Interview

Paradoxes of Identity: AN INTERVIEW WITH Julie Enszer

BY Rachel Carly, Sarah Knapp, Myriah Stubee, & Alexis Zimmerman

MARCH 2017

Now more than ever, identities are being called into question, trivialized, and often dismissed. People are searching for validation and acceptance from society, peers, and even themselves. This affirmation often comes in the form of words.

Addressing these concerns in her poetry, Julie R. Enszer explores the “relationship between how we label ourselves and how others label us…[and explores] that dynamic tension.” Enszer provides voices for identities that are often marginalized by representing communities such as women, LGBTQ, and Jews. Tapping into social movements, mythology, and the complexity of identity, Enszer works to discover truth.

Addressing these concerns in her poetry, Julie R. Enszer explores the “relationship between how we label ourselves and how others label us…[and explores] that dynamic tension.” Enszer provides voices for identities that are often marginalized by representing communities such as women, LGBTQ, and Jews. Tapping into social movements, mythology, and the complexity of identity, Enszer works to discover truth.

Glassworks Magazine (GM): Many of your poems seem to be about identity, both in how we see ourselves and how others label us. Do you think that the majority of your poems work to question identity or to reaffirm and embrace it?

Julie R. Enszer (JRE): I am interested in the paradoxes of identity. For me, identity is something that has valence when people create meaning for it and imbue meaning into it, but simultaneously identity limits and constricts people. I am interested in that dynamic tension. What is the relationship between how we label ourselves and how others label us? How do we make identities visible and apprehensible to others, even, perhaps especially, when they are outside of our identity group? What made lesbian-feminist deeply and profoundly meaningful for a period of time during the 1970s and 1980s and how did queer eclipse its meaning in subsequent decades? These questions animate much of my scholarly work and my poetry.

While it is in the paradoxes and conflicts that I find identity most interesting, most productive to me intellectually and artistically, I also make no bones about being invested in identity work politically. I want to promote lesbianism, feminism, and Jewish values in my poetry, in my activism, and in my movements through the world. I am interested in work that brings people to affirm and embrace identity as well as productively questioning and challenging it.

GM: You identify as a lesbian Jewish poet, but much of your work features common human and universal experiences. What would you say to someone who might dismiss your poetry because they are not your target audience?

JRE: Audience is an important question to me because I believe a crucial part of identity work is the creation of audience for artists. During the 1970s and 1980s, feminists created their own audiences for work that was marginalized and dismissed in many cases by official tastemakers. The creation of a shared identity simultaneously produced a shared audience of lesbian and feminist artists. Though of course once the audience is created, once a community comes into being, it's limitations and constraints are exposed and many artists seem to then want to break out of that particular space, often while still honoring it and appreciating it. So I see the question of identity and audience working together dynamically from a structural level. Of course, we do not read, write, and experience poetry structurally or even often communally. It is an individual experience and often highly personal, even intimate.

GM: Who would you say is your target audience?

JRE: When I am writing, I am thinking only of myself as an audience; how can I uncover some basic truths about what I am thinking and experiencing? When I am rewriting, I have an imagined audience of one: an esteemed poetry professor of mine. I rewrite to satisfy him and his greatest aspirations for what poetry is, then the poetry starts to move out into the world. My greatest hope is that it finds an audience in the communities that I love and that hold me up, and also in communities outside of my own.

GM: There has been much debate recently about the definition and parameters of the word “feminist.” In modern speech, feminism can be thought to hold a negative connotation. Would you define or categorize your work as feminist?

JRE: There has always been lots of debate about the definition and parameters of the word “feminist!” Not only in recent years, but throughout the 1960s and 1970s and at other historical moments where women have been agitating for more rights. The more expansively we can understand the various contestations of feminism, the more we can embrace the current debates with zeal.

My greatest hope is that other people I admire will categorize my work as feminist, that it will be appraised as worthy of the label. I am a feminist, and so I see my work as feminist work, but the real determination of it comes, I think, from other people embracing it as feminist.

Given debates about feminist and feminism and their meanings, my own definition of feminism and feminist are processes that think deeply and critically about how to improve the material conditions of women’s lives. In the most basic ways, I am interested in all things that make women’s lives better. I recognize that while that may be a simple measure, in reality it is quite complex.

