Interview

Too White, But Not Colorblind: How Kelly Norris Utilizes Privilege for Racial Justice

BY aNN cAPUTO, jOE gRAMIGNA, & iSHA sTRASSER

October 2019

America continues to struggle with racial tensions. White power groups are finding community on social media. Black girls are hyper-sexualized by the media and their peers. Immigrants are being turned away from our country in waves based on the demonization of their cultures and their skin. And yet, substantive dialogues about the tensions running under our nation are rare, leading to major rifts and clashes.

Growing up in a privileged Connecticut town, Kelly Norris felt imprisoned and misrepresented by her “whiteness.” Eager to shed her white identity, she searched for a new cultural “home.” Thus began Norris’ odyssey toward belonging.

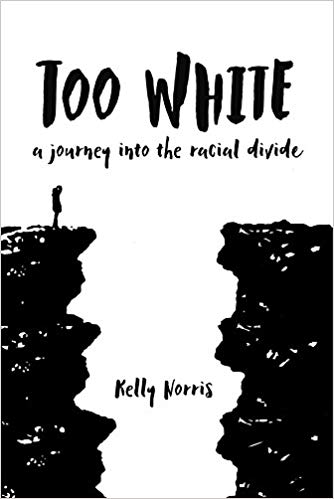

Norris’ memoir Too White dives into the challenges of racial identity and race politics in America. This often surprising, occasionally disturbing coming-of-age story explores how a young white suburban girl pushed the boundaries of identity and belonging within racialized cultures to become an educator, author, and activist. Her disarming honesty offers fresh perspectives on the need for white culture to engage with the difficult and dynamic challenge of dismantling racism in America.

In this exclusive interview with Glassworks, Kelly Norris shares her thoughts on white privilege while advising how to unpack our assumptions about race. Her thoughtful, self-confronting reflection points towards ways to disrupt systemic racism.

Growing up in a privileged Connecticut town, Kelly Norris felt imprisoned and misrepresented by her “whiteness.” Eager to shed her white identity, she searched for a new cultural “home.” Thus began Norris’ odyssey toward belonging.

Norris’ memoir Too White dives into the challenges of racial identity and race politics in America. This often surprising, occasionally disturbing coming-of-age story explores how a young white suburban girl pushed the boundaries of identity and belonging within racialized cultures to become an educator, author, and activist. Her disarming honesty offers fresh perspectives on the need for white culture to engage with the difficult and dynamic challenge of dismantling racism in America.

In this exclusive interview with Glassworks, Kelly Norris shares her thoughts on white privilege while advising how to unpack our assumptions about race. Her thoughtful, self-confronting reflection points towards ways to disrupt systemic racism.

Glassworks Magazine (GM): You recently published your memoir, Too White, your account of confronting racial issues in America. As you know, “white” is a racial category that carries a charged, racist history, at times prohibiting entry to groups of immigrants from places like Italy, Ireland, or Eastern Europe; groups that are now fully subsumed into the category of “white.” How do you navigate these complex histories in your writing, activist work, and in your family.

Kelly Norris (KN): I don't know that I really break 'white' down like that in the memoir, although I do teach some of that history in my classes. For me, the definition of white that I was interested in was the one of privilege, which most of us with European ancestry have by now. Though assimilation was harder for some--I mention this in the anecdote I tell about the Italian kids in my school, who were definitely more working-class in our community--I wanted to address the privileged group I belonged to, where there was no question about the unearned advantages I was given, like the assumption of innocence, and the accumulated wealth of my family. I do have some Irish blood, and it's interesting to learn about the struggles they had, but the Irish were quickly absorbed into the 'white' family and given the same privileges, so I don't buy the argument that I am somehow oppressed if I'm Irish. America had this turning point where Europeans were invited into the 'white' contract, in order to keep the peace and keep blacks and other people of color in a subordinate class, and many Europeans sold out their individual identities and cultures in order to just become 'white.' I guess I do address this a little in the book, because for a while I kind of felt a loss, a disconnection from my heritage, and I was envious of people who seemed more in touch with their ethnic background. But I guess that's the price of privilege.

GM: In your book, you included instances where you were forced to confront your own privilege. A moment that sticks out to us is when you told your dance teacher you had studied in Ghana and she responded by telling you how lucky you were. Do you think white privilege plays a role in your writing? How do you balance your role as an ally with the voices of those you’re trying to support?

