Interview

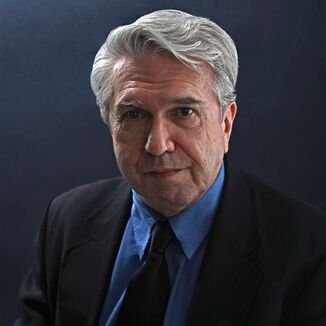

Finding Humor in Anything I Please: An Interview with James Carpenter

BY Courtney R. Hall, Daniel Hewitt, Cat Reed, Javis Sisco

October 2023

It’s not common to meet someone who brings magic to everything they touch, but James Carpenter seems to bring that special something wherever he goes. After an electric career in education, business, and information technology, including a position as an affiliated faculty member at The Wharton School, James has channeled that magic touch into writing. Larry Bensky described his first novel No Place to Pray as “the creative nexus where Faulkner, Cormac McCarthy, and Richard Pryor converge.” His second novel, Nineteen To Go, finds a way to blend the topic of vasectomies with humor using the 1950s as the backdrop, a feat that many others would not be able to accomplish. In addition to writing novels, he consistently writes short fiction, with some appearing in the Chicago Tribune's Printers Row, Fiction International, and North Dakota Quarterly. Three of his stories were nominated for the Pushcart Prize and he is a recipient of Descant's Frank O'Connor Prize.

In this interview with Glassworks, James Carpenter brings his candid humor and vulnerability to the table, all the while showing that he does have a serious bone or two in his body.

In this interview with Glassworks, James Carpenter brings his candid humor and vulnerability to the table, all the while showing that he does have a serious bone or two in his body.

Glassworks Magazine (GM): Looking into your history, you’ve had a professional career in software engineering prior to a career in writing. It can even be said that you have one foot stepping into the future and one still planted in history, with your novels being set decades in the past. Do you find it easier to write about the past despite being in a profession that works toward a better tomorrow? One would think that you would write more about “what you know,” but your professional career doesn’t seem to influence your creative work.

James Carpenter (JC): Software development, in every sense and by every definition, is writing, writing whose goal is to model the real world, to abstract essences from shared cultural, economic, and political experience and to garner insights from those experiences that can be used to evolve new, more efficient ways of doing things—just as natural writing does. So, I’ve never not been writing what I know. Just writing differently, but now with a more moral intent. Which I realize challenges your question about software working toward a better tomorrow. I’m far from a luddite, but experience doesn’t bode well for what we’ll do next with digital technologies. Think Facebook, Twitter, data mining, targeted advertising, electronic surveillance, cyber warfare, weapons of war that can be guided from half a world away. I’m more hopeful that writing in natural language rather than in computer programming languages is more likely to lead to that better tomorrow.

So far as setting my stories in the past. Hey, I’m seventy-five. All I got is past. It’s what I know.

GM: As someone who stepped away from writing for decades, what was it like to step back into the writing world? Can you describe the publishing process you went through upon returning?

JC: I earned a master’s degree in my 50s. My capstone project was a complex software system that generated poetry. My thesis: computationally generated poetry can successfully compete with traditionally composed human poetry. The most difficult part of the project lay not in how to build the system, but in how to test it. What my advisors and I finally landed on was simply to submit the system’s output to literary journals. If these journals accepted the work, then it was clearly competitive. It was. I published somewhere around three dozen of the system’s poems, confirming my thesis. Which is probably pretty interesting as a technical accomplishment. But the more interesting result for me personally was that I was never emotionally connected to either acceptances or rejections. Pleased, of course, when a journal accepted one of the software’s poems, in that each acceptance further confirmed my thesis, but not dejected if that journal declined. The yeas and nays were simply data points in an analysis of a system’s output. No deep emotional investment.

When I started writing the old-fashioned way again, I adopted that same approach. If a piece finds a home, fine. If not, just keep looking. By detaching from the results of the process, I was able to shed the emotional excesses that led me to stop writing in the first place.

