Interview

Challenging Conventions: An interview with meghan lamb

BY garret castle, john castle, ariana tucker

MARCH 2022

Every once in a while, you come across an author whose work makes you stop in your tracks and question everything you know about writing. These writers challenge your perception of what a book can be and open your mind to styles of storytelling you didn’t even know existed. Meghan Lamb is one of these authors. Not only does her work span multiple genres, but it also challenges the conventions of those very genres in the process. You can observe this in her latest novel, Failure to Thrive, where she manages to weave together elements of things that are real and imagined. In this interview with Glassworks, Lamb gives insight into her process while writing Failure to Thrive and shares her perspective on the relationship between language and plot.

Glassworks Magazine (GM): The title of your latest novel, Failure to Thrive, comes from a medical phenomenon where babies develop slowly and become malnourished. The coal mining town seems to be dealing with forms of self-destruction and slow decay. Can you talk a little bit about this theme and what inspired you to explore it?

Meghan Lamb (ML): Even before I had any awareness of the PA Coal Region and the area’s specific overlapping issues (between the environmental “sickness” of the space and the sickness of its residents), I had a deep personal background with issues of illness, disability, and mental and emotional decay with environmental roots. Throughout my teen years, my family home was a foster home, so I actually lived with a number of kids who were diagnosed with “failure to thrive” in response to various mental health issues, PTSD, emotional and physical comorbidities. My mother was a special education teacher, and I also spent much of my teen years and 20s working with kids and adults with physical and intellectual disabilities. I was always struck by the ways people tended to “act out”—especially in self-harming ways—when they were experiencing some kind of internal struggle they couldn’t communicate, some kind of trauma they felt trapped—alone—inside. And over the many years I worked with kids and adults with physical and intellectual disabilities, I saw a lot of self-harm—biting of hands, scratching of faces, bashing of heads—that seemed to extend from the same situation: “I need something. I don’t have the language to express what I need. And you aren’t listening to me.”

I landed on this particular diagnostic terminology for the title of my novel because it has always seemed so oddly judge-y to me, such an apt embodiment of that failure to communicate. And this seems like the kind of judgment that people cast upon others when they aren’t listening when they aren’t considering the complexities of peoples’ needs. It’s the kind of judgment cast both upon people (who are struggling with issues of illness and disability) and places like the Coal Region (which are themselves—in many ways—suffering from a kind of terminal sickness). I guess one of my primary hopes for this novel is that it embodies the emotional and sensory experiences of this sickness, that it helps readers investigate these kinds of judgments (and—perhaps, in a more abstract sense—to inhabit those judgments along with these characters).

Meghan Lamb (ML): Even before I had any awareness of the PA Coal Region and the area’s specific overlapping issues (between the environmental “sickness” of the space and the sickness of its residents), I had a deep personal background with issues of illness, disability, and mental and emotional decay with environmental roots. Throughout my teen years, my family home was a foster home, so I actually lived with a number of kids who were diagnosed with “failure to thrive” in response to various mental health issues, PTSD, emotional and physical comorbidities. My mother was a special education teacher, and I also spent much of my teen years and 20s working with kids and adults with physical and intellectual disabilities. I was always struck by the ways people tended to “act out”—especially in self-harming ways—when they were experiencing some kind of internal struggle they couldn’t communicate, some kind of trauma they felt trapped—alone—inside. And over the many years I worked with kids and adults with physical and intellectual disabilities, I saw a lot of self-harm—biting of hands, scratching of faces, bashing of heads—that seemed to extend from the same situation: “I need something. I don’t have the language to express what I need. And you aren’t listening to me.”

I landed on this particular diagnostic terminology for the title of my novel because it has always seemed so oddly judge-y to me, such an apt embodiment of that failure to communicate. And this seems like the kind of judgment that people cast upon others when they aren’t listening when they aren’t considering the complexities of peoples’ needs. It’s the kind of judgment cast both upon people (who are struggling with issues of illness and disability) and places like the Coal Region (which are themselves—in many ways—suffering from a kind of terminal sickness). I guess one of my primary hopes for this novel is that it embodies the emotional and sensory experiences of this sickness, that it helps readers investigate these kinds of judgments (and—perhaps, in a more abstract sense—to inhabit those judgments along with these characters).

