’ve felt throughout my life: both desire and identification.

I remember going to see films in the theater—forgettable films like I Am Number Four and Sanctum—and leaving distraught and confused, those emotions lingering with me long after I’d left the theater. The men onscreen were supposed to be my age, but their broad musculature didn’t resemble my short, thin frame. I wanted to be them, to have their masculine figures, stone jaws and carved outlines, so I could have some chance of being with them. I couldn’t disentangle these wildly conflicting ideas.

Part of me wishes I could share Hellbent with someone, that I could laugh and holler at the screen in the company of others, as slashers are supposed to be experienced,

especially silly slashers like Hellbent. I know S would watch it if I asked, but I also know he’d cringe at how cheap it is. In some teenage fantasy, I want to hold him while I watch it, to know that I am enough, that my body is enough, to have nothing to prove. He cannot give me that.

I’ve tried to become more comfortable with the fact that I watch most movies alone, that my memories of most films are solitary ones. I’ve tried to become more comfortable with myself.

Thesis 4: Slashers recognize panic, the kind of all-consuming panic that tears through me as I run my fingers through my hair, pulling the roots, curled on the floor. I’ve lost control. I can’t remember who I am. I’m drowning, spiraling. Nothing helps. I am mistakes, hatred. I am melting, revealing the dull muscle beneath, the rickety bones. Nails scrap skin, obliterating flesh and being. There’s no rescue. I cannot stop. I can’t breathe. The balloon sacks in my chest find only arid dust. They rot and shrivel.

Dir. Paul Etheredge

I saw Hellbent for the first time and the second time and the third time, at home, alone.

Advertised as the first ever gay slasher, Hellbent is a cheaply made, incredibly silly film. The experience of watching it, especially early in the film, is that of unending eye-rolls at its truly cringe-inducing, ever-increasing series of ridiculous antics. It begins with a scene of two guys making out in a car filled with balloons—“they’re for my mom,” one of them says inexplicably—that ends when one of the men, while receiving a fellatio-adjacent foot rub, is decapitated. Hellbent only gets wilder from there and grows more charming. I care about the main character, and of course, I’m also attracted to him. I compare myself to him: a handsome eyepatch-wearing Final Boy.

In the film, the main characters dress up for the West Hollywood Halloween Carnival. They wear cop, cowboy, biker, and leather daddy costumes. In a scholarly piece on Hellbent, the author argues that the hypermasculine costumes act both as parody and eroticization of heterosexual hypermasculinity. That feels true. The dichotomous nature of the perfectly bodied gay men of Hellbent evokes the crippling envy I’ve felt throughout my life: both desire and identification.

I remember going to see films in the theater—forgettable films like I Am Number Four and Sanctum—and leaving distraught and confused, those emotions lingering with me long after I’d left the theater. The men onscreen were supposed to be my age, but their broad musculature didn’t resemble my short, thin frame. I wanted to be them, to have their masculine figures, stone jaws and carved outlines, so I could have some chance of being with them. I couldn’t disentangle these wildly conflicting ideas.

Part of me wishes I could share Hellbent with someone, that I could laugh and holler at the screen in the company of others, as slashers are supposed to be experienced,

especially silly slashers like Hellbent. I know S would watch it if I asked, but I also know he’d cringe at how cheap it is. In some teenage fantasy, I want to hold him while I watch it, to know that I am enough, that my body is enough, to have nothing to prove. He cannot give me that.

I’ve tried to become more comfortable with the fact that I watch most movies alone, that my memories of most films are solitary ones. I’ve tried to become more comfortable with myself.

Thesis 4: Slashers recognize panic, the kind of all-consuming panic that tears through me as I run my fingers through my hair, pulling the roots, curled on the floor. I’ve lost control. I can’t remember who I am. I’m drowning, spiraling. Nothing helps. I am mistakes, hatred. I am melting, revealing the dull muscle beneath, the rickety bones. Nails scrap skin, obliterating flesh and being. There’s no rescue. I cannot stop. I can’t breathe. The balloon sacks in my chest find only arid dust. They rot and shrivel.