Upon first returning to writing, the publishing process was much as it was when I left. Paper submissions. SASEs. Paper rejections. Only here and there, a few electronic submissions. So I was able to ease into the process without having to adjust to entirely different submission mechanisms than what I knew. And then just adapt along with everyone else as new processes emerged.

On the other hand, the tools of composition had radically evolved for the better. For example, I no longer had to make sure I always had a spare typewriter ribbon at hand.

James Carpenter (JC): Software development, in every sense and by every definition, is writing, writing whose goal is to model the real world, to abstract essences from shared cultural, economic, and political experience and to garner insights from those experiences that can be used to evolve new, more efficient ways of doing things—just as natural writing does. So, I’ve never not been writing what I know. Just writing differently, but now with a more moral intent. Which I realize challenges your question about software working toward a better tomorrow. I’m far from a luddite, but experience doesn’t bode well for what we’ll do next with digital technologies. Think Facebook, Twitter, data mining, targeted advertising, electronic surveillance, cyber warfare, weapons of war that can be guided from half a world away. I’m more hopeful that writing in natural language rather than in computer programming languages is more likely to lead to that better tomorrow.

So far as setting my stories in the past. Hey, I’m seventy-five. All I got is past. It’s what I know.

GM: As someone who stepped away from writing for decades, what was it like to step back into the writing world? Can you describe the publishing process you went through upon returning?

JC: I earned a master’s degree in my 50s. My capstone project was a complex software system that generated poetry. My thesis: computationally generated poetry can successfully compete with traditionally composed human poetry. The most difficult part of the project lay not in how to build the system, but in how to test it. What my advisors and I finally landed on was simply to submit the system’s output to literary journals. If these journals accepted the work, then it was clearly competitive. It was. I published somewhere around three dozen of the system’s poems, confirming my thesis. Which is probably pretty interesting as a technical accomplishment. But the more interesting result for me personally was that I was never emotionally connected to either acceptances or rejections. Pleased, of course, when a journal accepted one of the software’s poems, in that each acceptance further confirmed my thesis, but not dejected if that journal declined. The yeas and nays were simply data points in an analysis of a system’s output. No deep emotional investment.

When I started writing the old-fashioned way again, I adopted that same approach. If a piece finds a home, fine. If not, just keep looking. By detaching from the results of the process, I was able to shed the emotional excesses that led me to stop writing in the first place.

Upon first returning to writing, the publishing process was much as it was when I left. Paper submissions. SASEs. Paper rejections. Only here and there, a few electronic submissions. So I was able to ease into the process without having to adjust to entirely different submission mechanisms than what I knew. And then just adapt along with everyone else as new processes emerged.

On the other hand, the tools of composition had radically evolved for the better. For example, I no longer had to make sure I always had a spare typewriter ribbon at hand.

"If a piece finds a home, fine. If not, just keep looking. By detaching from the results of the process, I was able to shed the emotional excesses that led me to stop writing in the first place." |

GM: In your novel Nineteen to Go, the story is set in the 1950s when conversations about birth control were just beginning in America. Is there a connection between the real world conversations on birth control and the choice to have your characters talk about vasectomies? Can you explain your reasoning for choosing an older time period for what many consider a more contemporary topic?

JC: Access to birth control in America has been fraught with controversy for at least two hundred years. The only sense in which contraception is a contemporary topic is that it has been a contemporary topic through all that time. But that’s just a distraction. Here’s the real skinny on the story. |

I used to combat writer’s block by composing humorous little vignettes. One of these was based on a real story I heard from a colleague back in the ‘70s. He and a friend really did get drunk one night and go to the emergency room to get vasectomies. (And they really did ask for“ball-ectomies.”) I’d show these short pieces to my wife, who eventually said that that was the kind of writing I should do. So I turned that flash piece into a novel. (After I published it, she said she meant I should write lots of vignettes, not one long and funny piece.)

The most important reason I set the story in the ‘50s was that today you don’t check into a hospital for the procedure. The doctor just does it in their office. No ER, no hospital. No hospital, no story.

Other reasons: Setting a story in the ‘50s means you don’t have to deal with cell phones. Plus you can throw out copious cultural references that you can hint are relevant to the time and people won’t know if that’s really true or if you’re just messing with them.

