The Pain Scale

by Audrey T. Carroll

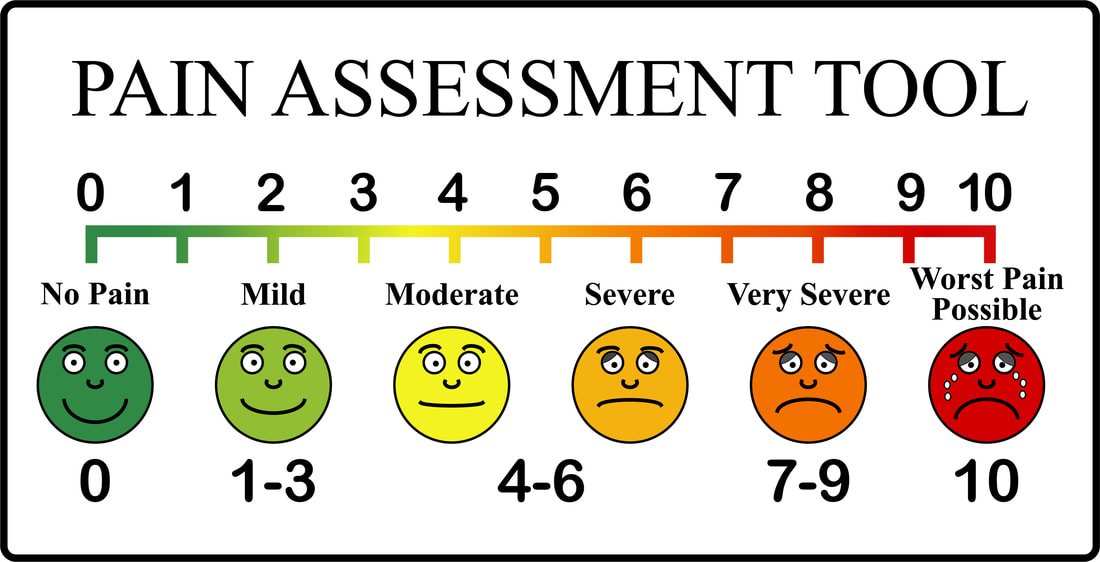

0 No Pain (No Gain)

I’ve never known if, when a doctor asks you to “rate your pain, on a scale of one to ten,” you are actually allowed to say “zero.” I’ve been too afraid to ask, because if my pain is a zero, then what the hell am I seeing a doctor for anyway? My pain is always discounted to begin with, so why would I willingly give the ammunition to ignore my body’s cries for help?

To be fair, it has been a long while since I could truthfully say “zero”—so long, in fact, that I don’t remember when, so even asking at this point would be a hypothetical waste of everyone’s time. For one thing, I’ve had pain half the time from the July before my thirteenth birthday until I was in my late-twenties (see point seven), and ever since it’s only been a matter of measuring degrees, but maybe before all of that there was a time when the days with pain stood apart from the days without.

I’ve never known if, when a doctor asks you to “rate your pain, on a scale of one to ten,” you are actually allowed to say “zero.” I’ve been too afraid to ask, because if my pain is a zero, then what the hell am I seeing a doctor for anyway? My pain is always discounted to begin with, so why would I willingly give the ammunition to ignore my body’s cries for help?

To be fair, it has been a long while since I could truthfully say “zero”—so long, in fact, that I don’t remember when, so even asking at this point would be a hypothetical waste of everyone’s time. For one thing, I’ve had pain half the time from the July before my thirteenth birthday until I was in my late-twenties (see point seven), and ever since it’s only been a matter of measuring degrees, but maybe before all of that there was a time when the days with pain stood apart from the days without.

~

1–3 Mild Pain (nagging, annoying, interfering little with activities of daily living)

AKA Why are you here?

1. It doesn’t sound so bad, does it? My foot missed the board of the scooter, and the wheels rode along the concrete sidewalk where it was broken, shooting up like a ramp in a skate park. I had been navigating this mini-hill for years, where roots must have been growing aggressively underneath care of the enormous tree that stood between the sidewalk and the road. But the scooter was new, and so was my balance on it, and so I missed my footing and

collided with the ground. (This will be a pattern, this loss of balance, though I will not think about it much for another fifteen years.)

