Interview

Serving Time and Stories: An interview with Jayne M. Thompson

BY Mickey Bratton, Connor Buckmaster, & Brianna McCray

July 2020

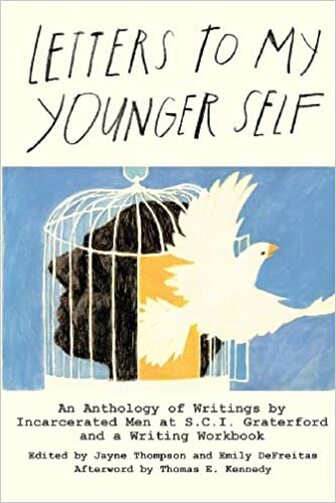

Before reading the anthology Letters to My Younger Self: An Anthology of Writings by Incarcerated Men at S.C.I. Graterford and a Writing Workbook, one might anticipate coming to understand why these men are criminals. But Jayne Thompson, Assistant Teaching Professor of English and director of Chester Writers House, a non-profit writing center in Chester, PA, shows us so much more than their crimes. For eight years, Thompson has been volunteering to teach creative writing to men at S.C.I. Graterford, many of whom are serving life sentences. Published in June 2014 by Serving House Books, Letters to My Younger Self is a collection of writings from her first class at Graterford. In this anthology, she captures readers by uncovering the voices of these men from the confinements of their cages. The raw confessions shared in Letters to My Younger Self force readers to shift their perceptions from preconceived notions and ignorance to an empathetic common ground. Thompson’s findings, explicit and heart-warming, can bring communities together to start believing in a humanity constructed by the art of compassion, forgiveness, and the nature of love. No profits are derived from Letters to My Younger Self, and all proceeds go toward printing and distributing free copies to young people in the juvenile facilities and high schools where Thompson teaches as a volunteer.

Glassworks Magazine (GM): This anthology came from your work in the 2011 Prison Literacy Program Creative Writing Class at Graterford Prison in Pennsylvania. There, you worked with incarcerated men, many of whom had been there since their youth. Can you describe how you started working with these men, and why you felt their work needed to be published?

Jayne Thompson (JT): Over a decade ago, a sociology professor at Widener University asked me to teach poetry writing at the prison with him. I was intrigued. The course was part of the Inside-Out Prison Program run by Lori Pompa from Temple University. I signed up to take the required training, a full week of workshops inside and outside of the prison. We were taught how to run classes in the prison, and our inside trainers were incarcerated men. The training was filled with books by activists like bell hooks, Angela Davis, and Paulo Freire. Our focus was to learn how to teach classes in which we were to decenter authority and become learners, ourselves, inside our own classrooms. To say that I loved this training is an understatement. Pompa is an extremely talented teacher, and so were the incarcerated men who trained me. At the prison I met Paul Perry, the man responsible for the idea behind Inside-Out. He asked me to teach a creative writing workshop at Graterford. That first class lasted three years! After about a year, I had pages and pages of the men’s work, and I started to realize that the men had voice galore. I started telling them stories about my experiences in the Chester High School classroom where I taught just one class a day for five days a week. I worried so much about these kids, and I worried about the kids I was meeting when I heard the cases of juvenile offenders in Chester for the Youth Panel, a program that helps children learn from their mistakes through dialogue. We have the power to expunge their records if they complete the program successfully. The stories I heard from these children kept me up at night, as did my experience at Chester High. I felt like I could do nothing concrete to help these children. The men at Graterford said the same thing. They felt that they had let the young people down by being in prison instead of the community. I asked them to write to these kids. The men began creating pieces, and I soon realized that we needed to publish the book and distribute it for free to children in schools and juvenile detention centers. The men performed social work from behind bars. Their commitment to the project is the biggest example of empathy I have ever witnessed. They longed to tell children of their own mistakes and showed tremendous empathy for young people they had never met.