The most important reason I set the story in the ‘50s was that today you don’t check into a hospital for the procedure. The doctor just does it in their office. No ER, no hospital. No hospital, no story.

Other reasons: Setting a story in the ‘50s means you don’t have to deal with cell phones. Plus you can throw out copious cultural references that you can hint are relevant to the time and people won’t know if that’s really true or if you’re just messing with them.

GM: Looking at your book No Place to Pray, which is set in the 1960s, the setting feels realistic but is otherwise fictional. Why did you decide to create this historical but fictionalized county instead of choosing a setting that previously already existed? What about the traditional tropes and images of the south drew you to them and inspired your work?

JC: First, a bit of aesthetics. My view about narration is that the story doesn’t exist until someone reads it, that it is actually the reader who creates the story. The author’s responsibility is to build a scaffolding upon which the story can be built. Multiple stories actually, since each reader will drape that scaffolding with images from within their own experience. To that end, though I try to write in images, I deliberately leave a lot out. That is not to say that I try for some kind of minimalism. Obviously, I don’t. But I try for that space where the reader enters into the creative process. For example, even though No Place to Pray deals with themes of race, I don’t identify most characters’ race. I leave that up to you. Only when it matters in some significant way to plot or theme do I indicate race. Ask yourself, what color is the preacher baptizing converts in the early chapters? What color is Marilyn? Rister? The boy who fills Edna’s gas tank? The men who deliver the materials for Edna’s deck? More importantly, what makes you think so?

Fictionalizing the parish and county where the action occurs is my maintaining allegiance to this compositional principle. The reader can make of it anything that feels right to them. Populate these places’ scenery, their inhabitants, their places of commerce. If I should set my story in Alabama or Kentucky or West Virginia, the reader will make immediate assumptions about those places and I will have betrayed my aesthetic.

So far as the tropes of the south are concerned, only those passages which are set in Tabernacle Parish are recognizably southern. And that only because Louisiana is the only state divided into parishes rather than counties. Brigard County, where most of the action occurs, is Appalachian, as am I. So I wasn’t actually inspired by some imagined, peregrine country. I just wrote “what I know.”

JC: First, a bit of aesthetics. My view about narration is that the story doesn’t exist until someone reads it, that it is actually the reader who creates the story. The author’s responsibility is to build a scaffolding upon which the story can be built. Multiple stories actually, since each reader will drape that scaffolding with images from within their own experience. To that end, though I try to write in images, I deliberately leave a lot out. That is not to say that I try for some kind of minimalism. Obviously, I don’t. But I try for that space where the reader enters into the creative process. For example, even though No Place to Pray deals with themes of race, I don’t identify most characters’ race. I leave that up to you. Only when it matters in some significant way to plot or theme do I indicate race. Ask yourself, what color is the preacher baptizing converts in the early chapters? What color is Marilyn? Rister? The boy who fills Edna’s gas tank? The men who deliver the materials for Edna’s deck? More importantly, what makes you think so?

Fictionalizing the parish and county where the action occurs is my maintaining allegiance to this compositional principle. The reader can make of it anything that feels right to them. Populate these places’ scenery, their inhabitants, their places of commerce. If I should set my story in Alabama or Kentucky or West Virginia, the reader will make immediate assumptions about those places and I will have betrayed my aesthetic.

So far as the tropes of the south are concerned, only those passages which are set in Tabernacle Parish are recognizably southern. And that only because Louisiana is the only state divided into parishes rather than counties. Brigard County, where most of the action occurs, is Appalachian, as am I. So I wasn’t actually inspired by some imagined, peregrine country. I just wrote “what I know.”

"My view about narration is that the story doesn’t exist until someone reads it, that it is actually the reader who creates the story. The author’s responsibility is to build a scaffolding upon which the story can be built." |

GM: Race is a key topic in your novel No Place to Pray, and during your interview with Jackie Mantey you mention doing a considerable amount of research into the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s when writing this book. Did any of your research come out of firsthand experience, either yours or of people close to you?

JC: I have a friend who was a civil rights activist in the ‘60s. |

He was beaten and jailed multiple times while advocating and protesting for social and political justice.