In truth, the skinned knee hurt, but it was nothing major, no broken bones. It was a lot of blood, the sight of which made me dizzy (dizziness—another pattern to keep an eye out for), and I can still remember the hot red gushing down the front of my leg and staining the top of my white sock folded over. What I remember more than the pain, more than the blood, was the adult body blocking the front door, refusing to allow me inside to clean and bandage myself until I put the scooter away because someone might steal it. The potential harm to property outweighed the realized harm to my own child-sized body.

(Childhood and pain weave together again and again—the betrayal of blood, the lonely physicality of labor, the callous disregard for the little girl who stared up to look for help from her elders. Pain is recursive. It is not linear; it resists the confines of narrative.)

The implied confession would stay with me long after my skin knit itself back together so well that no scar remained. And the confession would become louder as the years passed, the way the “too-big” shape of the child-body is mocked into reduction, the way the body is trespassed and its pleas for help ignored, the way that threats are laid like broken glass within a windowpane, all while they insist that nothing has cracked. These same adults who do not believe will never believe, their certainty a tool to will silence, to ignore pain within and without. And this will return, too, this edict to ignore your pain, it’s in your head, talking about it just makes it worse.

2. What is the dead center of nagging and annoying? A contender: a sunburn so bad that my arms oozed clearish yellow, that we had to go to the doctor, that movement hurt enough to carve out a place in memory. It is the interferences that are the most vivid, the way a new wool uniform kilt slides over sunburnt skin which is hurting in its most basic job of existence, skin which is peeling to escape a damaged body; this pain is disbelieved, an immeasurable thing and therefore unimportant. Stop being so dramatic.

Again, before I’ve ever heard the word for it, the same group of adults gaslight my body’s reality; the lights are not dimming, you do not feel so much pain—it is only in your head, don’t

you remember?

Or perhaps: a post-surgery stitch not believed. The surgery itself was not felt, though awake. Incisions were made to remove a wisdom tooth before it took root, stopping the thing growing sideways and forcing all the others to grow sideways along with it. The after-pain transforms, moment to moment, sharp to dull to pulsing to swelling. The pain is a chameleon, no way to describe its color without the next moment proving you wrong. I wanted to obey the instincts of my body, to keep my mouth closed, to keep my tender insides protected, to prevent myself from spilling yet more of my own blood. And demands made by adults: open wide so we can see, the same people who would tell me in any other circumstance to do the exact opposite. All efforts to explain pain ignored, treated as strange fantasy, until a doctor confirms that stitch does, in fact, weave through cheek.

And once again, the same group of adults gaslight my body’s reality; the lights are not dimming, you do not feel so much pain—it is only in your head, don’t you remember? Childhood and adolescence prepare you for The Real World; I do not yet realize how few will believe my kind of body’s experiences there, either.

3. Twenty-one years with no broken bones, and then an elbow fractured just enough to spiderweb X-ray images. I was young, and so perhaps can be forgiven for the lack of insistence and vigilance that I would learn in the years to come. When the doctor said to use a sling for a week, I did; and, when he said to start moving the arm at that time, I did. During the flooding of the rivers from hurricane skies, I pushed through my pain, sure that it must be normal. I did not know yet that the same doctor had ignored an acquaintance’s complaints of pain until she was diagnosed with strep throat in urgent care. I did not trust my own body’s pain, my faith instead in a professional who didn’t so much as schedule a follow-up appointment.

In the aftermath of the break, there were the little interferences with activities of daily living: showering, styling hair, carrying books. These interferences work as a kind of foreshadowing more than anything, a glimpse of what life will be like when a cane occupies one hand and solutions must be calculated at every turn.

AKA Why are you here?

1. It doesn’t sound so bad, does it? My foot missed the board of the scooter, and the wheels rode along the concrete sidewalk where it was broken, shooting up like a ramp in a skate park. I had been navigating this mini-hill for years, where roots must have been growing aggressively underneath care of the enormous tree that stood between the sidewalk and the road. But the scooter was new, and so was my balance on it, and so I missed my footing and

collided with the ground. (This will be a pattern, this loss of balance, though I will not think about it much for another fifteen years.)