Julie R. Enszer (JRE): I am interested in the paradoxes of identity. For me, identity is something that has valence when people create meaning for it and imbue meaning into it, but simultaneously identity limits and constricts people. I am interested in that dynamic tension. What is the relationship between how we label ourselves and how others label us? How do we make identities visible and apprehensible to others, even, perhaps especially, when they are outside of our identity group? What made lesbian-feminist deeply and profoundly meaningful for a period of time during the 1970s and 1980s and how did queer eclipse its meaning in subsequent decades? These questions animate much of my scholarly work and my poetry.

While it is in the paradoxes and conflicts that I find identity most interesting, most productive to me intellectually and artistically, I also make no bones about being invested in identity work politically. I want to promote lesbianism, feminism, and Jewish values in my poetry, in my activism, and in my movements through the world. I am interested in work that brings people to affirm and embrace identity as well as productively questioning and challenging it.

GM: You identify as a lesbian Jewish poet, but much of your work features common human and universal experiences. What would you say to someone who might dismiss your poetry because they are not your target audience?

JRE: Audience is an important question to me because I believe a crucial part of identity work is the creation of audience for artists. During the 1970s and 1980s, feminists created their own audiences for work that was marginalized and dismissed in many cases by official tastemakers. The creation of a shared identity simultaneously produced a shared audience of lesbian and feminist artists. Though of course once the audience is created, once a community comes into being, it's limitations and constraints are exposed and many artists seem to then want to break out of that particular space, often while still honoring it and appreciating it. So I see the question of identity and audience working together dynamically from a structural level. Of course, we do not read, write, and experience poetry structurally or even often communally. It is an individual experience and often highly personal, even intimate.

GM: Who would you say is your target audience?

JRE: When I am writing, I am thinking only of myself as an audience; how can I uncover some basic truths about what I am thinking and experiencing? When I am rewriting, I have an imagined audience of one: an esteemed poetry professor of mine. I rewrite to satisfy him and his greatest aspirations for what poetry is, then the poetry starts to move out into the world. My greatest hope is that it finds an audience in the communities that I love and that hold me up, and also in communities outside of my own.

GM: There has been much debate recently about the definition and parameters of the word “feminist.” In modern speech, feminism can be thought to hold a negative connotation. Would you define or categorize your work as feminist?

JRE: There has always been lots of debate about the definition and parameters of the word “feminist!” Not only in recent years, but throughout the 1960s and 1970s and at other historical moments where women have been agitating for more rights. The more expansively we can understand the various contestations of feminism, the more we can embrace the current debates with zeal.

My greatest hope is that other people I admire will categorize my work as feminist, that it will be appraised as worthy of the label. I am a feminist, and so I see my work as feminist work, but the real determination of it comes, I think, from other people embracing it as feminist.

Given debates about feminist and feminism and their meanings, my own definition of feminism and feminist are processes that think deeply and critically about how to improve the material conditions of women’s lives. In the most basic ways, I am interested in all things that make women’s lives better. I recognize that while that may be a simple measure, in reality it is quite complex.

"While I revere community in many ways, I also know the painful and difficult parts of community; the ways that people are rejected, how lines are drawn that exclude"

GM: A sense of community among women seems to be a recurring theme in your earlier work and it was the main focus of your book, Sisterhood. It also seems to have had a significant influence on Lilith’s Demons. What is it about this theme that causes you to continually revisit it?

JRE: That’s a great question. The imaginary of women’s community was formative in my early years as a lesbian and feminist. What I mean by that is the creation of women’s communities was work that feminists and lesbians were all doing around me in early years of my life—first at the Women’s Crisis Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan, then at the Lesbian and Gay Community Center in metropolitan Detroit. Living in Michigan, the imagined community of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival was also an important part of my early years. While I revere community in many ways, I also know the painful and difficult parts of community; the ways that people are rejected, how lines are drawn that exclude. In poetry, I am always trying to work through these questions of community and understand what it means. I suppose, broadly, the theme is about reaching for, finding and failing at human connections.