GM: We noticed that in your novel and in your short story collection, All of Your Most Private Places, that space and setting are very important in mirroring the conflicts that the characters face. Can you say a bit more about what made you choose Pennsylvania coal towns as the setting for Failure to Thrive?

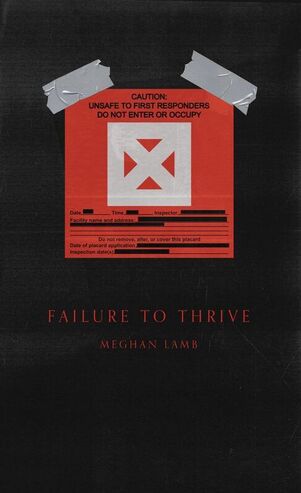

ML: I started writing Failure to Thrive in 2014, at the very beginning of my marriage to a person who has family members from the PA Coal Region (we’re now in the process of getting a divorce). When he first drove me through the coal towns that inspired my novel’s setting—Shamokin, Coal Township, Mt. Carmel, the evacuated scar of Centralia—I was so struck by them, their singular blend of beauty and dilapidation (the coal-streaked clapboard, the once resplendent buildings in various states of ruination, the houses with X signs on the front doors indicating to first responders that it was unsafe to enter). I was also struck by this weird, uncanny feeling that I’d been there before (even though I hadn’t been), perhaps triggered by associations with my family’s hometown of Decatur, IL (another once-thriving industrial city now on the decline). The landscape looked sick. The buildings looked sick. The roads looked sick. There were signs on the homes that said, “Danger, oxygen in use.” I was just filled with this sense of wonder about the people who lived there, who stayed there, who couldn’t leave because of barriers related to illness and disability.

When I began this novel, I think I was trying to map my experiences working as a caregiver for elders and people with disabilities in the Midwest onto my imagination of life in these Pennsylvania towns that were really important to my (then) husband. As time went on, though—and as our marriage started to reveal its hairline cracks, its sickness, so to speak—I think I was writing more and more toward my own increasing sensation of being “stuck,” of being cloistered with this person I felt loyal to, but ultimately disconnected from (as so many people feel, living in these kinds of towns: part of them probably knows that these towns are dying, that they’re not going to experience some miraculous recovery, but these towns are “home”…to the degree that “home” itself perhaps becomes aligned with a kind of sickness, a kind of sick-glazed mental fog).

I guess it’s hard to say what made me “choose” this place as the setting for my novel because my feelings toward the place (and my relationship with the place) changed so much as I was writing it. In some ways, it’s kind of like asking a divorcing couple why they chose to be together. Even if you can remember what originally drew you together, it becomes more and more difficult to articulate as you investigate and interrogate that relationship in your imagination.

ML: I started writing Failure to Thrive in 2014, at the very beginning of my marriage to a person who has family members from the PA Coal Region (we’re now in the process of getting a divorce). When he first drove me through the coal towns that inspired my novel’s setting—Shamokin, Coal Township, Mt. Carmel, the evacuated scar of Centralia—I was so struck by them, their singular blend of beauty and dilapidation (the coal-streaked clapboard, the once resplendent buildings in various states of ruination, the houses with X signs on the front doors indicating to first responders that it was unsafe to enter). I was also struck by this weird, uncanny feeling that I’d been there before (even though I hadn’t been), perhaps triggered by associations with my family’s hometown of Decatur, IL (another once-thriving industrial city now on the decline). The landscape looked sick. The buildings looked sick. The roads looked sick. There were signs on the homes that said, “Danger, oxygen in use.” I was just filled with this sense of wonder about the people who lived there, who stayed there, who couldn’t leave because of barriers related to illness and disability.

When I began this novel, I think I was trying to map my experiences working as a caregiver for elders and people with disabilities in the Midwest onto my imagination of life in these Pennsylvania towns that were really important to my (then) husband. As time went on, though—and as our marriage started to reveal its hairline cracks, its sickness, so to speak—I think I was writing more and more toward my own increasing sensation of being “stuck,” of being cloistered with this person I felt loyal to, but ultimately disconnected from (as so many people feel, living in these kinds of towns: part of them probably knows that these towns are dying, that they’re not going to experience some miraculous recovery, but these towns are “home”…to the degree that “home” itself perhaps becomes aligned with a kind of sickness, a kind of sick-glazed mental fog).