In truth, the skinned knee hurt, but it was nothing major, no broken bones. It was a lot of blood, the sight of which made me dizzy (dizziness—another pattern to keep an eye out for), and I can still remember the hot red gushing down the front of my leg and staining the top of my white sock folded over. What I remember more than the pain, more than the blood, was the adult body blocking the front door, refusing to allow me inside to clean and bandage myself until I put the scooter away because someone might steal it. The potential harm to property outweighed the realized harm to my own child-sized body.

(Childhood and pain weave together again and again—the betrayal of blood, the lonely physicality of labor, the callous disregard for the little girl who stared up to look for help from her elders. Pain is recursive. It is not linear; it resists the confines of narrative.)

The implied confession would stay with me long after my skin knit itself back together so well that no scar remained. And the confession would become louder as the years passed, the way the “too-big” shape of the child-body is mocked into reduction, the way the body is trespassed and its pleas for help ignored, the way that threats are laid like broken glass within a windowpane, all while they insist that nothing has cracked. These same adults who do not believe will never believe, their certainty a tool to will silence, to ignore pain within and without. And this will return, too, this edict to ignore your pain, it’s in your head, talking about it just makes it worse.

2. What is the dead center of nagging and annoying? A contender: a sunburn so bad that my arms oozed clearish yellow, that we had to go to the doctor, that movement hurt enough to carve out a place in memory. It is the interferences that are the most vivid, the way a new wool uniform kilt slides over sunburnt skin which is hurting in its most basic job of existence, skin which is peeling to escape a damaged body; this pain is disbelieved, an immeasurable thing and therefore unimportant. Stop being so dramatic.

Again, before I’ve ever heard the word for it, the same group of adults gaslight my body’s reality; the lights are not dimming, you do not feel so much pain—it is only in your head, don’t

you remember?

Or perhaps: a post-surgery stitch not believed. The surgery itself was not felt, though awake. Incisions were made to remove a wisdom tooth before it took root, stopping the thing growing sideways and forcing all the others to grow sideways along with it. The after-pain transforms, moment to moment, sharp to dull to pulsing to swelling. The pain is a chameleon, no way to describe its color without the next moment proving you wrong. I wanted to obey the instincts of my body, to keep my mouth closed, to keep my tender insides protected, to prevent myself from spilling yet more of my own blood. And demands made by adults: open wide so we can see, the same people who would tell me in any other circumstance to do the exact opposite. All efforts to explain pain ignored, treated as strange fantasy, until a doctor confirms that stitch does, in fact, weave through cheek.

And once again, the same group of adults gaslight my body’s reality; the lights are not dimming, you do not feel so much pain—it is only in your head, don’t you remember? Childhood and adolescence prepare you for The Real World; I do not yet realize how few will believe my kind of body’s experiences there, either.

3. Twenty-one years with no broken bones, and then an elbow fractured just enough to spiderweb X-ray images. I was young, and so perhaps can be forgiven for the lack of insistence and vigilance that I would learn in the years to come. When the doctor said to use a sling for a week, I did; and, when he said to start moving the arm at that time, I did. During the flooding of the rivers from hurricane skies, I pushed through my pain, sure that it must be normal. I did not know yet that the same doctor had ignored an acquaintance’s complaints of pain until she was diagnosed with strep throat in urgent care. I did not trust my own body’s pain, my faith instead in a professional who didn’t so much as schedule a follow-up appointment.

In the aftermath of the break, there were the little interferences with activities of daily living: showering, styling hair, carrying books. These interferences work as a kind of foreshadowing more than anything, a glimpse of what life will be like when a cane occupies one hand and solutions must be calculated at every turn.

~

4–6 Moderate Pain (interferes significantly with activities of daily living)

AKA Find the measurable evidence.

AKA Can you get off the couch if it’s not an emergency?

4. The rumor was that adults can’t get hand, foot, and mouth disease. This, as it turns out, is a lie. The pain was middling: if I absolutely had to, I could get off the couch, though it hurt the bottoms of my feet every time as though the skin had peeled and regrown and was still tender. I couldn’t walk without pain—not stabbing, not searing, but still present in every step, like a toned-down version of the original Little Mermaid tale. This was not the version of my childhood nostalgia. I never really thought about the distress of losing one’s voice in any version of the story—a voice lost not by stitches sewn or authoritative glares, but by choice.