GM: The theme of motherhood manifests in various earlier poems. How has this theme grown in complexity from your earlier poems?

JRE: This question is tough because of my own difficult relationship with my mother, who is now of blessed memory. In earlier poems, I was comfortable using my mother as a flat character—as a homophobic foil in some instances. Honestly, in many ways, I really like and preferred that way of engaging with her in my poems. However, in the past years, our relationship leading up to her death changed; she became more human to me, more vulnerable. She was not a flat character with whom I could only be angry. So the complexity of motherhood—and daughterhood—came into my work in ways that I am still thinking and working through.

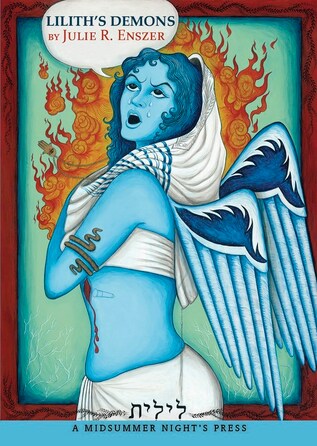

GM: How does motherhood influence your most recent book, Lilith’s Demons, specifically?

JRE: In Lilith’s Demons, I wanted to resist the idea of motherhood for Lilith and resist tropes of the demons as her children, though I know those exact ideas seeped into the book. It is difficult to talk about intergenerational relationships of women that are not organized by the societal scripts of mother/daughter relationships. One of the things I was trying to struggle with in Lilith’s Demons was how to do that.

GM: Naming the things you create has very maternal connotations. Names have also been linked with control in mythology and within our own world; to know something’s name is to have power over it. There are certain mythologies that state that you can only summon and control a demon if you know its name. In Lilith's Demons, the names seem to take on importance. How did the names contribute to the personality of each demon or angel?

JRE: Names for the demons was a way that I could imagine each of the women speaking in the poems being human. Here is another paradox in the writing: names suggest humanness even for demons. Of course, the idea of a demon is really about giving oneself over to the notion of being transgressive of human norms. Demons give voice and embodiment to the dark part of humanity, to things that are forbidden. So the very notion of a demon is linked to human. Names, then, offered a way to humanize the demons and find connections between ourselves and the demons. Demons embody what we do not want to be and put our lives into relief. One of the secrets of Lilith's Demons is that one hundred Demons are named in the book because Lilith spawns one hundred demons each night at dusk.

JRE: That’s a great question. The imaginary of women’s community was formative in my early years as a lesbian and feminist. What I mean by that is the creation of women’s communities was work that feminists and lesbians were all doing around me in early years of my life—first at the Women’s Crisis Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan, then at the Lesbian and Gay Community Center in metropolitan Detroit. Living in Michigan, the imagined community of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival was also an important part of my early years. While I revere community in many ways, I also know the painful and difficult parts of community; the ways that people are rejected, how lines are drawn that exclude. In poetry, I am always trying to work through these questions of community and understand what it means. I suppose, broadly, the theme is about reaching for, finding and failing at human connections.

GM: The theme of motherhood manifests in various earlier poems. How has this theme grown in complexity from your earlier poems?

JRE: This question is tough because of my own difficult relationship with my mother, who is now of blessed memory. In earlier poems, I was comfortable using my mother as a flat character—as a homophobic foil in some instances. Honestly, in many ways, I really like and preferred that way of engaging with her in my poems. However, in the past years, our relationship leading up to her death changed; she became more human to me, more vulnerable. She was not a flat character with whom I could only be angry. So the complexity of motherhood—and daughterhood—came into my work in ways that I am still thinking and working through.

GM: How does motherhood influence your most recent book, Lilith’s Demons, specifically?

JRE: In Lilith’s Demons, I wanted to resist the idea of motherhood for Lilith and resist tropes of the demons as her children, though I know those exact ideas seeped into the book. It is difficult to talk about intergenerational relationships of women that are not organized by the societal scripts of mother/daughter relationships. One of the things I was trying to struggle with in Lilith’s Demons was how to do that.