I guess it’s hard to say what made me “choose” this place as the setting for my novel because my feelings toward the place (and my relationship with the place) changed so much as I was writing it. In some ways, it’s kind of like asking a divorcing couple why they chose to be together. Even if you can remember what originally drew you together, it becomes more and more difficult to articulate as you investigate and interrogate that relationship in your imagination.

|

GM: Failure to Thrive is structured in three separate, but interwoven parts. How did you decide on this format for your novel? Did you originally intend for there to be more or fewer characters in the overarching narrative of the coal town?

ML: I know this is a boring answer, but the three-part structure and the number of characters were something I’d planned from the very beginning. I tend to spend almost as much time planning a writing project as I do actually writing it, so all of my choices are very deliberate and pre-outlined. Before I wrote the novel, I literally had 90 pages worth of outlined notes with all the major “moves” each section was going to make, and I just kind of filled in that outline. I changed things a bit as I went through the novel, but I think I needed that level of visual outlining to see where repeated gestures, images, and phrases needed to be. The only parts of the novel I didn’t write chronologically were the frame sections. I conceived of those sections in the process of evaluating what this novel meant to me—where I saw “myself” (and situated my own outsiderly subjectivities) within the novel—as I was writing it. I also conceived of those sections after visiting all these spaces in person—the evacuated ghost town of Centralia, the former J.W. Cooper School, and the graffitied shells of Concrete City—and feeling haunted by them, feeling like they deserved their own place in the book. |

"But these towns are "home"... to the degree that "home" itself perhaps becomes aligned with a kind of sickness, a kind of sick-glazed mental fog." |

GM: With Failure to Thrive, the setting plays a large role in unifying the three narratives, but the town was left unnamed. What led to this decision?

ML: Part of that decision stems from the aforementioned connection I felt between the Coal Region and Decatur…and even with other places I’d been to in Eastern Europe. I wanted there to be this sense that it was everywhere, anywhere, and nowhere, while also being in a very specific place (if that makes any sense). So, I left the town nameless in the interest of making it more blendy. It’s actually an amalgam of several towns and references different spaces in different towns. Blending the towns allowed me to pay homage to all the different spaces that struck me, intrigued me, and haunted me.

GM: Failure to Thrive tackles tough topics like addiction, disability, illness, and death. You’ve stated before that your novella, Silk Flowers, was written during a nine-month period where your left leg mysteriously stopped working. Did this experience also influence your choice in subject matter for Failure to Thrive? How did you prepare for writing on these topics?

ML: That experience—of personally dealing with a disability—changed my perspective for the rest of my life. I don’t self-identify as a person with a disability or a disabled person—because the disability itself wasn’t chronic, but liminal—but I went through a major paradigm shift, going to all these doctors who couldn’t tell me what caused my “idiopathic neuropathy,” who couldn’t tell me when or even if my leg would ever function normally again. That experience of fear and uncertainty changed me in profound ways…the experience of learning to live with and within that fear and uncertainty, the weird dual sensation of, “I don’t know what’s happening,” and “my body has already decided what’s going to happen.” I suppose that’s part of the driving ethos behind Failure to Thrive, this curiosity about—and desire to write toward the imagined experiences of—others who feel both unsure and grimly certain of what the future might bring.

ML: Part of that decision stems from the aforementioned connection I felt between the Coal Region and Decatur…and even with other places I’d been to in Eastern Europe. I wanted there to be this sense that it was everywhere, anywhere, and nowhere, while also being in a very specific place (if that makes any sense). So, I left the town nameless in the interest of making it more blendy. It’s actually an amalgam of several towns and references different spaces in different towns. Blending the towns allowed me to pay homage to all the different spaces that struck me, intrigued me, and haunted me.

GM: Failure to Thrive tackles tough topics like addiction, disability, illness, and death. You’ve stated before that your novella, Silk Flowers, was written during a nine-month period where your left leg mysteriously stopped working. Did this experience also influence your choice in subject matter for Failure to Thrive? How did you prepare for writing on these topics?