The itching of the disease was bothersome, of course. The red spots and weak nails were the only measurable factors. The worst of it, though, was the way that I could feel the skin in my throat peeling, could feel the damage of each individual sore. I couldn’t drink water or eat without pain; even letting my throat naturally constrict the way that it must’ve done hundreds of times every day before only served as a constant reminder that I was sick. (This was still in the time when my body had to remind me it was sick; after a certain threshold, other people help you remember, too.)

5. This is the threshold for the COVID vaccine. I had read the warnings for weeks about the vaccine on Twitter from those with fibromyalgia and other varieties of chronic pain. These reports were criticized as scaring people away from getting vaccinated; I suppose I put aside thoughts about the way that people fear one day of the kind of pain that I live with regularly. And then others—many able-bodied, perhaps—countered with their mostly asymptomatic stories of It’s not so bad, look, it was only a sore arm for a few hours, oh I was just tired, no worse than a mild flu for a day, the assurances to the unvaccinated drowning out the forewarnings to the ill and disabled. It is not common knowledge, perhaps, that the ill and disabled know what to do with rationed time and energy, and clarified expectations are a miracle of knowledge in that process. But the culture downplays (disbelieves) (disregards) disabled bodies and

experiences (ill bodies and experiences) (female/femme/female-coded bodies and experiences). The shaming of those who shared less-than-pleasant experiences became a deluge of persistent positivity.

I was prepared for the first vaccine to cause a flare, but I hadn’t realized just how much it would be a trip down memory lane to my pre-medicated, pre-diagnosis fibromyalgia: pain all over (especially in my trigger points), memory issues, problems doing simple physical tasks, feeling dazed and exhausted. With the second vaccine dose came even more pain, sleepless nights, a back that could find no comfort. Dose two also came with chest pain, a tightness like either a heart attack or, I eventually realized, hyper-localized labor pains. And the booster brought with it fever, full-body sweats, intense pain in both arms, and a deep aversion to leaving the couch.

It was impossible to imagine how the pain rated separate from fibromyalgia, almost as impossible as it was to imagine how bad these experiences would be if my body was still undiagnosed or untreated, if it was this bad with the Gabapentin.

(This is the trouble with the pain scale: how does someone with chronic pain rate anything? Do you account for your baseline? Do you rate based on whatever is considered “normal”—i.e. there should be no pain at all? We can’t really share pain. It is a lonely and singular experience, even if you are with someone who might also understand it from their own experiences. And even when we try to share our pain, how often is it not believed or not understood for any number of reasons? You’re just anxious. You’re just depressed. You just need to drink more water. You just… you just… you just…)

I used ibuprofen like I had used with undiagnosed fibro, a heating pad that I had gotten for the unbearable pain when my endometriosis was out of control, and ice everywhere that I reasonably could. This, too, is one of the lessons of a chronic pain condition: so often, you are on your own; so often, you must design your own solutions, engineer your own comfort, because it is so infrequent that someone else will help you manage. This was a lesson that I learned early, well before any symptom of chronic pain bubbled to the surface.

6. Contractions weren’t the first sign that I was in labor. I had woken up at 11:30 at night, my body telling me to stay awake while remaining coy as to the matter of why, and then my water broke in bed and the entire way into the bathroom. It wasn’t until after I had been tested at the hospital, confirmed to be in labor, and in my designated birthing bed, that the contractions started. I was told to get some rest, but that was impossible. I was very clear from the get-go: I wanted the best drugs that insurance could buy. I was informed that the anesthesiologist didn’t get in until 9:00 a.m. and I would have to wait. (I don’t know if he was actually a half hour late to my room or if that’s the memory warping of pain talking.)

It was like some of the worst cramps of my life—migraines are to headaches as contractions are to (even endometrial) cramps. The pain would compress in my uterus and then shoot intense signals all around my torso. I was in tears; it was difficult to even breathe. I don’t think I could have gotten out of bed in an emergency, and it would have been more merciful if the pain would’ve knocked me out. It was approaching mind-altering pain territory, with slight hints of my brain sending warnings that I was dying. I was no stranger to the feeling of my body betraying me; it had been two years since being diagnosed with fibromyalgia, a condition where everything is processed as a threat and reacted to accordingly. Perhaps the body’s self-betrayal is yet another threshold of this level of pain.