GM: Naming the things you create has very maternal connotations. Names have also been linked with control in mythology and within our own world; to know something’s name is to have power over it. There are certain mythologies that state that you can only summon and control a demon if you know its name. In Lilith's Demons, the names seem to take on importance. How did the names contribute to the personality of each demon or angel?

JRE: Names for the demons was a way that I could imagine each of the women speaking in the poems being human. Here is another paradox in the writing: names suggest humanness even for demons. Of course, the idea of a demon is really about giving oneself over to the notion of being transgressive of human norms. Demons give voice and embodiment to the dark part of humanity, to things that are forbidden. So the very notion of a demon is linked to human. Names, then, offered a way to humanize the demons and find connections between ourselves and the demons. Demons embody what we do not want to be and put our lives into relief. One of the secrets of Lilith's Demons is that one hundred Demons are named in the book because Lilith spawns one hundred demons each night at dusk.

"Demons give voice and embodiment to the dark part of humanity, to things that are forbidden. So the very notion of a demon is linked to human."

|

GM: In all the religious myths surrounding Lilith, she is portrayed as a demon and an outcast, something to be feared and reviled. Many modern day people (even active religious people) do not know the story of Lilith, or, if they know of her, they don’t know her full story and why she is hated within religious teaching. What new perspective are you adding to her character?

JRE: Yes, Lilith is the demon and outcast, but Jewish feminists have reclaimed her as a powerful autonomous woman. I have been reading the feminist magazine Lilith for many years and know Judith Plaskow’s midrash on Lilith from the 1970s. So in many ways, one of the greatest challenges I had in writing Lilith's Demons was to not fall into writing and thinking about Lilith in ways that feminists had already. I wanted to write something new. |

GM: What drew you to the character of Lilith?

JRE: The truth is, I do not feel that I chose Lilith as a subject for my work; she chose me. I started writing the poems of the collection as odd persona poems, originally written during a terrible bout of summer insomnia. The poems evolved and it became clear that they had a link, but for a number of weeks, I did not know what the link was. I was just writing these short persona poems that seemed somehow twisted, even unruly. I kept at it though, each night imagining a new poem as I was awake in the early hours before sunrise. Then one day it became clear to me that the poems were lined through Lilith. Then, the idea of them being persona poems in the voices of Lilith's Demons emerged and I was off on the collection. It came together quickly and decisively.

JRE: The truth is, I do not feel that I chose Lilith as a subject for my work; she chose me. I started writing the poems of the collection as odd persona poems, originally written during a terrible bout of summer insomnia. The poems evolved and it became clear that they had a link, but for a number of weeks, I did not know what the link was. I was just writing these short persona poems that seemed somehow twisted, even unruly. I kept at it though, each night imagining a new poem as I was awake in the early hours before sunrise. Then one day it became clear to me that the poems were lined through Lilith. Then, the idea of them being persona poems in the voices of Lilith's Demons emerged and I was off on the collection. It came together quickly and decisively.

GM: You write about a lot of explicit subject matter, as well as some seemingly personal emotions. Poetry, more than many other genres, really requires authors to share themselves on the page. Is this something you have struggled with?

JRE: The struggle for me is to sort out what the emotions are—what I really think and feel about the subject matter. Generally, in my early drafts, I do not know what I think or feel about the subject; I am writing to discover my own internal landscape. I always honor that process. The best poems for me are where the poet discovers something for herself and the reader discovers it simultaneously along with the poet.

Then the question is after the discovery: Do I want to share this with other people? Can it serve other people to know this discovery, this explication of the internal life? And, to your question, what other people are implicated in my discoveries?

One of the most delightful things I heard a writer say recently was that her father said of her memoir, "I have different memories about what you write about; but your writing is yours—your stories, your memories. Mine can be different." That is how I think of my writing. I want to tell my stories. I want to hold others, particularly beloved others, close and I want others to see them generously and lovingly in the poems, though I know sometimes I fail at that. Other people have different memories and stories. I am telling mine and trying to create space for others to tell theirs.

JRE: The struggle for me is to sort out what the emotions are—what I really think and feel about the subject matter. Generally, in my early drafts, I do not know what I think or feel about the subject; I am writing to discover my own internal landscape. I always honor that process. The best poems for me are where the poet discovers something for herself and the reader discovers it simultaneously along with the poet.

