Interview

Ritmo Y Poesia: aN INTERVIEW WITH Dra. Raina J. LeÓn

BY Rebecca Green, Iliana Pineda, Nyds Rivera, & Paige Stressman

March 2023

|

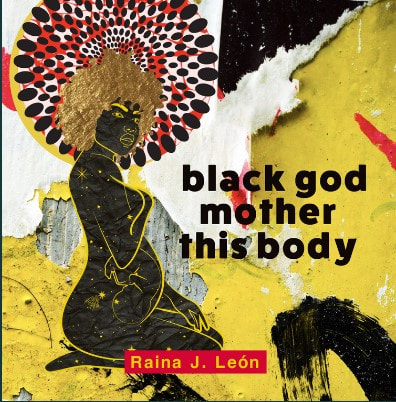

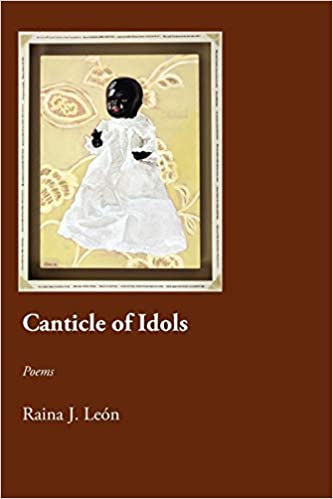

Identity is a theme central to contemporary poetry, especially in recent years. Dra. Raina J. León, a local Philly poet, has explored many aspects of her life over her nearly two decades of writing poetry. From her religious upbringing in Canticle of Idols to her reflections on motherhood in her most recent collection, black god mother this body, León has built her career on the art of self-exploration. Proudly Afro-Boricua, León’s poetry encapsulates the rhythms of her culture and combines them with the soul of Philadelphia.

In this interview, León talks about her cultural and familial influences, her work as a founding editor for The Acentos Review, her forthcoming release of an audio poetry collection, and, of course, the importance of music, rhythm, and la cultura in her poetry. |

Glassworks Magazine (GM): As writers, it can be hard to look back at older work because of how overcritical of ourselves we can be. You have worked on the release of your audio re-imagining of your first published poetry collection, Canticle of Idols (2008). What inspired you to begin the process and how has the experience been, returning to the poems in the Canticle of Idols?

Raina J. León (RJL): Over the years, I’ve rarely read from Canticle at readings, but when I do, I have found myself standing in such gratitude and wonder for the poet me of that time. There are thematic considerations, idea threads, dreams, revelations that still course through my work.

About a year ago, I reached out to the original publisher about purchasing the rights back so that I might re-imagine the book. Not many authors choose to have their books go out of print, but in my case, I didn’t need the book to remain available. It’s been out in the world for nearly 15 years, and since then I have had my work published in anthologies, full collections, chapbooks, even as a virtual reality enriched poetry film! I thought to myself, what would it be to work with another artist collaboratively on creating poetic soundscapes?

And so I reached out to Cinthia “E” Pimentel who was the producer for a Poetry Foundation podcast episode I was a collaborator on with Jasmine Mendez and Darrel Alejandro Holnes. E was a dream to work with, and I had been pondering how we might collaborate again ever since, so I reached out to them about doing an ebook. E was the one who pushed forward the idea of doing an album, and it was a WONDER! In celebration, I also had trusted community members, Urayoán Noel, Rich Villar, Peggy Robles-Alvarado, and Grisel Y. Acosta, listen to the tracks and offer some insight into them while also creating their own work in response. It was an evening of magic!

(GM): Would you do it again with another collection of your poetry, or even a new collection?

(RJL): Absolutely! I’m also planning to integrate some of the pieces into my current book, black god mother this body, as I’ve committed to changing the augmented reality content seasonally. Let me back up. The new book has augmented reality cuing images meaning that if you use the app, Halo AR, and hold it towards the digital collages in my book, pop! You’ll see or hear new content! Sometimes it will directly relate to the collage, sometimes it will be an audio contribution, sometimes an interview, sometimes a 3-D visualization of an altar. I’m thinking about integrating some of the audio versions of my poems into poetry films that would pop up when a person interacts with black god mother this body.