He was extraordinarily generous with his time. Talking with him was one of the most unsettling experiences of my life, so brutal were the stories he shared. At one point I asked him how he ever mustered the courage to continue to engage when he was clearly in serious danger. He seemed surprised by the question and simply told me, “We didn’t think about that. We did it because it was the right thing to do.”

I should add that he was equally generous with his criticisms of my work. At times, he would be quite put out with my characterizations and let me know very clearly what he saw as unconscious racism in my work. Every white person (and especially every white writer) should be blessed with such a friend.

I also spent quite a bit of time with other Black friends, discussing everything from the odd way we would be treated as a mixed-race party in restaurants to the subtle polysemies of racial slurs. Things unapparent to me until they pointed them out. And then so obvious that I was embarrassed to have missed them.

And personal experiences as well, too many to relate here. But I’ll share one. In Cleveland during the summer of 1968, a friend and I returned home to find our housemates tending to a young woman covered in blood whom they had seen being beaten by other women along a nearby main thoroughfare. Turned out that this white woman was married to a Black man and they had been visiting friends in an ethnic Italian neighborhood. When they left the apartment, they were attacked: she by the women who dragged her to the main street and the husband by a group of men. The woman was hysterical over what she feared had happened to him. One of the guys and I went looking for him. Off on a side street, we saw a group of people and a police squad car. We went over and I asked one of the officers if a Black man had been involved in the incident. Immediately the group of men became irate, surrounding my friend and me and making threats. I walked to the police car and grabbed hold of the door, saying to the officer that it looked like my friend and I needed them to give us a ride out of there. His response? “You should have thought of that before you came down the street.”

He was extraordinarily generous with his time. Talking with him was one of the most unsettling experiences of my life, so brutal were the stories he shared. At one point I asked him how he ever mustered the courage to continue to engage when he was clearly in serious danger. He seemed surprised by the question and simply told me, “We didn’t think about that. We did it because it was the right thing to do.”

I should add that he was equally generous with his criticisms of my work. At times, he would be quite put out with my characterizations and let me know very clearly what he saw as unconscious racism in my work. Every white person (and especially every white writer) should be blessed with such a friend.

I also spent quite a bit of time with other Black friends, discussing everything from the odd way we would be treated as a mixed-race party in restaurants to the subtle polysemies of racial slurs. Things unapparent to me until they pointed them out. And then so obvious that I was embarrassed to have missed them.

And personal experiences as well, too many to relate here. But I’ll share one. In Cleveland during the summer of 1968, a friend and I returned home to find our housemates tending to a young woman covered in blood whom they had seen being beaten by other women along a nearby main thoroughfare. Turned out that this white woman was married to a Black man and they had been visiting friends in an ethnic Italian neighborhood. When they left the apartment, they were attacked: she by the women who dragged her to the main street and the husband by a group of men. The woman was hysterical over what she feared had happened to him. One of the guys and I went looking for him. Off on a side street, we saw a group of people and a police squad car. We went over and I asked one of the officers if a Black man had been involved in the incident. Immediately the group of men became irate, surrounding my friend and me and making threats. I walked to the police car and grabbed hold of the door, saying to the officer that it looked like my friend and I needed them to give us a ride out of there. His response? “You should have thought of that before you came down the street.”

|

And then they drove off. As soon as their car turned out of sight, the men, now a mob, began to chase us, screaming at us that we were n***er-lovers and threat- ening to kill us. We escaped only by running into the heavily trafficked street and dodging cars.

|

"When I related it to my civil rights-activist friend, his sole remark was to ask if I’d thought back then that I could trust the police. When I said I had, he just shook his head." |

Civil, sedate conversations about racism, both personal and institutional, can never uncover its truly heinous and evil motives. Knowing that in this moment you could die of it, in a savage, violent way, is far more educational.

As an addendum to this experience: When I related it to my civil rights-activist friend, his sole remark was to ask if I’d thought back then that I could trust the police. When I said I had, he just shook his head.