GM: In the introduction for Letters to My Younger Self, you describe how this anthology provides a way for young juveniles to “hear [the Graterford guys’] stories and wisdom,” a way to learn from their mistakes. However, you mention that their works speak to us all. Can you explain how this touches not only the youth in troubled communities, but all of us?

JT: The men have experienced so much trauma in their lives. There is not one man who I have met at the prison who did not experience trauma, even if it was just the trauma of arrest, sentencing, and incarceration. They could give in to despair, and many unfortunately do. These men have become altruistic in their suffering. I have seen them speak about the release from prison of other men with true joy—not a trace of jealousy. I have seen them help one another with assignments and give one another advice with gentleness and respect. When Chris read his piece about being raped by his brother, the men expressed themselves with empathy and wisdom, and I was so thankful for that because I was struck dumb by the piece’s honesty and beauty—and its sadness—for at least a minute, which is too long to remain silent. The men jumped to my aid. As a group we decided that Chris’s piece should be the first in the book because he was the first to share—and so very brave. We can all learn from this kind of courage. I know I have.

GM: Was it surprising for you to witness the humanity and vulnerability within the works of these men?

JT: I was often surprised by the men’s ability to talk about parts of their lives that show them as conflicted, vulnerable, even weak. They taught me how to find the truth that lies deep inside. I had another goal in assigning the Graterford men to write to and about their younger selves. I wanted them to use narrative to create an object, with the younger self as the subject. Perhaps the men, in polishing the object, could step outside of themselves and look at the subject—finding empathy for the young man in the story, for themselves. Gandhi states: “Power is of two kinds. One is obtained by the fear of punishment and the other by acts of love. Power based on love is a thousand times more effective and permanent than the one derived from fear of punishment.” They told their stories as “acts of love.”

I have been blessed by the time I spent at Graterford with these men. I wonder if I will ever again experience people who are so empathic, so altruistic, and so brave. Not many people expect to hear incarcerated people spoken of in terms of empathy, altruism, and bravery, but I can tell you that it exists in the prison, which is perhaps the biggest tribute I can give to the men. In some of life’s most difficult circumstances, when so much has been taken, there are some who become stronger, better, kinder, braver—and I am so glad that I know them. We named our group, “Humanitarians at the Grate.” It is so fitting.

GM: Through your work with the men in S.C.I. Graterford, you’ve described writing as “an avenue to freedom.” Can you explain how you came to this understanding, and how writing functions in this way?

JT: Reading and writing has saved my life. I grew up in challenging circumstances. I found books at the public library, and they saved me in three ways: my skills improved, making me a stronger student; my ability to empathize with others improved, making me more understanding of my own and others’ circumstances; and I began to look at the world with writerly eyes, making me want to write and share this love of writing with others. About 10 years ago, I wrote a novel that was semi-autobiographical. I wrote about a girl, May, who experienced much of what I experienced. The process of narrating events allowed me to see my life differently. I had empathy for May—maybe I could have empathy for Jayne.

I heard a story at a conference once about a veteran who had determined to commit suicide. He wrote a note to his loved ones and left his home. Something drew him back to the house. He saw the note on the table, and said aloud, “That poor guy” about himself. He decided not to commit suicide. So, literally, writing can save your life. But it can also be an avenue to freedom in other ways. One time in the Graterford class, one of the men asked me why I write. I thought for a moment and said, “I like that sinking down into another level of consciousness that writing brings. Time is not an issue. Just me and my ideas and my words—nothing else matters—time, ideas, and words are not even conscious thoughts. It is worth all the hard work for those moments.” One of the guys replied, “That’s it. That’s exactly it. I couldn’t survive in here without those moments.” One time the men and I started walking down the hallway together like we had just left a college classroom. I thought the guards would kick me out for sure. I am supposed to wait for my guard escort; the men are supposed to line up to be frisked. But that night, we weren’t in prison. Reading and writing had freed us—until we heard, “Stop right there!” All of us were shocked that it had happened, but secretly pleased that we had flown out of the prison with our minds.