Raina J. León (RJL): Over the years, I’ve rarely read from Canticle at readings, but when I do, I have found myself standing in such gratitude and wonder for the poet me of that time. There are thematic considerations, idea threads, dreams, revelations that still course through my work.

About a year ago, I reached out to the original publisher about purchasing the rights back so that I might re-imagine the book. Not many authors choose to have their books go out of print, but in my case, I didn’t need the book to remain available. It’s been out in the world for nearly 15 years, and since then I have had my work published in anthologies, full collections, chapbooks, even as a virtual reality enriched poetry film! I thought to myself, what would it be to work with another artist collaboratively on creating poetic soundscapes?

And so I reached out to Cinthia “E” Pimentel who was the producer for a Poetry Foundation podcast episode I was a collaborator on with Jasmine Mendez and Darrel Alejandro Holnes. E was a dream to work with, and I had been pondering how we might collaborate again ever since, so I reached out to them about doing an ebook. E was the one who pushed forward the idea of doing an album, and it was a WONDER! In celebration, I also had trusted community members, Urayoán Noel, Rich Villar, Peggy Robles-Alvarado, and Grisel Y. Acosta, listen to the tracks and offer some insight into them while also creating their own work in response. It was an evening of magic!

(GM): Would you do it again with another collection of your poetry, or even a new collection?

(RJL): Absolutely! I’m also planning to integrate some of the pieces into my current book, black god mother this body, as I’ve committed to changing the augmented reality content seasonally. Let me back up. The new book has augmented reality cuing images meaning that if you use the app, Halo AR, and hold it towards the digital collages in my book, pop! You’ll see or hear new content! Sometimes it will directly relate to the collage, sometimes it will be an audio contribution, sometimes an interview, sometimes a 3-D visualization of an altar. I’m thinking about integrating some of the audio versions of my poems into poetry films that would pop up when a person interacts with black god mother this body.

(GM): In ¡Manteca!: An Anthology of Afro-Latin@ Poets, your poem “Two Pounds, Night Sky Notes,” combines music and poetry in a physical way by including bar lines and music notes. Of course, it’s impossible not to draw parallels between the two forms, but we wonder what inspired you to blend poetry and music in your published work? Are you also a musician, and if so, how do you think your experiences as such have influenced your work?

(RJL): I grew up playing the clarinet from elementary and secondary school, and started singing in choirs when I was around 14 and was even a part of a touring choir in college. I took up the cello in high school and then returned to it and picked up the piano as an adult… all that to say, I’m an amateur to intermediate musician, depending on the instrument. I’m always fascinated by forms and how different art forms can influence one another.

Cedar Sigo, in a workshop I took during my MFA, talked about how the page can function as a score for the poem and that remains so resonant to me. I was studying with him when that poem was written and wanted to explore how the poem could contain grief and represent the breath of both the speaker within the poem and the reader of the poem.

(RJL): I grew up playing the clarinet from elementary and secondary school, and started singing in choirs when I was around 14 and was even a part of a touring choir in college. I took up the cello in high school and then returned to it and picked up the piano as an adult… all that to say, I’m an amateur to intermediate musician, depending on the instrument. I’m always fascinated by forms and how different art forms can influence one another.

Cedar Sigo, in a workshop I took during my MFA, talked about how the page can function as a score for the poem and that remains so resonant to me. I was studying with him when that poem was written and wanted to explore how the poem could contain grief and represent the breath of both the speaker within the poem and the reader of the poem.

"I am a poet who is profoundly engaged with sound...Even my most experimental work incorporates a keen attunement to the sonic work on the page." |

All that aside, I am a poet who is profoundly engaged with sound. I edit my work through reading it aloud as there are rhythms that I have come to experience as conveyors of emotional resonance, rhythms that I intuitively use as the best vehicles for sharing narrative. Even my most experimental work incorporates a keen attunement to the sonic work on the page. The work is meant to exist within the mind, within the internal voice of the reader, and as a performative text. Much of my work could even be said to summon the spiritualized rhythms of the sermon, the psalm, or hymn … but I won’t tell you which ones. I grew up immersed in storytelling and art and religious praxis, culturally enriched, and so all of it comes into my work … and there’s also always a bit of play, even in the most somber of poems.

|

(GM): As we can see with your poems “Southwest Philadelphia, 1988” and “Banned Portrait in the MAGA Era: Study Says Black Girls are ‘Less Innocent,’” you write often about your experiences living in Philly. Do you feel that Philadelphia, as much as your cultural background, has influenced your writing content, style, and form?

