Interview

The book that almost wasn't: AN INTERVIEW WITH Mitchell Fink

BY Patricia Dove & Elaine Paliatsas-Haughey

2016

People believe that time will heal the racial divides in America; however, it is only when people change the way they think and look at the world that racism will eventually be stopped. It has to start with a change of heart.

|

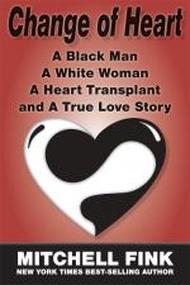

In his most recent publication, Change of Heart, honored journalist Mitchell Fink tells the story of Robert Dunn. Dunn grew up in an all-white neighborhood in Queens during the 60's and resented white people for the way they treated him. In the spring of 1998 Dunn received a heart transplant, but at the time he didn't know that the heart would be from Dorothy Moore, a white woman, and that it would forever change his view on race. Fink and Dunn teamed up to write this book; however, just as their agent began shopping it to publishers, Dunn had a heart attack and passed away. Eventually, Fink decided to move forward with his effort and finish this book for Dorothy Moore and Robert Dunn.

|

Glassworks Magazine (GM): Change of Heart speaks to the possibility that all of us, even the most hardened, might be able to change our views about racism. How does this story attempt to convey the message of promoting acceptance across races, and what motivated you in to write it?

Mitchell Fink (MF): My first interest as a journalist is always the story. Is it a compelling story, and will others relate to it? That's always the test. In the case of Robert Dunn, I felt that if he could change his long-held views, and suddenly become more tolerant of whites, then perhaps there was a chance that others might become more tolerant of any race not their own.

GM: Racism has seemingly worsened over time. George Zimmerman, the riots in Ferguson and the list goes on. Every time a police officer shoots someone, the first thing considered is the race of the cop and the race of person. If the cop is white and the person is black it no longer matters what the person did to get shot, it matters about the race and the chaos begins all over again. What do you believe society can do to combat this?

MF: Accountability would be a good place to start. We live in a different world today. Everyone is watching. Brutality on the part of law enforcement will be caught on camera for all to see. The kid in a hooded sweatshirt robbing a convenience store will be caught on camera for all to see. Both have to be accountable. The absentee father has to be accountable. The drug dealer in the projects. The gangs. The gun owner. The gun manufacturer. The elected official. As a law-abiding citizen, I condemn them all, black and white. And if Robert Dunn were still here, I believe he'd say the exact same thing.

Mitchell Fink (MF): My first interest as a journalist is always the story. Is it a compelling story, and will others relate to it? That's always the test. In the case of Robert Dunn, I felt that if he could change his long-held views, and suddenly become more tolerant of whites, then perhaps there was a chance that others might become more tolerant of any race not their own.

GM: Racism has seemingly worsened over time. George Zimmerman, the riots in Ferguson and the list goes on. Every time a police officer shoots someone, the first thing considered is the race of the cop and the race of person. If the cop is white and the person is black it no longer matters what the person did to get shot, it matters about the race and the chaos begins all over again. What do you believe society can do to combat this?

MF: Accountability would be a good place to start. We live in a different world today. Everyone is watching. Brutality on the part of law enforcement will be caught on camera for all to see. The kid in a hooded sweatshirt robbing a convenience store will be caught on camera for all to see. Both have to be accountable. The absentee father has to be accountable. The drug dealer in the projects. The gangs. The gun owner. The gun manufacturer. The elected official. As a law-abiding citizen, I condemn them all, black and white. And if Robert Dunn were still here, I believe he'd say the exact same thing.

"We live in a different world today. Everyone is watching. Brutality on the part of law enforcement will be caught on camera for all to see. The kid in a hooded sweatshirt robbing a convenience store will be caught on camera for all to see. Both have to be accountable."

GM: You write that Dunn developed a fear after finding out his donor was a white woman. How do you think this fear is connected to the current civil rights renaissance occurring across the country?

MF: I don't think there's necessarily a civil rights renaissance occurring across the country. In many ways the issue has never gone away. His fear was simply that the donor's family would regard him with the same kind of contempt other whites showed him throughout his childhood. His fear was completely understandable given how he was treated by whites in the 1960s.

GM: What is it about Robert's personal story that sparks discussions about race in a time of volatile police brutality and #BlackLivesMatter?

MF: If Robert Dunn, one of the most opinionated, belligerent and angry people I have ever known, can change, anyone is capable of changing. This was a man who was about to throw a Molotov cocktail at a wooden police shack in Nassau County, Long island. Robert and his cousin hid one night in a nearby brush making these crude homemade grenades that would explode on impact. They weren't trying to kill anyone. They just wanted to destroy the shack because of what it represented. As they were preparing their crude explosive devices, two cops walking nearby heard them. The cops mistakenly thought they were two homosexuals about to have sex, and chased them away. If the cops hadn't happened upon them, they definitely would have blown up the shack. This was also the same man who just a few short years later cried his eyes out at the kindness and love shown to him by the donor's white family. If that's not change, I don't know what is.