Then the question is after the discovery: Do I want to share this with other people? Can it serve other people to know this discovery, this explication of the internal life? And, to your question, what other people are implicated in my discoveries?

One of the most delightful things I heard a writer say recently was that her father said of her memoir, "I have different memories about what you write about; but your writing is yours—your stories, your memories. Mine can be different." That is how I think of my writing. I want to tell my stories. I want to hold others, particularly beloved others, close and I want others to see them generously and lovingly in the poems, though I know sometimes I fail at that. Other people have different memories and stories. I am telling mine and trying to create space for others to tell theirs.

"The best poems for me are where the poet discovers something for herself and the reader discovers it simultaneously along with the poet."

|

GM: You seem concerned with representing the people you care about, but there also seems to be many different ways in which you represent yourself through your work, connecting to Jewish heritage, strong feminist themes, and also LGBTQ. How do these different aspects of your identity connect with your work? Is there any one narrative voice that you feel is most authentically “you”?

JRE: For me, one of the lovely things about having now a body of work – Lilith’s Demons is my third collection, my fourth collection, Avowed, is being published now by Sibling Rivalry Press—is that I can see the multiplicity of the voice and also recognize it is mine, though changing across the years and projects. Certainly, all of us have a quest to find an authentic voice, but that quest is one that is never resolved; we continue over a lifetime to write what we feel to be true and honest. I have just moved to Florida after a nine month sojourn in Michigan. I grew up in Michigan and the landscape there is deeply familiar. I know what it smells like there each month of the year. I know the landscape, the angles of the sun, where to find the moon and the stars. It was incredible to be back and realize how much growing up there shaped my sense of the natural world. In Florida, I recognize little. The plants are all new. The insects are all different. The sun and moon seem to behave in different ways. I find myself struggling to write in a way that locates myself in this strange new geography. I am grateful for that struggle and re-engagement in examining: who am I? How do I speak and write? |

GM: Your poems continue to grow and evolve the more you write, which is any writer’s goal. Will there be more character studies as we’ve seen in Lilith’s Demons and do you see yourself writing more personal narrative poetry? Considering your ongoing themes of identity, what are your goals in continuing to challenge your readers?

JRE: Ah! As I was wrapping up the poems of Lilith's Demons, a dear writing buddy suggested to me that I should do poems about the creatures of Lilith's garden. That intrigues me. The unicorns, of course, the butterflies, the bats. I can imagine many possibilities here. I have that idea percolating in the back of my mind. Right now, I am working to promote the new collection, Avowed, which are personal poems that explore the contours of a long term, lesbian relationship. I just edited The Complete Works of Pat Parker and working with her poems has me engaged in writing poems that think about race and racism. I find myself always with new poems on my mind and finding their way onto the page.

In general, I want people to read what they love, what delights them and what challenges them in productive and meaningful ways. I also want people to recognize that what might not speak to them one moment might speak to a future self. I always encourage readers and writers to not be dismissive in sweeping ways; our reading lives are long but our daily attention is limited. This is the paradox that we all live within most productively when we embrace openness and eschew dismissiveness.

JRE: Ah! As I was wrapping up the poems of Lilith's Demons, a dear writing buddy suggested to me that I should do poems about the creatures of Lilith's garden. That intrigues me. The unicorns, of course, the butterflies, the bats. I can imagine many possibilities here. I have that idea percolating in the back of my mind. Right now, I am working to promote the new collection, Avowed, which are personal poems that explore the contours of a long term, lesbian relationship. I just edited The Complete Works of Pat Parker and working with her poems has me engaged in writing poems that think about race and racism. I find myself always with new poems on my mind and finding their way onto the page.

In general, I want people to read what they love, what delights them and what challenges them in productive and meaningful ways. I also want people to recognize that what might not speak to them one moment might speak to a future self. I always encourage readers and writers to not be dismissive in sweeping ways; our reading lives are long but our daily attention is limited. This is the paradox that we all live within most productively when we embrace openness and eschew dismissiveness.

Find out more about Julie Enszer on her website: https://julierenszer.com/