GM: In that same interview, you mention that you stepped away from writing in your twenties because writing became synonymous with drinking. Being that alcoholism is a driving theme in your novel No Place to Pray, how did your personal experience influence your development of your main character, Harmon?

JC: Alcoholism will take you to places you absolutely do not want to go. Dark and threatening places. Humiliating places. At the same time it’s a tremendous amount of work, requiring sustained, determined effort. Not getting caught stealing is hard work. Just keeping track of all the lies is a Herculean task in itself. Not to mention talking someone out of slitting your throat when he has you down on the ground with a knee on your chest and a knife at your throat and you have no idea whatsoever what it was you did to so enrage him.

I tried to capture all that despair and determination in Harmon. Perhaps the clearest distillation of that complex is the scene where Harmon is thrown out of the bar. You may think you’ve been asked to leave a place, but until you’ve been dragged through the kitchen and thrown out the back door because the establishment doesn’t want the public to see that they cater to degenerates like you, you haven’t.

GM: Your novels include heavy themes and elements such as questioning one’s spirituality, race, class, etc. However, throughout your work you approach these serious topics with a dark humor. Why the choice to add humor when, given the time and place, some readers may not find the humor in it themselves?

JC: Because some readers will.

GM: Both of your novels include themes of redemption and growth. How does your perception of your own humanity and spirituality reflect in the development of your characters and their development of self?

JC: I’ve come close to dying several times, bad accidents, serious injuries, life-threatening illnesses. Getting through these, I held to the mantra: what do I need to do in this moment to get to the next? Where do I find the will? Among the several things I want to convey through Harmon is this instinct to survive.

As an addendum to this experience: When I related it to my civil rights-activist friend, his sole remark was to ask if I’d thought back then that I could trust the police. When I said I had, he just shook his head.

GM: In that same interview, you mention that you stepped away from writing in your twenties because writing became synonymous with drinking. Being that alcoholism is a driving theme in your novel No Place to Pray, how did your personal experience influence your development of your main character, Harmon?

JC: Alcoholism will take you to places you absolutely do not want to go. Dark and threatening places. Humiliating places. At the same time it’s a tremendous amount of work, requiring sustained, determined effort. Not getting caught stealing is hard work. Just keeping track of all the lies is a Herculean task in itself. Not to mention talking someone out of slitting your throat when he has you down on the ground with a knee on your chest and a knife at your throat and you have no idea whatsoever what it was you did to so enrage him.

I tried to capture all that despair and determination in Harmon. Perhaps the clearest distillation of that complex is the scene where Harmon is thrown out of the bar. You may think you’ve been asked to leave a place, but until you’ve been dragged through the kitchen and thrown out the back door because the establishment doesn’t want the public to see that they cater to degenerates like you, you haven’t.

GM: Your novels include heavy themes and elements such as questioning one’s spirituality, race, class, etc. However, throughout your work you approach these serious topics with a dark humor. Why the choice to add humor when, given the time and place, some readers may not find the humor in it themselves?

JC: Because some readers will.

GM: Both of your novels include themes of redemption and growth. How does your perception of your own humanity and spirituality reflect in the development of your characters and their development of self?

JC: I’ve come close to dying several times, bad accidents, serious injuries, life-threatening illnesses. Getting through these, I held to the mantra: what do I need to do in this moment to get to the next? Where do I find the will? Among the several things I want to convey through Harmon is this instinct to survive.

"But to say that the body and spirit collaborate to endure, whether or not that is illusionary and whether or not there exists a place to pray, is to acknowledge a fact. In spite of the pain, people don’t want to die." |

The most important line in No Place to Pray appears in the passage showing Harmon in the morning after he barely escapes from his burning cabin. “Before him lay ashes.”

His response is to get up and move. But Harmon is dying and there’s not a thing he can do about it. He is not going to survive this last bed of ashes. Yet he gets up. I don’t write this with any aphoristic or platitudinous intention—there is that risk. But to say that the body and spirit collaborate to endure, whether or not that is illusionary and whether or not there exists a place to pray, is to acknowledge a fact. In spite of the pain, people don’t want to die. |

Read more about Carpenter's work on his website