ML: That experience—of personally dealing with a disability—changed my perspective for the rest of my life. I don’t self-identify as a person with a disability or a disabled person—because the disability itself wasn’t chronic, but liminal—but I went through a major paradigm shift, going to all these doctors who couldn’t tell me what caused my “idiopathic neuropathy,” who couldn’t tell me when or even if my leg would ever function normally again. That experience of fear and uncertainty changed me in profound ways…the experience of learning to live with and within that fear and uncertainty, the weird dual sensation of, “I don’t know what’s happening,” and “my body has already decided what’s going to happen.” I suppose that’s part of the driving ethos behind Failure to Thrive, this curiosity about—and desire to write toward the imagined experiences of—others who feel both unsure and grimly certain of what the future might bring.

GM: Failure to Thrive leaves some things open-ended and implied. Helen’s drug addiction is never directly addressed. Jack’s past is still a big mystery. How do you decide when to leave things more ambiguous instead of providing concrete conclusions?

ML: That decision-making process is actually pretty easy for me. If I’m not particularly interested in a detail or a bit of backstory—or, more to the point, if I don’t feel like the particular story I’m telling is interested in it—I don’t include it. The novel lightly gestures toward issues in Helen and Jack’s backgrounds that lead them to where they are in the narrative “now,” but I think the real story resides in the now for those two characters, so that’s what I chose to focus on.

Part of the ethos behind that focus on the now is also my own resistance to the nostalgia that’s so present—and such a defining force—in most stories I’ve read of this area. While I appreciate the beauty of what these Coal Region spaces once were, as well as the potency of that nostalgia, I think it’s important to focus on the now in an honest way and to appreciate that for what it is rather than turning away from it.

GM: In Failure to Thrive, there are several instances of unconventional arrangement of the words to emphasize certain feelings or images. Where in your writing process did these arrangements come to be? Were any parts of the plot added to allow for this structure?

ML: That decision-making process is actually pretty easy for me. If I’m not particularly interested in a detail or a bit of backstory—or, more to the point, if I don’t feel like the particular story I’m telling is interested in it—I don’t include it. The novel lightly gestures toward issues in Helen and Jack’s backgrounds that lead them to where they are in the narrative “now,” but I think the real story resides in the now for those two characters, so that’s what I chose to focus on.

Part of the ethos behind that focus on the now is also my own resistance to the nostalgia that’s so present—and such a defining force—in most stories I’ve read of this area. While I appreciate the beauty of what these Coal Region spaces once were, as well as the potency of that nostalgia, I think it’s important to focus on the now in an honest way and to appreciate that for what it is rather than turning away from it.

GM: In Failure to Thrive, there are several instances of unconventional arrangement of the words to emphasize certain feelings or images. Where in your writing process did these arrangements come to be? Were any parts of the plot added to allow for this structure?

|

ML: For me, as odd as it sounds, language and plot aren’t divisible from one another. Language is a storytelling engine. Sometimes the story is the language. The language is what happens.

To be a little less finger-wavey about it: I conceived of some of those odd textual arrangements—particularly, the italic “voice-of-the-underground-fire” frame sections—when I was doing a series of little exercises to help myself reconnect with the book. I was taking quoted sections from the novel and making weird, recycled prose poems from them, just playing around with stuff, seeing if changing the formatting of these words would change my perspective on them. I ended up really liking what I was doing in those weird prose poems (or whatever they were), so I developed those into the frame sections that are now in the book. Not all of the weird stuff came about so intentionally, however. Sometimes, the weird way I write something is just the way that happens to feel most right. I wish I could deconstruct my process more clearly than that, but sometimes I simply can’t! |

"That experience of fear and uncertainty changed me in profound ways…the experience of learning to live with and within that fear and uncertainty, the weird dual sensation of, “I don’t know what’s happening,” and “my body has already decided what’s going to happen.” |

GM: In an interview with Pank Magazine, you stated, “Everything bleeds into everything and fiction is just this funny desperate little attempt to staunch the bleeding.” As a nonfiction editor for Nat. Brut, how do you feel that fiction and nonfiction differ in this regard? Where do you find overlap?