(RJL): I am a Philadelphian. Through and through. It’s in my bio, and I rep my city hard. I love the cheeky trickster, the resolute devotion in the city, the boundless love, the inventiveness and creation, the defiance of rules, this history and the futurist visions, tension between power and freedom that seems to be imprinted on the cobblestones, the art, and the wonder! All of that is in my work and in me. I’ve lived many places, taken many paths, felt myself grounded in communities I deeply love and return to, and Philly has always been the site where my heart returns.

(GM): We’ve noticed that much of your work, specifically that of your recent volume of poetry, black god mother this body, focuses on family affinities and the complicated relationships you have with some of your family members. What made you decide to write about these relationships and how has your relationship with them played a role in the recurring themes of your work?

(RJL): Complexity is life, and my work, even when it is mourning, is also reaching towards life, yearning towards light. For my family, those chosen and in legacy, I am the most loyal devotee. Even in the most difficult stories, part of the work of the writing is about healing, about not turning away from complexities.

Think of a treasure in a field. Some might dig with a single purpose: find the treasure. And some of those might get tired and give up along the way. I’m the person that says, there is a treasure in this field, and I will dig and dig, finding wonder in the rock, and worm in its work, and in the detritus of generations that made the field. I might never find the gold that I thought I was on my way towards. I might stop and look around, but that ceasing would be different than the person who digs and gives up.

No, my stopping would be that of recognizing that the treasure is the field, all the layers, the hiding, and the knowledge that somewhere there is gold below and it may also be within. It’s in the interconnections of the field that I will never discover and respect as hidden and still beautiful and worthy of their autonomy in the quiet beneath. I write about family to see the field of them and myself in relationship to them. I write to see us in the continuity of times (plural on purpose), the overlapping spirality of time where the past is always still happening and the future is playing out in the actions of the present. I write, because I love enough to see relational layers.

(RJL): I am a Philadelphian. Through and through. It’s in my bio, and I rep my city hard. I love the cheeky trickster, the resolute devotion in the city, the boundless love, the inventiveness and creation, the defiance of rules, this history and the futurist visions, tension between power and freedom that seems to be imprinted on the cobblestones, the art, and the wonder! All of that is in my work and in me. I’ve lived many places, taken many paths, felt myself grounded in communities I deeply love and return to, and Philly has always been the site where my heart returns.

(GM): We’ve noticed that much of your work, specifically that of your recent volume of poetry, black god mother this body, focuses on family affinities and the complicated relationships you have with some of your family members. What made you decide to write about these relationships and how has your relationship with them played a role in the recurring themes of your work?

(RJL): Complexity is life, and my work, even when it is mourning, is also reaching towards life, yearning towards light. For my family, those chosen and in legacy, I am the most loyal devotee. Even in the most difficult stories, part of the work of the writing is about healing, about not turning away from complexities.

Think of a treasure in a field. Some might dig with a single purpose: find the treasure. And some of those might get tired and give up along the way. I’m the person that says, there is a treasure in this field, and I will dig and dig, finding wonder in the rock, and worm in its work, and in the detritus of generations that made the field. I might never find the gold that I thought I was on my way towards. I might stop and look around, but that ceasing would be different than the person who digs and gives up.

No, my stopping would be that of recognizing that the treasure is the field, all the layers, the hiding, and the knowledge that somewhere there is gold below and it may also be within. It’s in the interconnections of the field that I will never discover and respect as hidden and still beautiful and worthy of their autonomy in the quiet beneath. I write about family to see the field of them and myself in relationship to them. I write to see us in the continuity of times (plural on purpose), the overlapping spirality of time where the past is always still happening and the future is playing out in the actions of the present. I write, because I love enough to see relational layers.

|

(GM): Along with family affairs, writers focus more on external factors — like discrimination and oppression — while describing the experience of racism in America. In your poem “blackety black black solstice cleave” from your most recent release in black god mother this body (2022), you explore the idea of internalized racism. Has writing about this topic impacted the way you view your culture and identity? Has it been empowering?