This will not be the last time that pregnancy makes an appearance on this pain scale.

AKA Find the measurable evidence.

AKA Can you get off the couch if it’s not an emergency?

4. The rumor was that adults can’t get hand, foot, and mouth disease. This, as it turns out, is a lie. The pain was middling: if I absolutely had to, I could get off the couch, though it hurt the bottoms of my feet every time as though the skin had peeled and regrown and was still tender. I couldn’t walk without pain—not stabbing, not searing, but still present in every step, like a toned-down version of the original Little Mermaid tale. This was not the version of my childhood nostalgia. I never really thought about the distress of losing one’s voice in any version of the story—a voice lost not by stitches sewn or authoritative glares, but by choice.

The itching of the disease was bothersome, of course. The red spots and weak nails were the only measurable factors. The worst of it, though, was the way that I could feel the skin in my throat peeling, could feel the damage of each individual sore. I couldn’t drink water or eat without pain; even letting my throat naturally constrict the way that it must’ve done hundreds of times every day before only served as a constant reminder that I was sick. (This was still in the time when my body had to remind me it was sick; after a certain threshold, other people help you remember, too.)

5. This is the threshold for the COVID vaccine. I had read the warnings for weeks about the vaccine on Twitter from those with fibromyalgia and other varieties of chronic pain. These reports were criticized as scaring people away from getting vaccinated; I suppose I put aside thoughts about the way that people fear one day of the kind of pain that I live with regularly. And then others—many able-bodied, perhaps—countered with their mostly asymptomatic stories of It’s not so bad, look, it was only a sore arm for a few hours, oh I was just tired, no worse than a mild flu for a day, the assurances to the unvaccinated drowning out the forewarnings to the ill and disabled. It is not common knowledge, perhaps, that the ill and disabled know what to do with rationed time and energy, and clarified expectations are a miracle of knowledge in that process. But the culture downplays (disbelieves) (disregards) disabled bodies and

experiences (ill bodies and experiences) (female/femme/female-coded bodies and experiences). The shaming of those who shared less-than-pleasant experiences became a deluge of persistent positivity.

I was prepared for the first vaccine to cause a flare, but I hadn’t realized just how much it would be a trip down memory lane to my pre-medicated, pre-diagnosis fibromyalgia: pain all over (especially in my trigger points), memory issues, problems doing simple physical tasks, feeling dazed and exhausted. With the second vaccine dose came even more pain, sleepless nights, a back that could find no comfort. Dose two also came with chest pain, a tightness like either a heart attack or, I eventually realized, hyper-localized labor pains. And the booster brought with it fever, full-body sweats, intense pain in both arms, and a deep aversion to leaving the couch.

It was impossible to imagine how the pain rated separate from fibromyalgia, almost as impossible as it was to imagine how bad these experiences would be if my body was still undiagnosed or untreated, if it was this bad with the Gabapentin.

(This is the trouble with the pain scale: how does someone with chronic pain rate anything? Do you account for your baseline? Do you rate based on whatever is considered “normal”—i.e. there should be no pain at all? We can’t really share pain. It is a lonely and singular experience, even if you are with someone who might also understand it from their own experiences. And even when we try to share our pain, how often is it not believed or not understood for any number of reasons? You’re just anxious. You’re just depressed. You just need to drink more water. You just… you just… you just…)

I used ibuprofen like I had used with undiagnosed fibro, a heating pad that I had gotten for the unbearable pain when my endometriosis was out of control, and ice everywhere that I reasonably could. This, too, is one of the lessons of a chronic pain condition: so often, you are on your own; so often, you must design your own solutions, engineer your own comfort, because it is so infrequent that someone else will help you manage. This was a lesson that I learned early, well before any symptom of chronic pain bubbled to the surface.