ML: The older I get, the less confident I feel defining the differences between fiction and nonfiction, and between fiction and poetry, for that matter. I’ve had several encounters with friendly strangers and writerly acquaintances who’ve greeted me with something to the effect of, “oh, you’re one of my favorite poets,” and while that’s very sweet and flattering, I’m not sure what they’re referring to when they compliment my poetry. Are they referring to the weird ellipses and fragmentations in Silk Flowers? Or the pieces of micro-fiction in my collection? Or the hybridity of my writing, the list-y gestures, or something like that? I couldn’t begin to say. I tend to think of everything I write as fiction, but that isn’t a conscious aesthetic or intellectual choice, really, especially these days. When I was younger, I really wanted to write fiction—I really wanted to be a fiction writer in the vein of other writers I loved—but now that I’m culling through my internal readerly archives and making syllabi for fiction courses, I’m struck more than ever by how blurry those lines really are. Like Yasunari Kawabata’s Palm of the Hand stories. Are those fiction? Poetry? Microfiction? Are some of them even a kind of mini-memoir? I think all of those descriptions fit, but I’m not quite sure what kind of question these descriptions satisfy if that makes any sense.

As an editor, I tend to admire pieces that inhabit in-between spaces—that seem like hybrids of multiple narrative genres—and I’m sure that’s evident in the writers I feature in the magazine: Dao Strom, Seo-Young Chu, Joanna C. Valente, Wendy C. Ortiz, Claire Donato, Alistair McCartney, Julia Cohen. Many of these writers are poets cum nonfiction writers, or fiction writers cum nonfiction writers, and/or just hybrid writers writing toward a subject they happen to feel like identifying as nonfiction.

ML: The older I get, the less confident I feel defining the differences between fiction and nonfiction, and between fiction and poetry, for that matter. I’ve had several encounters with friendly strangers and writerly acquaintances who’ve greeted me with something to the effect of, “oh, you’re one of my favorite poets,” and while that’s very sweet and flattering, I’m not sure what they’re referring to when they compliment my poetry. Are they referring to the weird ellipses and fragmentations in Silk Flowers? Or the pieces of micro-fiction in my collection? Or the hybridity of my writing, the list-y gestures, or something like that? I couldn’t begin to say. I tend to think of everything I write as fiction, but that isn’t a conscious aesthetic or intellectual choice, really, especially these days. When I was younger, I really wanted to write fiction—I really wanted to be a fiction writer in the vein of other writers I loved—but now that I’m culling through my internal readerly archives and making syllabi for fiction courses, I’m struck more than ever by how blurry those lines really are. Like Yasunari Kawabata’s Palm of the Hand stories. Are those fiction? Poetry? Microfiction? Are some of them even a kind of mini-memoir? I think all of those descriptions fit, but I’m not quite sure what kind of question these descriptions satisfy if that makes any sense.

As an editor, I tend to admire pieces that inhabit in-between spaces—that seem like hybrids of multiple narrative genres—and I’m sure that’s evident in the writers I feature in the magazine: Dao Strom, Seo-Young Chu, Joanna C. Valente, Wendy C. Ortiz, Claire Donato, Alistair McCartney, Julia Cohen. Many of these writers are poets cum nonfiction writers, or fiction writers cum nonfiction writers, and/or just hybrid writers writing toward a subject they happen to feel like identifying as nonfiction.

"You can hide behind invention. You can draw a character and hide within that character, draw some imaginary house, and peek out at everyone from the fake dark closet of the fake dark bedroom of the fake dark house. But when you’re inventing—when you’re “making things up”—you’re exposing the seams of your imagination." |

But I think your question is a worthwhile one to explore, and I don’t want to let myself off the hook, here. In the interest of identifying nonfiction versus fiction ethos: perhaps nonfiction has some obligation to clearly articulate the narrator’s perspective, why they’re telling what they’re telling, perhaps even some impulse toward self-exposure that’s essential to what it is. And while fiction is self-exposing as well, that exposure doesn’t draw as much attention to itself. You can hide behind invention. You can draw a character and hide within that character, draw some imaginary house, and peek out at everyone from the fake dark closet of the fake dark bedroom of the fake dark house. But when you’re inventing—when you’re “making things up”—you’re exposing the seams of your imagination. And as you get older and older, the more and more you write, you expose your obsessions. You expose patterns in the stories you’re telling—in the stories you’re telling over and over and over again—and, if readers pay close attention, they can start to assemble those patterns into the shape of a real person. Maybe that’s its own kind of nonfiction.

|

Read more about Lamb's work at her website

Read our review of Failure to Thrive by Associate Editor Ariana Tucker

Read our review of Failure to Thrive by Associate Editor Ariana Tucker