(RJL): That piece is one of the most entangled and self-revelatory pieces I’ve ever written. It’s definitely helped me to explore internalized racism, misogyny in the interpersonal, loss, and forgiveness while also helping me to think about the mothering I want to do, what I was offered in my own becoming, what I want to preserve, and what I want to leave behind. It has been empowering, because in that piece I also do a close reading of a key mothering relationship I had, for the good and the bad of it, and there’s so much love and healing in that reckoning. Generosity is a word that appears in it several times, and I hope that those who read it also find the generosity and kindness is reflective. |

(GM): Through our own experiences with poetry, we've noticed that Latinx poets tend to have a very lyrical, musical quality to their work. Your work is no exception to this, incorporating similar musical and rhythmic techniques. Can you speak about the intersection between culture and writing style? Do you think that your culture, identity, and upbringing have had a part to play in the development of your own style?

(RJL): When I think about my people, I have such pride. It’s in our music, our fervor, our connection to otherworldliness, our political engagement, our defiance, our embodied attunement to the rhythms of the world (hips that move with the grace of palm trees and waves), the portal opening of the sound of the coquí echoing in our ears perhaps even an extended measure upon measure playing in the blood. Boricua. Soy boricua and diasporican, and I have grown up listening to stories of angels and brujas, orishas and labor organizers, santos and the origins of Latin jazz. And Papi came up also in full recognition and celebration of his blackness, which was not universally understood in my family, let alone the Puerto Rican community, and it’s still not. Still, all of the cultural traditions and practices that inform who we are and who I am come through in my work. How could it not?!

(GM): One poem in particular from your most recent release, black god mother this body, "testimonio," stood out to us for its use of seamless transitions from English to Spanish and vice versa. We've noticed in many of your poems you use Spanglish. It really adds a touch of authenticity to the bilingual experience. How do you decide when to use certain words/phrases in Spanish and English in "testimonio” and your other poems?

(RJL): When I think about my people, I have such pride. It’s in our music, our fervor, our connection to otherworldliness, our political engagement, our defiance, our embodied attunement to the rhythms of the world (hips that move with the grace of palm trees and waves), the portal opening of the sound of the coquí echoing in our ears perhaps even an extended measure upon measure playing in the blood. Boricua. Soy boricua and diasporican, and I have grown up listening to stories of angels and brujas, orishas and labor organizers, santos and the origins of Latin jazz. And Papi came up also in full recognition and celebration of his blackness, which was not universally understood in my family, let alone the Puerto Rican community, and it’s still not. Still, all of the cultural traditions and practices that inform who we are and who I am come through in my work. How could it not?!

(GM): One poem in particular from your most recent release, black god mother this body, "testimonio," stood out to us for its use of seamless transitions from English to Spanish and vice versa. We've noticed in many of your poems you use Spanglish. It really adds a touch of authenticity to the bilingual experience. How do you decide when to use certain words/phrases in Spanish and English in "testimonio” and your other poems?

"When I think about my people, I have such pride. It’s in our music, our fervor, our connection to otherworldliness, our political engagement, our defiance, our embodied attunement to the rhythms of the world... |

(RJL): When I was young, there were words I did not know in English. Like I didn’t know what a living room was until I was middle school age. I had more music in my voice then, too, so used to going back and forth between all the cultures that raised me up.