Jayne Thompson (JT): Over a decade ago, a sociology professor at Widener University asked me to teach poetry writing at the prison with him. I was intrigued. The course was part of the Inside-Out Prison Program run by Lori Pompa from Temple University. I signed up to take the required training, a full week of workshops inside and outside of the prison. We were taught how to run classes in the prison, and our inside trainers were incarcerated men. The training was filled with books by activists like bell hooks, Angela Davis, and Paulo Freire. Our focus was to learn how to teach classes in which we were to decenter authority and become learners, ourselves, inside our own classrooms. To say that I loved this training is an understatement. Pompa is an extremely talented teacher, and so were the incarcerated men who trained me. At the prison I met Paul Perry, the man responsible for the idea behind Inside-Out. He asked me to teach a creative writing workshop at Graterford. That first class lasted three years! After about a year, I had pages and pages of the men’s work, and I started to realize that the men had voice galore. I started telling them stories about my experiences in the Chester High School classroom where I taught just one class a day for five days a week. I worried so much about these kids, and I worried about the kids I was meeting when I heard the cases of juvenile offenders in Chester for the Youth Panel, a program that helps children learn from their mistakes through dialogue. We have the power to expunge their records if they complete the program successfully. The stories I heard from these children kept me up at night, as did my experience at Chester High. I felt like I could do nothing concrete to help these children. The men at Graterford said the same thing. They felt that they had let the young people down by being in prison instead of the community. I asked them to write to these kids. The men began creating pieces, and I soon realized that we needed to publish the book and distribute it for free to children in schools and juvenile detention centers. The men performed social work from behind bars. Their commitment to the project is the biggest example of empathy I have ever witnessed. They longed to tell children of their own mistakes and showed tremendous empathy for young people they had never met.

GM: In the introduction for Letters to My Younger Self, you describe how this anthology provides a way for young juveniles to “hear [the Graterford guys’] stories and wisdom,” a way to learn from their mistakes. However, you mention that their works speak to us all. Can you explain how this touches not only the youth in troubled communities, but all of us?

JT: The men have experienced so much trauma in their lives. There is not one man who I have met at the prison who did not experience trauma, even if it was just the trauma of arrest, sentencing, and incarceration. They could give in to despair, and many unfortunately do. These men have become altruistic in their suffering. I have seen them speak about the release from prison of other men with true joy—not a trace of jealousy. I have seen them help one another with assignments and give one another advice with gentleness and respect. When Chris read his piece about being raped by his brother, the men expressed themselves with empathy and wisdom, and I was so thankful for that because I was struck dumb by the piece’s honesty and beauty—and its sadness—for at least a minute, which is too long to remain silent. The men jumped to my aid. As a group we decided that Chris’s piece should be the first in the book because he was the first to share—and so very brave. We can all learn from this kind of courage. I know I have.

GM: Was it surprising for you to witness the humanity and vulnerability within the works of these men?

JT: I was often surprised by the men’s ability to talk about parts of their lives that show them as conflicted, vulnerable, even weak. They taught me how to find the truth that lies deep inside. I had another goal in assigning the Graterford men to write to and about their younger selves. I wanted them to use narrative to create an object, with the younger self as the subject. Perhaps the men, in polishing the object, could step outside of themselves and look at the subject—finding empathy for the young man in the story, for themselves. Gandhi states: “Power is of two kinds. One is obtained by the fear of punishment and the other by acts of love. Power based on love is a thousand times more effective and permanent than the one derived from fear of punishment.” They told their stories as “acts of love.”

I have been blessed by the time I spent at Graterford with these men. I wonder if I will ever again experience people who are so empathic, so altruistic, and so brave. Not many people expect to hear incarcerated people spoken of in terms of empathy, altruism, and bravery, but I can tell you that it exists in the prison, which is perhaps the biggest tribute I can give to the men. In some of life’s most difficult circumstances, when so much has been taken, there are some who become stronger, better, kinder, braver—and I am so glad that I know them. We named our group, “Humanitarians at the Grate.” It is so fitting.