KN: Yes. I worried all the time during writing, and still do, that my privilege shows in this book in ways I am unaware of. And I'm sure it does. But that doesn't stop me. Just because I'm not completely aware or woke or whatever, that doesn't mean I can't share the insight I do have. It's a constant process. There's no degree from the school of race-consciousness where suddenly you have no more racism and can see everything clearly. But I have forgiven myself for the flaws that a racist system has bred in me, and have committed myself to keep learning. And that's all I can do. I really assert my voice in white spaces--sort of like when I go back into the more hostile world--I share what I know and challenge folks who may not be as far along as me in understanding race and racism, and I often find myself drawing on my mentors and leaders in the activist community. Their voices help me find my own.

Because I know my writing was published at least in part because of my privilege--my education and access to certain social circles--I plan to donate some of the profits from this book to activist groups in my area, who’ve been doing this work and sending these messages all along. I also work as a teacher, where one of my main goals is to empower marginalized kids to tell their stories, and find and create spaces to share their voices.

GM: What was your experience with the publishing industry when getting this book published? Do you consider the publishing world to be “too white?”

KN: Ha. That's a good question. I had some really bad experiences sharing this book. The topic, as soon as I would raise it, would usually trigger some white person's own racial baggage, and before I knew it, we were entrenched in a story of theirs about some racially charged incident that they needed to work out and my book was completely forgotten. This happened all the time, in conversations, workshops, on social media, and with potential publishers. What that says to me is that we really need to talk about this stuff. It seems every white person has a secret story involving race that needs sharing--and I've recently begun asking my students to share theirs in writing, which is often safer than out loud. But in general, no, I don't think the industry is too white. I think there's lots of room these days for POC to tell their stories and to do very well. But at the same time, I think a book like mine will never be mainstream because it disrupts the sort of contract of silence white people have around race. It's a little too confrontational, but hopefully one day it will just seem normal, once we all 'get it.'

Kelly Norris (KN): I don't know that I really break 'white' down like that in the memoir, although I do teach some of that history in my classes. For me, the definition of white that I was interested in was the one of privilege, which most of us with European ancestry have by now. Though assimilation was harder for some--I mention this in the anecdote I tell about the Italian kids in my school, who were definitely more working-class in our community--I wanted to address the privileged group I belonged to, where there was no question about the unearned advantages I was given, like the assumption of innocence, and the accumulated wealth of my family. I do have some Irish blood, and it's interesting to learn about the struggles they had, but the Irish were quickly absorbed into the 'white' family and given the same privileges, so I don't buy the argument that I am somehow oppressed if I'm Irish. America had this turning point where Europeans were invited into the 'white' contract, in order to keep the peace and keep blacks and other people of color in a subordinate class, and many Europeans sold out their individual identities and cultures in order to just become 'white.' I guess I do address this a little in the book, because for a while I kind of felt a loss, a disconnection from my heritage, and I was envious of people who seemed more in touch with their ethnic background. But I guess that's the price of privilege.

GM: In your book, you included instances where you were forced to confront your own privilege. A moment that sticks out to us is when you told your dance teacher you had studied in Ghana and she responded by telling you how lucky you were. Do you think white privilege plays a role in your writing? How do you balance your role as an ally with the voices of those you’re trying to support?

KN: Yes. I worried all the time during writing, and still do, that my privilege shows in this book in ways I am unaware of. And I'm sure it does. But that doesn't stop me. Just because I'm not completely aware or woke or whatever, that doesn't mean I can't share the insight I do have. It's a constant process. There's no degree from the school of race-consciousness where suddenly you have no more racism and can see everything clearly. But I have forgiven myself for the flaws that a racist system has bred in me, and have committed myself to keep learning. And that's all I can do. I really assert my voice in white spaces--sort of like when I go back into the more hostile world--I share what I know and challenge folks who may not be as far along as me in understanding race and racism, and I often find myself drawing on my mentors and leaders in the activist community. Their voices help me find my own.

Because I know my writing was published at least in part because of my privilege--my education and access to certain social circles--I plan to donate some of the profits from this book to activist groups in my area, who’ve been doing this work and sending these messages all along. I also work as a teacher, where one of my main goals is to empower marginalized kids to tell their stories, and find and create spaces to share their voices.

GM: What was your experience with the publishing industry when getting this book published? Do you consider the publishing world to be “too white?”