The poem “testimonio” is one of grief, which is as much for Kamilah Aisha Moon as it is for my own tongue. When my grandmother died, for some reason, I stopped speaking Spanish as much; I think because it was a container for loss when it used to be a container of home and grounding, command and prayer. When my children were born, I returned to speaking Spanish with them. My son, like me, had words that only existed in Spanish; sandía is one that remains, for example. Spanish is the language I reach for when English cannot hold a profundity. English has its connotations and denotations, of course - I am a scholar whose primary language of engagement is English - but Spanish vibrates on an entirely different wavelength for me. Sometimes, there are even colors, true synesthesia, with particular words in a way that, for some reason, I don’t have with English. |

(GM): Puerto Rico is the birthplace of plena music and the bomba dance style, both of which were developed primarily as forms of communication. Bomba and plena specifically have been central in many Puerto Rican protests. Your own work addresses deep themes of racial identity and the current political climate. Do you feel that your poetry, in some ways, relates to or is an homage to this culture of lyrical protest?

(RJL): It is SUCH an honor to even have my work considered alongside these traditions! I learned recently that my great-grandfather was a poet. I had already known that he was also a labor organizer in Philadelphia. My grandfather, his son, was a constant traveler who had a distinct awareness of race and racism and the fight against it. My father worked in juvenile detention and my mother was a social worker with elders, both of them engaged with social movements and community organizing. My political education and invitation to protest began early and so did their support of artistic creation. I’ve been writing since I was 8 years old and I’ve kept most of those journals, so I can see a questioning around equity in myself even in those early years of forming.

When I was writing some of the poems within black god mother this body, I was actually starting to take a plena class with my husband and baby at La Peña Cultural Center in Berkeley, one of the most established centers for bomba y plena. I wanted for my son an immersion in instrumentation, cultural sharing in the circle, and a familial engagement with the song traditions as much as I wanted to inspire my children to engage with community for our collective thriving. Goodness, my son’s first lullaby was a protest song I made up for him in Spanish! The relationship is there, and as a Diasporican I would love to learn more about bomba and plena. Maybe someday soon I’ll go back to PR for an impromptu residency and immersion with family.

(RJL): It is SUCH an honor to even have my work considered alongside these traditions! I learned recently that my great-grandfather was a poet. I had already known that he was also a labor organizer in Philadelphia. My grandfather, his son, was a constant traveler who had a distinct awareness of race and racism and the fight against it. My father worked in juvenile detention and my mother was a social worker with elders, both of them engaged with social movements and community organizing. My political education and invitation to protest began early and so did their support of artistic creation. I’ve been writing since I was 8 years old and I’ve kept most of those journals, so I can see a questioning around equity in myself even in those early years of forming.

When I was writing some of the poems within black god mother this body, I was actually starting to take a plena class with my husband and baby at La Peña Cultural Center in Berkeley, one of the most established centers for bomba y plena. I wanted for my son an immersion in instrumentation, cultural sharing in the circle, and a familial engagement with the song traditions as much as I wanted to inspire my children to engage with community for our collective thriving. Goodness, my son’s first lullaby was a protest song I made up for him in Spanish! The relationship is there, and as a Diasporican I would love to learn more about bomba and plena. Maybe someday soon I’ll go back to PR for an impromptu residency and immersion with family.

|

(GM): You are the cofounder of the Latinx literary journal, The Acentos Review, and you teach future educators at St. Mary’s College of California. How does your role at The Acentos Review influence your poetry? How does your status as a poet translate into your teaching, and how does your education influence your poetry?

(RJL): The Acentos Review comes from the work of the Acentos Bronx Poetry Showcase, which was a monthly series in the Bronx from 2003-2008. That community was an important incubator for who I am as a creative and as a community organizer within arts spaces. For nearly 15 years, The Acentos Review has been going strong, now having published over 900 Latinx voices across many languages, all online. In a year, we easily review over a thousand submissions. It’s my absolute honor to receive those invitations to partnership. Even our rejections are opportunities to nurture community! We’ve had the great fortune of being the site of debut publications, publishing youth and elders and everyone across every experience in between. |

My own work has exponentially grown because of how much I read each year. In my reading, I learn a lot, and it pushes me to try new forms, writing styles, and read differently. If someone mentions an author I haven’t read in a cover letter, I put them on my list. I try to be attentive to the craft of holding space for the writers and artists and the opportunity to grow as an artist myself. I think every creative should work in some capacity as an editor or workshop leader!