GM: Through your work with the men in S.C.I. Graterford, you’ve described writing as “an avenue to freedom.” Can you explain how you came to this understanding, and how writing functions in this way?

JT: Reading and writing has saved my life. I grew up in challenging circumstances. I found books at the public library, and they saved me in three ways: my skills improved, making me a stronger student; my ability to empathize with others improved, making me more understanding of my own and others’ circumstances; and I began to look at the world with writerly eyes, making me want to write and share this love of writing with others. About 10 years ago, I wrote a novel that was semi-autobiographical. I wrote about a girl, May, who experienced much of what I experienced. The process of narrating events allowed me to see my life differently. I had empathy for May—maybe I could have empathy for Jayne.

I heard a story at a conference once about a veteran who had determined to commit suicide. He wrote a note to his loved ones and left his home. Something drew him back to the house. He saw the note on the table, and said aloud, “That poor guy” about himself. He decided not to commit suicide. So, literally, writing can save your life. But it can also be an avenue to freedom in other ways. One time in the Graterford class, one of the men asked me why I write. I thought for a moment and said, “I like that sinking down into another level of consciousness that writing brings. Time is not an issue. Just me and my ideas and my words—nothing else matters—time, ideas, and words are not even conscious thoughts. It is worth all the hard work for those moments.” One of the guys replied, “That’s it. That’s exactly it. I couldn’t survive in here without those moments.” One time the men and I started walking down the hallway together like we had just left a college classroom. I thought the guards would kick me out for sure. I am supposed to wait for my guard escort; the men are supposed to line up to be frisked. But that night, we weren’t in prison. Reading and writing had freed us—until we heard, “Stop right there!” All of us were shocked that it had happened, but secretly pleased that we had flown out of the prison with our minds.

|

GM: How did your experiences teaching these men and collating their works affect your professional work as a writer and teacher?

|

"Literally, writing can save your life. But it can also be an avenue to freedom in other ways." |

JT: I am constantly pulling from experiences in the prison to underscore a point I am making. My time with these men was so enriching that I want my students to benefit from my experiences. This semester alone, I have a number of students who are working on issues of incarceration in their research papers and other work. Just last week I took four students to a juvenile detention center where they ran peace circles. A number of them have volunteered to help me begin a writing center at SCI Chester, the prison about five minutes away from our campus where I now teach writing workshops. We want to take our work to another level by opening a writing center and training incarcerated men to work in it along with us. In addition, I receive calls often to share the work publicly. This sharing has made me a better speaker, teacher, and writer. I like being an ambassador of the men’s work. I loved working on the book with my student, Emily DeFreitas. Our collaboration is one of my fondest teaching memories.

In addition, I have written creative nonfiction pieces that I have published. I never knew that I liked creative nonfiction! Right now, I am working on a novel that is set in a prison, so my life has a writer has certainly expanded with the experience.

GM: What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

JT: I want people to say NO to the continuation of our current prison system. I subscribe to an idea that is described very well by New Tactics in Human Rights, a Program of the Center for Victims of Torture, which states that we can “change deeply held cultural narratives and open new space for our stories” with “Powerful narratives and effective story-based strategy [that] change cultural norms and [create] a space for new stories, ideas, and norms to flourish. [Center for Story-based Strategy] believes there is a moment they term a ‘psychic break’ that is the process or moment of realization whereby a deeply held dominant culture narrative comes into question, oftentimes stemming from a revelation that a system, event, or course of events is out of alignment with core values.”

Indeed, the Center for Story-based Strategy believes that “stories are embedded with power – the power to explain and justify the status quo as well as the power to make change imaginable and urgent. A narrative analysis of power encourages us to ask: Which stories define cultural norms? Where did these stories come from? Whose stories were ignored or erased to create these norms? And, most urgently, what new stories can we tell to help create the world we desire?”