6. Contractions weren’t the first sign that I was in labor. I had woken up at 11:30 at night, my body telling me to stay awake while remaining coy as to the matter of why, and then my water broke in bed and the entire way into the bathroom. It wasn’t until after I had been tested at the hospital, confirmed to be in labor, and in my designated birthing bed, that the contractions started. I was told to get some rest, but that was impossible. I was very clear from the get-go: I wanted the best drugs that insurance could buy. I was informed that the anesthesiologist didn’t get in until 9:00 a.m. and I would have to wait. (I don’t know if he was actually a half hour late to my room or if that’s the memory warping of pain talking.)

It was like some of the worst cramps of my life—migraines are to headaches as contractions are to (even endometrial) cramps. The pain would compress in my uterus and then shoot intense signals all around my torso. I was in tears; it was difficult to even breathe. I don’t think I could have gotten out of bed in an emergency, and it would have been more merciful if the pain would’ve knocked me out. It was approaching mind-altering pain territory, with slight hints of my brain sending warnings that I was dying. I was no stranger to the feeling of my body betraying me; it had been two years since being diagnosed with fibromyalgia, a condition where everything is processed as a threat and reacted to accordingly. Perhaps the body’s self-betrayal is yet another threshold of this level of pain.

This will not be the last time that pregnancy makes an appearance on this pain scale.

~

Photo by Yuris Alhumaydy on Unsplash

7–10 Severe Pain (disabling; unable to perform activities of daily living)

AKA The ratings where doctors stop believing you.

7. This is the nexus of “your pain is normal” and “you can’t be in this level of pain.” The “fifth vital sign” can be pain. Other times, the fifth vital sign is the menstrual cycle. The four standard vital signs are body temperature, heart rate/pulse, respiratory rate, and blood pressure. The process of expressing “menstrual troubles” (i.e. undiagnosed and untreated endometriosis) to doctors often goes something like this, whether explicitly or implied: Being in severe pain for half of the month (translation: half of your life for all the years that you could potentially give birth) is normal and natural; using double the feminine hygiene products that you should be is normal and natural; full body pain is normal and natural; only experiencing relief for two weeks out of the month is normal and natural. Just try harder to perform the activities of daily living. Cut back on the caffeine that allows you to concentrate at work; exercise more with a disabled body prone to chronic pain; take some ibuprofen and it’ll be fine.

It took endometriosis getting exponentially worse post-pregnancy and a doctor who believed me to get treated; I imagine there are lots of women unlucky enough to have the former and then even more unlucky in their lack of the latter. Alleviating pain seems like something scientific and sure and medical; it should not come down to something so fickle and intangible as luck, and yet--

Note: Could also be interchanged with number eight. The shades of pain are difficult to parse.

8. There is no standard “sixth vital sign,” but gait is something that can stand in for it. This is the threshold of “Can I shower independently?” and the answer is no. Untreated and undiagnosed fibromyalgia symptoms may include: medical professionals who don’t believe you until you come in with a cane; dizziness; pain; a neck that feels constantly on fire; inability to think; inability to concentrate; inability to remember; and, yes, inability to shower independently. This is not a pain that can be countered with whatever you might pick up in the supplements aisle at CVS, and it can get worse the longer you’re unable to convince a doctor to believe you.

(This process of manifesting belief is in part dependent upon your ability to perform a persuasive essay, but in even larger part dependent upon a medical professional taking you seriously.)

There are no signs that they can measure, at least not traditionally: your blood work will show nothing; your CT scan and your MRI will show nothing; the billion-and-a-half pregnancy tests that they make you take will show nothing. The root of the controversy in the medical community regarding fibromyalgia is the disbelief toward self-reporting, the trouble of getting people to believe pain at all, nonetheless a particular severity of pain.

The designated medical professional must prod you in pre-determined places—“trigger points” when I was diagnosed, though I’ve seen them called “tender points” now. Maybe “tender points” are less violent, maybe it’s a phrase meant to encourage the idea of tenderness in chronic pain. Or maybe there’s some random medical reason for the swap, because I find it difficult to believe that fibromyalgia has someone working PR to make it sound less threatening than its long and complicated-sounding name might suggest. Whatever you call them, these points are both: the places where pain radiates are triggers—they are violent—but they are also tender—they have violence enacted upon them. It is a survival instinct, a coping mechanism, fibromyalgia, but it is also and always a body turning anticipation into violence against itself.