~

Theatrical release poster

Theatrical release poster

Knife+Heart (2018)

Dir. Yann Gonzalez

I watched Knife+Heart for the first time on a rainy summer day. At the end of the film, a flashback reveals the killer’s backstory. He was in love with another boy. In the scene, the boy holds the killer in his arms and the killer cries with joy. Knife+Heart presents the flashback in black and white, evoking a deep sense of nostalgia, nodding to earlier cinemas. The score is idyllic and ethereal, a series of cascading chimes scaling with quiet intensity. S called just as the film ended that first time. He said he was thinking of me. I smiled and I wanted to cry. When we hung up, I texted him: Sorry, I just watched a movie that I really enjoyed so I’m feeling vulnerable. It was a queer horror movie and it had a sweet relationship that made me really happy to have you. I don’t know. I love you. I tried to communicate the sense of melancholy and first-love euphoria that Knife+Heart left me with. I couldn’t.

In the coda to Knife+Heart, after the flashback, the protagonist, a gay porn director named Anne, is pulled away from an angelic vison of her ex-lover, who was earlier murdered by the killer, and Anne exchanges a look with her best friend and producing partner as the pulsating score fades, and the lights dim on a stark white porn set, a manufactured heaven. The men inhabiting the Grecian set look from one face to another. The darkened set shatters a fantasy, and the characters awaken some new consciousness within themselves, their gaze into the camera challenging the viewer to follow suit.

One day, as I’m driving, I leave my body for a moment and soar far above the highway stretched before me. I’m among white billowing giants that form and reform, shift and collide in elapsed time, fluid like watercolor. An uneasy resonance shakes through me, and light pours from my chest. Clusters of shapes glitter around me as memories flood the space beneath my skin. They’re the faces of everyone I’ve ever cared for, growing in number—as my mind spins—until they extend for miles in every direction, brilliant like stars, illuminating the sky. A sun appears among them, its glow taking a familiar shape: me. I smile and embrace the sun, this me who is every me from every moment of my life, infant, toddler, teenager, adult. I embrace myself, acknowledging the constellation of my body and faults and the possibility of my being.

Then I brake, eyes back on the road.

Thesis 5: Nostalgia is the essence of the slasher. They are always looking back, searching our pasts. In looking back, slashers recontextualize our histories. They acknowledge the messiness of memory and emotion and pain. On my knees, I fumble for lost and broken pieces of a forever incomplete puzzle.

Dir. Yann Gonzalez

I watched Knife+Heart for the first time on a rainy summer day. At the end of the film, a flashback reveals the killer’s backstory. He was in love with another boy. In the scene, the boy holds the killer in his arms and the killer cries with joy. Knife+Heart presents the flashback in black and white, evoking a deep sense of nostalgia, nodding to earlier cinemas. The score is idyllic and ethereal, a series of cascading chimes scaling with quiet intensity. S called just as the film ended that first time. He said he was thinking of me. I smiled and I wanted to cry. When we hung up, I texted him: Sorry, I just watched a movie that I really enjoyed so I’m feeling vulnerable. It was a queer horror movie and it had a sweet relationship that made me really happy to have you. I don’t know. I love you. I tried to communicate the sense of melancholy and first-love euphoria that Knife+Heart left me with. I couldn’t.

In the coda to Knife+Heart, after the flashback, the protagonist, a gay porn director named Anne, is pulled away from an angelic vison of her ex-lover, who was earlier murdered by the killer, and Anne exchanges a look with her best friend and producing partner as the pulsating score fades, and the lights dim on a stark white porn set, a manufactured heaven. The men inhabiting the Grecian set look from one face to another. The darkened set shatters a fantasy, and the characters awaken some new consciousness within themselves, their gaze into the camera challenging the viewer to follow suit.

One day, as I’m driving, I leave my body for a moment and soar far above the highway stretched before me. I’m among white billowing giants that form and reform, shift and collide in elapsed time, fluid like watercolor. An uneasy resonance shakes through me, and light pours from my chest. Clusters of shapes glitter around me as memories flood the space beneath my skin. They’re the faces of everyone I’ve ever cared for, growing in number—as my mind spins—until they extend for miles in every direction, brilliant like stars, illuminating the sky. A sun appears among them, its glow taking a familiar shape: me. I smile and embrace the sun, this me who is every me from every moment of my life, infant, toddler, teenager, adult. I embrace myself, acknowledging the constellation of my body and faults and the possibility of my being.

Then I brake, eyes back on the road.

Thesis 5: Nostalgia is the essence of the slasher. They are always looking back, searching our pasts. In looking back, slashers recontextualize our histories. They acknowledge the messiness of memory and emotion and pain. On my knees, I fumble for lost and broken pieces of a forever incomplete puzzle.

Cole Brayfield is a writer, game designer, and avid horror movie fan. He lives and teaches in Indianapolis, Indiana. Find more of his work at: www.brayfieldwriting.com