GM: You became like a brother to Robert Dunn and have said that even after his death you have stayed close with his and Dorothy's families. From that vantage point, what do you think they would have to say about current events like those in Ferguson and Baltimore?

MF: Robert Dunn would be just as angry today as he was back then. He would be protesting in Ferguson and in Baltimore. Finding a cure for injustice, any injustice, against anyone, was always what mattered most to him. I don't think he would have approved of the Ferguson riots. He would have understood the motivation behind the riots, but because he had become a trusted attorney in the black community, I feel he might he might have gone there as a voice of reason. I haven't asked Dorothy's family what they thought of Ferguson or Baltimore. It certainly couldn't have made them happy. They are wonderful, thoughtful, loving people, and colorblind when it comes to race.

MF: I don't think there's necessarily a civil rights renaissance occurring across the country. In many ways the issue has never gone away. His fear was simply that the donor's family would regard him with the same kind of contempt other whites showed him throughout his childhood. His fear was completely understandable given how he was treated by whites in the 1960s.

GM: What is it about Robert's personal story that sparks discussions about race in a time of volatile police brutality and #BlackLivesMatter?

MF: If Robert Dunn, one of the most opinionated, belligerent and angry people I have ever known, can change, anyone is capable of changing. This was a man who was about to throw a Molotov cocktail at a wooden police shack in Nassau County, Long island. Robert and his cousin hid one night in a nearby brush making these crude homemade grenades that would explode on impact. They weren't trying to kill anyone. They just wanted to destroy the shack because of what it represented. As they were preparing their crude explosive devices, two cops walking nearby heard them. The cops mistakenly thought they were two homosexuals about to have sex, and chased them away. If the cops hadn't happened upon them, they definitely would have blown up the shack. This was also the same man who just a few short years later cried his eyes out at the kindness and love shown to him by the donor's white family. If that's not change, I don't know what is.

GM: You became like a brother to Robert Dunn and have said that even after his death you have stayed close with his and Dorothy's families. From that vantage point, what do you think they would have to say about current events like those in Ferguson and Baltimore?

MF: Robert Dunn would be just as angry today as he was back then. He would be protesting in Ferguson and in Baltimore. Finding a cure for injustice, any injustice, against anyone, was always what mattered most to him. I don't think he would have approved of the Ferguson riots. He would have understood the motivation behind the riots, but because he had become a trusted attorney in the black community, I feel he might he might have gone there as a voice of reason. I haven't asked Dorothy's family what they thought of Ferguson or Baltimore. It certainly couldn't have made them happy. They are wonderful, thoughtful, loving people, and colorblind when it comes to race.

|

GM: Do you believe that this story of Dunn and Moore may show people the way towards racial healing?

MF: I realize this may sound like an author only wanting to spin a good story, but Robert was so deeply moved by his donor's background and story. Once Robert learned how difficult Dorothy's life had been, he felt this overwhelming emotional need to protect her. He began a dialogue with her oldest child, mentoring him and advising him as though he were his. This also filled a need in Robert, although for too short a time, to experience himself as a father. So in the process of protecting Dorothy, and her heart, he began falling in love with her. Although that was impossible in a physical sense, emotionally he was in love. So much so, in fact, that during his last days, when he was faced with the life-saving choice of a mechanical heart transplant followed by another human heart transplant, he refused. He died protecting Dorothy Moore, right up to the end. He was just turning 50, but it was no longer necessary for him to stick around. He was healed. |

GM: In the introduction to your book you wrote "Robert's life was not the selfless act of a pre-teen, but rather the powerful, complex and racially charged set of circumstances that preceded his death. Change of Heart is the story of those circumstances and how one man's decision to confront his darkest fears and twisted beliefs made it possible for him to find the most unique kind of unconditional love, a love that could only be experienced from the inside out." What do you believe or hope that people take away from this story? What do you wish the moral to be?

MF: The "selfless act" I mention had to do with Robert as a young boy running into a burning building and saving a few young children who were trapped by themselves with no adult around. Someone who spoke at his funeral described the scene as "the defining moment" of Robert's life. And I maintain that the real defining moment of his life was the true change of heart he experienced in the last year of his life. What I hope people take away from this story is this: Our ethnicity and skin color may be different. We come from different countries, different backgrounds, and different stations in life. We're rich, poor, broken, aggressive, passive, lucky and unlucky. But our hearts, it turns out, are interchangeable.

MF: The "selfless act" I mention had to do with Robert as a young boy running into a burning building and saving a few young children who were trapped by themselves with no adult around. Someone who spoke at his funeral described the scene as "the defining moment" of Robert's life. And I maintain that the real defining moment of his life was the true change of heart he experienced in the last year of his life. What I hope people take away from this story is this: Our ethnicity and skin color may be different. We come from different countries, different backgrounds, and different stations in life. We're rich, poor, broken, aggressive, passive, lucky and unlucky. But our hearts, it turns out, are interchangeable.