9. Pain is not linear; it is recursive. The same event can have separate moments in separate rankings on the pain scale, just as completely unrelated pains can take up the same intensity on the scale. In truth, I have never told a doctor that my pain level is at a nine, not that I can recall. I don’t know if I would even be believed if I did make this claim aloud; I’ve been disbelieved enough times that I never bank on anyone else’s trust in my reports on my own body. But the twenty or so minutes where I had to resist pushing during labor, though my daughter and my body both protested, likely belongs here. It was a difference of a half a centimeter of dilation between me and freedom, between my daughter and freedom, and I couldn’t even measure that amount between my fingers.

(Expressing the intensity of labor pain is cliché, so talked about as a marker of extremity that it is often disregarded as overwrought and melodramatic. Overwhelmingly this dismissal is made by those who haven’t experienced it for themselves. The perspective of the one who experiences the pain is not taken as truth. What is truth when it comes to pain? Why is it so often allowed to be defined by those outside of pain?)

This is my “Could I get out if there was a fire?” level. The answer is a resounding no. The world could burn around me in those minutes, and I’m not sure that I could have even been able to bring myself to care.

10. Literally blinding pain.

One missed painkiller in the bleary sleep-deprived fog of postpartum life. As I returned to bed—from the bathroom? From feeding the baby? I can’t quite be sure—I felt a pang so strong in my core that I literally fell over. After so long a time spent with dizziness, I managed to artfully collapse against the side of the bed, still half-standing. I do not know if it was being vertical that left me first, or my vision, but for however long it took, I stayed in place, in a state of near-unconsciousness, simply feeling the afterwaves of the most painful seconds I’ve ever experienced, a pain that somehow surpassed even the literal acts of labor itself. (I suppose this is not a true mystery: one experience had an epidural that could be delivered by a button’s press, the other did not.) There was no doctor to report this level ten pain to, of course, in the dark of night in my own bedroom.

My worst moment of pain was literally experienced alone. There were others nearby, but no one conscious, no witnesses to even contradict it. No matter the number assigned, often arbitrarily, to the experience of pain, there are two constants: the people who will not believe you, and the aloneness, always, of the hurt itself. No matter the pain that comes next to unseat this one and that, the constants will always be there, fixed stars blinking back in the dark.

AKA The ratings where doctors stop believing you.

7. This is the nexus of “your pain is normal” and “you can’t be in this level of pain.” The “fifth vital sign” can be pain. Other times, the fifth vital sign is the menstrual cycle. The four standard vital signs are body temperature, heart rate/pulse, respiratory rate, and blood pressure. The process of expressing “menstrual troubles” (i.e. undiagnosed and untreated endometriosis) to doctors often goes something like this, whether explicitly or implied: Being in severe pain for half of the month (translation: half of your life for all the years that you could potentially give birth) is normal and natural; using double the feminine hygiene products that you should be is normal and natural; full body pain is normal and natural; only experiencing relief for two weeks out of the month is normal and natural. Just try harder to perform the activities of daily living. Cut back on the caffeine that allows you to concentrate at work; exercise more with a disabled body prone to chronic pain; take some ibuprofen and it’ll be fine.

It took endometriosis getting exponentially worse post-pregnancy and a doctor who believed me to get treated; I imagine there are lots of women unlucky enough to have the former and then even more unlucky in their lack of the latter. Alleviating pain seems like something scientific and sure and medical; it should not come down to something so fickle and intangible as luck, and yet--

Note: Could also be interchanged with number eight. The shades of pain are difficult to parse.

8. There is no standard “sixth vital sign,” but gait is something that can stand in for it. This is the threshold of “Can I shower independently?” and the answer is no. Untreated and undiagnosed fibromyalgia symptoms may include: medical professionals who don’t believe you until you come in with a cane; dizziness; pain; a neck that feels constantly on fire; inability to think; inability to concentrate; inability to remember; and, yes, inability to shower independently. This is not a pain that can be countered with whatever you might pick up in the supplements aisle at CVS, and it can get worse the longer you’re unable to convince a doctor to believe you.