KN: Ha. That's a good question. I had some really bad experiences sharing this book. The topic, as soon as I would raise it, would usually trigger some white person's own racial baggage, and before I knew it, we were entrenched in a story of theirs about some racially charged incident that they needed to work out and my book was completely forgotten. This happened all the time, in conversations, workshops, on social media, and with potential publishers. What that says to me is that we really need to talk about this stuff. It seems every white person has a secret story involving race that needs sharing--and I've recently begun asking my students to share theirs in writing, which is often safer than out loud. But in general, no, I don't think the industry is too white. I think there's lots of room these days for POC to tell their stories and to do very well. But at the same time, I think a book like mine will never be mainstream because it disrupts the sort of contract of silence white people have around race. It's a little too confrontational, but hopefully one day it will just seem normal, once we all 'get it.'

"So going over there, I saw that the Black Americans were just as out of place as me, and that kind of dispelled some myth in my head, but it would still be a long time before I realized all my stereotypes and assumptions about commonalities between Black people."

GM: Early in your memoir, you describe the decision to study at the University of Ghana; how did that experience contextualize your understanding of American Black culture? How do you use your writing to create opportunities to reimagine racial or ethnic categories for Americans?

KN: I think I went over there, to Ghana, seeing all Black people as one, you know, like there was some genetic code they all shared, which is a really common manifestation of racism. White people are viewed as individuals whereas people of color are often viewed as part of a group, which comes attached to lots of stereotypes, etc. So going over there, I saw that the Black Americans were just as out of place as me, and that kind of dispelled some myth in my head, but it would still be a long time before I realized all my stereotypes and assumptions about commonalities between Black people. That said, I also saw this vibrancy and innocence in Ghanaian culture, this sort of joy untainted by cynicism, and so I was able to counter the really negative narrative of Black people I had grown up with. So when I came home, I was able to see Black people as more human, more good, and maybe even went a little overboard with that, like the pendulum swung too far the other way and I was in love with every

Black person I saw. Kind of ridiculous, but that was my process. So in my writing now, I really just want to humanize people. There's something dehumanizing about assuming a whole group of people are one way, whether it's positive or negative.

GM: How does writing about race from the perspective of a white woman disrupt, rework, or contribute to more social awareness?

KN: Well, that's interesting because I have doubted myself at times, and been doubted by others, because of my position as a white woman in writing about this subject. I don't want to take up more space, as a white person. Our stories are already at the center of the narrative most of the time, and it's important to create space for people of color to tell their stories. But, Robin DiAngelo, who recently published the great book, White Fragility, said that in order to decentralize whiteness we need to centralize it first, really look at it, study it, especially those of us who are white, and learn how it works so we can start resisting the ways in which our white identity oppresses others. So I think white people bear the responsibility to help each other out with this. And for some whites, they can't really hear criticism from people of color, they're just not there yet, so to hear about whiteness and privilege from someone like me, may be the only way they'll listen.

GM: What are some ways that white people can utilize their privilege to act as allies? What writers would you suggest to diversify their reading?

KN: There is always a way for white folks to utilize their privilege for racial justice. Whatever your sphere of influence is, however big or small. There's this one example of the white woman in line at the grocery store and she pays with a check and the cashier accepts it. Then, when the woman of color behind her also tries to pay with a check, she gets asked for an ID. So the white woman speaks up and demands to know why this is happening. That's the kind of small stuff we can do. That whole Starbucks incident with the two guys getting thrown out, and arrested, got so much attention, in part, because a white person filmed it and put it on social media. Use your freedom as a white person to occupy space and to be presumed innocent to expose when POC are denied these privileges. That's one way. But maybe you have more structural advantage than that. If you are the head of a company or work in education or at a bank, can you consider the ways in which your organization includes or doesn't include POC? Can you consider how racism may be perpetuated by your work? And if you're not sure, you can hire a diversity consultant or someone else to look into it for you.

Writers I loved that helped me along were Tim Wise, Beverly Tatum, James Baldwin, and Barack Obama. More recently I read Debbie Irving, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and Robin DiAngelo.

Black person I saw. Kind of ridiculous, but that was my process. So in my writing now, I really just want to humanize people. There's something dehumanizing about assuming a whole group of people are one way, whether it's positive or negative.

GM: How does writing about race from the perspective of a white woman disrupt, rework, or contribute to more social awareness?