My education as an academic influences how I read and come to understand a text (whether written, musical, visual, etc.) and how I take what I understand to apply to my own creative process. My practice as an educator also influences how I approach communicating through poetry, sometimes with a focus on the concise and the direct. I think that my practice as a creative has the greatest impact on my work as an educator, though. I use metaphor as a teaching tool. I engage teachers as community organizers and as creatives. I primarily work with English educators but also with educators across other disciplines, and I’m always pushing them to invent, to engage, to create whatever it is that they want to assign to their students, to also just play for the joy of it, because joy translates in the classroom.

Creation and teaching are both energetic practices. We have to find a flow and be aware of how to build and maneuver energies in healthy ways that will see their way through shared production. We have to be aware of what will drain our energy and create boundaries so that we can do what is necessary to do—pay the bills, take the meeting, grade the paper, organize the book, channel an experience, touch a future, etc.—and also be attuned to the flow of creation. My greatest gift is becoming more aware of that attunement, a practice and awareness I attempt to share with others.

(GM): Throughout this interview, we’ve asked you plenty of questions about your identity and heritage as an Afro-Boricua woman and how it has influenced your writing in your career. Much of your work has celebrated this part of your identity, but we’d like to know if this has ever been a significant hurdle for you to overcome? How do you hope to pave the way for future poets like yourself?

(RJL): Being Afro-Boricua, my life and the lives of my people and my children are constantly under threat. I have been called all the names, had to be so many times more accomplished in my career and still had my excellence undermined and questioned. I have had my livelihood threatened, because I dared to even exist. I have been ignored, talked over, passed over, discounted, assaulted. These are the oppressive tools of whiteness.

Lucille Clifton reminds me to celebrate all the things that have tried to kill me and have failed. They failed! And so while I am breathing in the success of my survival, I am also creating paths of thriving, scripts for joyful practice, pages of “you are not alone,” and institutions of “I see you and celebrate you shining and how you get there.” What I create, I hope will be a model for those who come after me, whether rising now or many generations from now. I want to be a good ancestor to those who come. I wish them a better way, flight and groundedness and the holiness of their own delight in the collective joy of the firmament.

My education as an academic influences how I read and come to understand a text (whether written, musical, visual, etc.) and how I take what I understand to apply to my own creative process. My practice as an educator also influences how I approach communicating through poetry, sometimes with a focus on the concise and the direct. I think that my practice as a creative has the greatest impact on my work as an educator, though. I use metaphor as a teaching tool. I engage teachers as community organizers and as creatives. I primarily work with English educators but also with educators across other disciplines, and I’m always pushing them to invent, to engage, to create whatever it is that they want to assign to their students, to also just play for the joy of it, because joy translates in the classroom.

Creation and teaching are both energetic practices. We have to find a flow and be aware of how to build and maneuver energies in healthy ways that will see their way through shared production. We have to be aware of what will drain our energy and create boundaries so that we can do what is necessary to do—pay the bills, take the meeting, grade the paper, organize the book, channel an experience, touch a future, etc.—and also be attuned to the flow of creation. My greatest gift is becoming more aware of that attunement, a practice and awareness I attempt to share with others.

(GM): Throughout this interview, we’ve asked you plenty of questions about your identity and heritage as an Afro-Boricua woman and how it has influenced your writing in your career. Much of your work has celebrated this part of your identity, but we’d like to know if this has ever been a significant hurdle for you to overcome? How do you hope to pave the way for future poets like yourself?

(RJL): Being Afro-Boricua, my life and the lives of my people and my children are constantly under threat. I have been called all the names, had to be so many times more accomplished in my career and still had my excellence undermined and questioned. I have had my livelihood threatened, because I dared to even exist. I have been ignored, talked over, passed over, discounted, assaulted. These are the oppressive tools of whiteness.

Lucille Clifton reminds me to celebrate all the things that have tried to kill me and have failed. They failed! And so while I am breathing in the success of my survival, I am also creating paths of thriving, scripts for joyful practice, pages of “you are not alone,” and institutions of “I see you and celebrate you shining and how you get there.” What I create, I hope will be a model for those who come after me, whether rising now or many generations from now. I want to be a good ancestor to those who come. I wish them a better way, flight and groundedness and the holiness of their own delight in the collective joy of the firmament.