(This process of manifesting belief is in part dependent upon your ability to perform a persuasive essay, but in even larger part dependent upon a medical professional taking you seriously.)

There are no signs that they can measure, at least not traditionally: your blood work will show nothing; your CT scan and your MRI will show nothing; the billion-and-a-half pregnancy tests that they make you take will show nothing. The root of the controversy in the medical community regarding fibromyalgia is the disbelief toward self-reporting, the trouble of getting people to believe pain at all, nonetheless a particular severity of pain.

The designated medical professional must prod you in pre-determined places—“trigger points” when I was diagnosed, though I’ve seen them called “tender points” now. Maybe “tender points” are less violent, maybe it’s a phrase meant to encourage the idea of tenderness in chronic pain. Or maybe there’s some random medical reason for the swap, because I find it difficult to believe that fibromyalgia has someone working PR to make it sound less threatening than its long and complicated-sounding name might suggest. Whatever you call them, these points are both: the places where pain radiates are triggers—they are violent—but they are also tender—they have violence enacted upon them. It is a survival instinct, a coping mechanism, fibromyalgia, but it is also and always a body turning anticipation into violence against itself.

9. Pain is not linear; it is recursive. The same event can have separate moments in separate rankings on the pain scale, just as completely unrelated pains can take up the same intensity on the scale. In truth, I have never told a doctor that my pain level is at a nine, not that I can recall. I don’t know if I would even be believed if I did make this claim aloud; I’ve been disbelieved enough times that I never bank on anyone else’s trust in my reports on my own body. But the twenty or so minutes where I had to resist pushing during labor, though my daughter and my body both protested, likely belongs here. It was a difference of a half a centimeter of dilation between me and freedom, between my daughter and freedom, and I couldn’t even measure that amount between my fingers.

(Expressing the intensity of labor pain is cliché, so talked about as a marker of extremity that it is often disregarded as overwrought and melodramatic. Overwhelmingly this dismissal is made by those who haven’t experienced it for themselves. The perspective of the one who experiences the pain is not taken as truth. What is truth when it comes to pain? Why is it so often allowed to be defined by those outside of pain?)

This is my “Could I get out if there was a fire?” level. The answer is a resounding no. The world could burn around me in those minutes, and I’m not sure that I could have even been able to bring myself to care.

10. Literally blinding pain.

One missed painkiller in the bleary sleep-deprived fog of postpartum life. As I returned to bed—from the bathroom? From feeding the baby? I can’t quite be sure—I felt a pang so strong in my core that I literally fell over. After so long a time spent with dizziness, I managed to artfully collapse against the side of the bed, still half-standing. I do not know if it was being vertical that left me first, or my vision, but for however long it took, I stayed in place, in a state of near-unconsciousness, simply feeling the afterwaves of the most painful seconds I’ve ever experienced, a pain that somehow surpassed even the literal acts of labor itself. (I suppose this is not a true mystery: one experience had an epidural that could be delivered by a button’s press, the other did not.) There was no doctor to report this level ten pain to, of course, in the dark of night in my own bedroom.

My worst moment of pain was literally experienced alone. There were others nearby, but no one conscious, no witnesses to even contradict it. No matter the number assigned, often arbitrarily, to the experience of pain, there are two constants: the people who will not believe you, and the aloneness, always, of the hurt itself. No matter the pain that comes next to unseat this one and that, the constants will always be there, fixed stars blinking back in the dark.

Audrey T. Carroll is the author of What Blooms in the Dark (ELJ Editions, 2024) and Parts of Speech: A Disabled Dictionary (Alien Buddha Press, 2023). Her writing has appeared in Lost Balloon, CRAFT, JMWW, Bending Genres, and others. She is a bi/queer/genderqueer and disabled/chronically ill writer. She serves as a Diversity and Inclusion Editor for the Journal of Creative Writing Studies, and as a Fiction Editor for Chaotic Merge Magazine. She can be found at: AudreyTCarrollWrites.weebly.com and @AudreyTCarroll on Twitter and Instagram.

A 2024 Pushcart Prize nominee, Audrey's essay can be found in Issue 27 of Glassworks.

A 2024 Pushcart Prize nominee, Audrey's essay can be found in Issue 27 of Glassworks.