KN: Well, that's interesting because I have doubted myself at times, and been doubted by others, because of my position as a white woman in writing about this subject. I don't want to take up more space, as a white person. Our stories are already at the center of the narrative most of the time, and it's important to create space for people of color to tell their stories. But, Robin DiAngelo, who recently published the great book, White Fragility, said that in order to decentralize whiteness we need to centralize it first, really look at it, study it, especially those of us who are white, and learn how it works so we can start resisting the ways in which our white identity oppresses others. So I think white people bear the responsibility to help each other out with this. And for some whites, they can't really hear criticism from people of color, they're just not there yet, so to hear about whiteness and privilege from someone like me, may be the only way they'll listen.

GM: What are some ways that white people can utilize their privilege to act as allies? What writers would you suggest to diversify their reading?

KN: There is always a way for white folks to utilize their privilege for racial justice. Whatever your sphere of influence is, however big or small. There's this one example of the white woman in line at the grocery store and she pays with a check and the cashier accepts it. Then, when the woman of color behind her also tries to pay with a check, she gets asked for an ID. So the white woman speaks up and demands to know why this is happening. That's the kind of small stuff we can do. That whole Starbucks incident with the two guys getting thrown out, and arrested, got so much attention, in part, because a white person filmed it and put it on social media. Use your freedom as a white person to occupy space and to be presumed innocent to expose when POC are denied these privileges. That's one way. But maybe you have more structural advantage than that. If you are the head of a company or work in education or at a bank, can you consider the ways in which your organization includes or doesn't include POC? Can you consider how racism may be perpetuated by your work? And if you're not sure, you can hire a diversity consultant or someone else to look into it for you.

Writers I loved that helped me along were Tim Wise, Beverly Tatum, James Baldwin, and Barack Obama. More recently I read Debbie Irving, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and Robin DiAngelo.

|

GM: You mention your early interactions with race as a child in K-Mart “that made [you] cower and steal behind your mother’s legs.” On your trip to the Stamford Town Center with your friends, you “had the panicked thought of rushing inside for help or finding a payphone and calling home” when you had a confrontation with a group of Black girls. Both of these interactions are steeped in fear. How can we approach issues of race with children?

|

"There is always a way for white folks to utilize their privilege for racial justice. Whatever your sphere of influence is, however big or small." |

KN: Yes, fear is really at the heart of a lot of our racial separation. We are taught to be afraid of POC, afraid to do or say something 'racist,' and so we are afraid to even talk about the subject. For me, in my classroom I try to create a safe space to have conversations. It's usually much easier for kids to write first, then share with just one person before having a large conversation. But I think we have to go there. And the administration of a school can do a lot to create a culture where talking about race and other systems of oppression becomes the norm. But as for the bodily, person-to-person fear whites are socialized to have around black people, I think the only thing that makes that go away is meaningful social contact, real relationships.

GM: We meet your daughter on p. 177. You describe her as having “thick black hair and dark eyes that seemed to recognize [you] as [you] stared at each other.” How do you educate her on her “white” heritage? Can you share any specific narrative examples of how you approach this topic with her? Are there any aspects of the white culture you wish for Yacine to absorb?

KN: Do I talk to her about white privilege and racism? Yes. When she was little, I would help her understand racist stereotypes in Disney movies and talk to her about racism and slavery and things like that, but I think she really started to get it around middle school, when her friends and teachers were talking about those things, too, and she was feeling some of it. One day she said, about middle school, "The black kids have all the power in the hallways, but the white kids have all the power in the classroom." So we talked about why that is.

Now, as a senior in high school, she educates me. She is incredibly engaged with and perceptive about issues of race and whiteness and privilege, including her own, but very in touch with her blackness as well. As a dark-skinned girl, she never identified as anything but Black, because that's how she's perceived. In spite of the really awful racist things some white people are doing right now, that make it hard for her to want to identify as being white, I hope she learns to appreciate the values her white family gave her. My parents are both naturalists, and there’s this really big rift between whites and blacks in America when it comes to experiencing nature. It’s about access really, but the stereotype is that only whites go camping and hiking and stuff like that, so that’s one thing I hope she can absorb, the importance of having a relationship with the outdoors.

GM: Sometimes we hear people say they don’t see color and/or race. Do you think people can ever look past race, and if so, is it a good thing? Could we leave out important cultural/racial contexts and background that informs a people’s lives/experiences?