Certainly, the world many in the US desire is one without the injustices we are seeing in our justice system. The United States’ incarceration rates are the highest in the world. According to the Sentencing Project, “There are 2.2 million people in the nation’s prisons and jails—a 500% increase over the last 40 years. Changes in law and policy, not changes in crime rates, explain most of this increase. The results are overcrowding in prisons and fiscal burdens on states, despite increasing evidence that large-scale incarceration is not an effective means of achieving public safety.” What of these 2.2 million in US prisons and jails—and many more who are in some way involved in the court and probation systems? Some are on death row, others are serving life without parole, still others will serve their sentences and be released, though rarely will they truly rejoin mainstream America. Certainly, their voices are “othered,” marginalized, and often silenced. They are othered and silenced by the justice system, the prison system, at times by fellow prisoners, by perceptions of the incarcerated in the larger culture, sometimes even unwittingly by the free public and the people who are studying and reporting on the plight of the incarcerated, the very people who mean to remediate the injustices within the system.

I hope that readers of Letters will question the “dominant cultural narrative” and demand change.

GM: Would you consider pursuing other anthologies like this, perhaps based around women’s confinement as well? What other new ideas and projects are you working on at the moment?

JT: Yes! Since July of 2019, I have been working at SCI Chester on a post-traumatic growth curriculum that was started by a professor at Widener University, Dr. Kit Healey. She is retiring, and I am taking it over and making it based more on reading and writing. Widener University students, incarcerated men, and I [started] an anthology project in January 2020. We are all so excited and curious to see what we will create.

I recently finished working on a project that gathered women’s voices. I was inspired while traveling to Europe for the first time. In Berlin, I stood gazing at the Käthe Kollwitz sculpture "Mother with Her Dead Son." This sculpture captured the horrors of war—and spoke of women’s experiences; Kollwitz, artist and pacifist, suffered great loss in a life that spanned the World Wars. I found it difficult to leave the space. I remembered the poem that I had read years before, Muriel Rukeyser’s “Kathe Kollwitz,” two lines of which had stuck with me, “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?/The world would split open.”

I returned to my women’s writing group in Chester, PA, and I watched women’s faces as I asked them to respond to Rukeyser’s words, and their reactions showed me that I might be onto something. To gather incarcerated women’s voices, we sent out a call to prisons, and we have submissions from England, Scotland, Australia, and many US states. We formed The World Split Open Story Collaborative with six women and requested assistance from scholar, poet and performance artist Andrea Zittlau of Rostock, Germany. The public arts project that resulted is in the spirit of street literature broadsides that were popular from the 16th to 19th centuries. Whether used to bring ballads, advertisements, or news to the public, they were undeniably important in history as a means for individuals to communicate with others in public places. We believe that bringing these pieces to the public is a modern nod to the broadside’s power to inform; in this case, we are making public the stories that women too often and for too long have kept private. Indeed, if we take the pulse of the United States at the moment, we see that many individuals, especially women, are coming forward to tell of abuses, particularly sexual abuses, they have experienced. Indeed, our project focuses on much the same theme: women coming forward to tell about their lives by responding to Muriel Rukeyser’s poem. We had no idea what would be happening in the public sphere when we began our public arts project, but we are excited to be part of this movement and hope to do our part to further its momentum

In addition, I have written creative nonfiction pieces that I have published. I never knew that I liked creative nonfiction! Right now, I am working on a novel that is set in a prison, so my life has a writer has certainly expanded with the experience.

GM: What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

JT: I want people to say NO to the continuation of our current prison system. I subscribe to an idea that is described very well by New Tactics in Human Rights, a Program of the Center for Victims of Torture, which states that we can “change deeply held cultural narratives and open new space for our stories” with “Powerful narratives and effective story-based strategy [that] change cultural norms and [create] a space for new stories, ideas, and norms to flourish. [Center for Story-based Strategy] believes there is a moment they term a ‘psychic break’ that is the process or moment of realization whereby a deeply held dominant culture narrative comes into question, oftentimes stemming from a revelation that a system, event, or course of events is out of alignment with core values.”