KN: No. I don’t think we ever can or should look past race. It’s so entrenched in our history that it impacts a great deal about our experience on this planet. You can’t really celebrate difference while you are still clearly living in a racial hierarchy. And you certainly can’t solve things by overlooking it. Colorblindness is an attempt to ignore the problem of racism and circumvent the hard work of facing your privilege; in my experience, it is an approach mostly espoused by white people. There’s this story of a black father trying to speak to his son’s teacher about the racism he’s noticed in her class, and she says, “I don’t see color.” So the father responds, “Then why are all the pictures on your walls of white people?”

GM: We meet your daughter on p. 177. You describe her as having “thick black hair and dark eyes that seemed to recognize [you] as [you] stared at each other.” How do you educate her on her “white” heritage? Can you share any specific narrative examples of how you approach this topic with her? Are there any aspects of the white culture you wish for Yacine to absorb?

KN: Do I talk to her about white privilege and racism? Yes. When she was little, I would help her understand racist stereotypes in Disney movies and talk to her about racism and slavery and things like that, but I think she really started to get it around middle school, when her friends and teachers were talking about those things, too, and she was feeling some of it. One day she said, about middle school, "The black kids have all the power in the hallways, but the white kids have all the power in the classroom." So we talked about why that is.

Now, as a senior in high school, she educates me. She is incredibly engaged with and perceptive about issues of race and whiteness and privilege, including her own, but very in touch with her blackness as well. As a dark-skinned girl, she never identified as anything but Black, because that's how she's perceived. In spite of the really awful racist things some white people are doing right now, that make it hard for her to want to identify as being white, I hope she learns to appreciate the values her white family gave her. My parents are both naturalists, and there’s this really big rift between whites and blacks in America when it comes to experiencing nature. It’s about access really, but the stereotype is that only whites go camping and hiking and stuff like that, so that’s one thing I hope she can absorb, the importance of having a relationship with the outdoors.

GM: Sometimes we hear people say they don’t see color and/or race. Do you think people can ever look past race, and if so, is it a good thing? Could we leave out important cultural/racial contexts and background that informs a people’s lives/experiences?

KN: No. I don’t think we ever can or should look past race. It’s so entrenched in our history that it impacts a great deal about our experience on this planet. You can’t really celebrate difference while you are still clearly living in a racial hierarchy. And you certainly can’t solve things by overlooking it. Colorblindness is an attempt to ignore the problem of racism and circumvent the hard work of facing your privilege; in my experience, it is an approach mostly espoused by white people. There’s this story of a black father trying to speak to his son’s teacher about the racism he’s noticed in her class, and she says, “I don’t see color.” So the father responds, “Then why are all the pictures on your walls of white people?”

"American culture has a strange obsession with blackness, while at the same time punishing and criminalizing it." |

GM: On the other side of the spectrum, many people fetishize blackness, both sexually and through reproduction. In Part Four, you describe your desire to have a Black baby because you thought “An all white baby...would be ghostly, deprived of some vital life force that [you] still attributed to black skin…[you] wanted a black baby to solidify [your] image, to show the world forever that [you were] not too white” (176). At any point, did you feel like you were a part of fetishizing the Black community/experience?

|

KN: I absolutely fetishized black skin and Black cultures, and for a while I thought that was something weird about me, but really it’s not. American culture has a strange obsession with blackness, while at the same time punishing and criminalizing it. James Baldwin puts it best, I think, when he writes about how whites repressed their own urges, like sexuality and expressions of joy like music and dancing, but then they projected those repressed desires onto Black people and simultaneously condemned and envied them for being able to act on those urges. This abusive dynamic is evident in how suburban kids will use Black lingo or dress in Black styles, listen to Black music, all the while being quite unaware of the community that those things come from, and having some pretty racist political opinions (that was me at one time as well). So, I think we need to own up to our appreciation and adoption of Black forms of expression, and use them as a jumping off point to understand each other, really examine race relations in this country, including our own place in the scheme of things, even if that means recognizing the privilege we are exerting in taking culture markers that are not ours.

Another thing I’ll say is that, as a white person, I did at one point see Black people as having the key to a more liberated, sensual way of living. After Ghana, I coveted the culture I saw there, the vibrancy in speech, dress, music, socializing, etc., and thought I had to “act black,” and be around exclusively Black people to have access to it. But as I aged, I realized we all have the ability to cultivate a more joyful, sensual, and vibrant experience of life. I’d just been taught to shy away from certain behaviors (I still blame the Puritans). But it’s a choice, for anybody, of how you want to approach life and live in your body. You don’t have to try to be somebody else.