Indeed, the Center for Story-based Strategy believes that “stories are embedded with power – the power to explain and justify the status quo as well as the power to make change imaginable and urgent. A narrative analysis of power encourages us to ask: Which stories define cultural norms? Where did these stories come from? Whose stories were ignored or erased to create these norms? And, most urgently, what new stories can we tell to help create the world we desire?”

Certainly, the world many in the US desire is one without the injustices we are seeing in our justice system. The United States’ incarceration rates are the highest in the world. According to the Sentencing Project, “There are 2.2 million people in the nation’s prisons and jails—a 500% increase over the last 40 years. Changes in law and policy, not changes in crime rates, explain most of this increase. The results are overcrowding in prisons and fiscal burdens on states, despite increasing evidence that large-scale incarceration is not an effective means of achieving public safety.” What of these 2.2 million in US prisons and jails—and many more who are in some way involved in the court and probation systems? Some are on death row, others are serving life without parole, still others will serve their sentences and be released, though rarely will they truly rejoin mainstream America. Certainly, their voices are “othered,” marginalized, and often silenced. They are othered and silenced by the justice system, the prison system, at times by fellow prisoners, by perceptions of the incarcerated in the larger culture, sometimes even unwittingly by the free public and the people who are studying and reporting on the plight of the incarcerated, the very people who mean to remediate the injustices within the system.

I hope that readers of Letters will question the “dominant cultural narrative” and demand change.

GM: Would you consider pursuing other anthologies like this, perhaps based around women’s confinement as well? What other new ideas and projects are you working on at the moment?

JT: Yes! Since July of 2019, I have been working at SCI Chester on a post-traumatic growth curriculum that was started by a professor at Widener University, Dr. Kit Healey. She is retiring, and I am taking it over and making it based more on reading and writing. Widener University students, incarcerated men, and I [started] an anthology project in January 2020. We are all so excited and curious to see what we will create.

I recently finished working on a project that gathered women’s voices. I was inspired while traveling to Europe for the first time. In Berlin, I stood gazing at the Käthe Kollwitz sculpture "Mother with Her Dead Son." This sculpture captured the horrors of war—and spoke of women’s experiences; Kollwitz, artist and pacifist, suffered great loss in a life that spanned the World Wars. I found it difficult to leave the space. I remembered the poem that I had read years before, Muriel Rukeyser’s “Kathe Kollwitz,” two lines of which had stuck with me, “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?/The world would split open.”

I returned to my women’s writing group in Chester, PA, and I watched women’s faces as I asked them to respond to Rukeyser’s words, and their reactions showed me that I might be onto something. To gather incarcerated women’s voices, we sent out a call to prisons, and we have submissions from England, Scotland, Australia, and many US states. We formed The World Split Open Story Collaborative with six women and requested assistance from scholar, poet and performance artist Andrea Zittlau of Rostock, Germany. The public arts project that resulted is in the spirit of street literature broadsides that were popular from the 16th to 19th centuries. Whether used to bring ballads, advertisements, or news to the public, they were undeniably important in history as a means for individuals to communicate with others in public places. We believe that bringing these pieces to the public is a modern nod to the broadside’s power to inform; in this case, we are making public the stories that women too often and for too long have kept private. Indeed, if we take the pulse of the United States at the moment, we see that many individuals, especially women, are coming forward to tell of abuses, particularly sexual abuses, they have experienced. Indeed, our project focuses on much the same theme: women coming forward to tell about their lives by responding to Muriel Rukeyser’s poem. We had no idea what would be happening in the public sphere when we began our public arts project, but we are excited to be part of this movement and hope to do our part to further its momentum