GM: When you were young did you ever imagine yourself writing about racial issues? In what ways have you seen the American conception of race change the most? At what point in your life did you feel comfortable enough to start speaking and writing on issues of race?

KN: I absolutely did not imagine myself writing about race. I was pretty racist as a kid. And let me be clear, we were a 'normal' suburban white family, on the very liberal side of things, not neo-nazis or anything like that. And still, I laughed at racist jokes, felt superior to people of color, and harbored lots of negative stereotypes about why poor people (who in southern Connecticut were mostly people of color) were poor; I thought it was their own fault. That all started to shift in high school, then I made some diverse friends in college, lived in Ghana, but it was really once I was a teacher, standing in front of a roomful of kids of color, and really loving them, but also noticing I harbored some really negative thinking about them, that the cognitive dissonance really set in. There's something about teaching, a blessing really, that makes you grow. You can't be responsible for helping children blossom when you are a tangled mess. So It wasn't until I was in my thirties and I'd been working on myself that I started to speak and write about race.

I've seen the American conception of race shift dramatically because of the internet/social media. My daughter and her friends see videos or posts about white privilege and police brutality and microaggressions. They have the language for issues of race and identity that I wasn't exposed to until recently. For example, I love those little videos MTV does about issues related to race. I sometimes use them in my classroom, and they are fairly well-known. So that gives me hope. When I grew up in Connecticut, I would have never been exposed to something like Ta-Nehisi Coates' short speech about why white people shouldn't use the N-word. It's brilliant. But I would never have heard his, or almost any other person of color's perspective in segregated Connecticut. With the internet and all the communicating that is constantly happening, I can educate myself if I want to, by tuning in to different perspectives than mine. That's pretty cool. So I think kids today are more savvy. Hopefully they'll use what they know.

Another thing I’ll say is that, as a white person, I did at one point see Black people as having the key to a more liberated, sensual way of living. After Ghana, I coveted the culture I saw there, the vibrancy in speech, dress, music, socializing, etc., and thought I had to “act black,” and be around exclusively Black people to have access to it. But as I aged, I realized we all have the ability to cultivate a more joyful, sensual, and vibrant experience of life. I’d just been taught to shy away from certain behaviors (I still blame the Puritans). But it’s a choice, for anybody, of how you want to approach life and live in your body. You don’t have to try to be somebody else.

GM: When you were young did you ever imagine yourself writing about racial issues? In what ways have you seen the American conception of race change the most? At what point in your life did you feel comfortable enough to start speaking and writing on issues of race?

KN: I absolutely did not imagine myself writing about race. I was pretty racist as a kid. And let me be clear, we were a 'normal' suburban white family, on the very liberal side of things, not neo-nazis or anything like that. And still, I laughed at racist jokes, felt superior to people of color, and harbored lots of negative stereotypes about why poor people (who in southern Connecticut were mostly people of color) were poor; I thought it was their own fault. That all started to shift in high school, then I made some diverse friends in college, lived in Ghana, but it was really once I was a teacher, standing in front of a roomful of kids of color, and really loving them, but also noticing I harbored some really negative thinking about them, that the cognitive dissonance really set in. There's something about teaching, a blessing really, that makes you grow. You can't be responsible for helping children blossom when you are a tangled mess. So It wasn't until I was in my thirties and I'd been working on myself that I started to speak and write about race.

I've seen the American conception of race shift dramatically because of the internet/social media. My daughter and her friends see videos or posts about white privilege and police brutality and microaggressions. They have the language for issues of race and identity that I wasn't exposed to until recently. For example, I love those little videos MTV does about issues related to race. I sometimes use them in my classroom, and they are fairly well-known. So that gives me hope. When I grew up in Connecticut, I would have never been exposed to something like Ta-Nehisi Coates' short speech about why white people shouldn't use the N-word. It's brilliant. But I would never have heard his, or almost any other person of color's perspective in segregated Connecticut. With the internet and all the communicating that is constantly happening, I can educate myself if I want to, by tuning in to different perspectives than mine. That's pretty cool. So I think kids today are more savvy. Hopefully they'll use what they know.