Threads

by Jeffrey S. Markovitz

Our mortality is a wound not yet seen.

-Evelyn Emma

When my mother died, I stared at her library for a long time, taking out books at random, leaving gaps of slender knowledge, and refiling them as succinctly as they were first positioned. Her bookshelves at oddly inconsistent heights, positioned as precariously as skyscrapers, held fortitudes of knowledge: a lifetime read, dog-eared, margin-noted. Highlighted passages and the passage of her life—perhaps I, a highlight—all that remained of her. I wondered if she wondered what would happen to all of her books when she was gone; if someone would select them, inherit them, cherish them as she had—their multi-colored goodness evidenced by the care and wear. Probably, I thought—not cruelly—they would be donated. By me, of course. A thrift store, for poor browsers to find her words on accident, scrawled into the off-white margins left for fresh ink to bond.

It saddened me that I wasn’t reader enough to keep them.

But before I could part with them (the only things my left-thinking mother could hoard like a modern-day materialist) I withdrew a particular volume in French I did not know. It was entitled Aucun de nous ne reviendra, by a woman of whom I had never heard (pictured, presumably it was her, on the cover) but here, amongst the other texts in various languages, she reminded me of my mother. She didn’t look like her, but the way she hoisted her chin, a pressed cigarette waiting between two fingers…that was my mother. And in the way that moments such as that can succeed to all the moments that will have to be, I realized I would never see her again, and it nearly killed me.

She would have shaken her head at such melodrama.

Flittering through the pages, as I did just to feel their wind, they stopped on their own accord (as books do when they are so marked) by a small, once-folded piece of paper. It was newsprint, the typical age-yellow of the paper clinging to the pages of the book that held it, like a decades-served prisoner so comforted by his cell that freedom is his only fear. The saved page had two highlighted lines: Essayez de regarder. Essayez pour voir. I tried to look for a French-to-English dictionary to see what they meant, but failed, and so pulled the newsprint from the armpit of the spine and unfolded it. It was from 1944 and it was in German. A German text interloping in French print: a 1944 pun at which my mother must have smirked when she placed it. She, of course, being German, could read what was there; I, her shameful American daughter whose childhood was spent pretending away my diversity in sacrifice to the gods of assimilation, knew only a passable bit.

It was a small article, one that didn’t even warrant a picture; a deeply buried (surely) story about a German war plane that had crashed. I stood there, the book in one hand and the loose sheet of paper in the other, wondering how much the propaganda machine ate holes in the story; truthfully, I was shocked it was even printed. It didn’t seem the Reich-way to publicize any—even if small—military defeat; but there it was, black on yellow for the world to see. A crashed German plane. I read crashed, not downed. Apparently, this was a mechanical, rather than Allied, tumbling.

So there it was: my mother’s war relic.

At most it was a cultural artifact from WWII. At least, my mother’s eccentricity. But her only daughter, left as I was with a bundle of paper, held it between finger pad and opposing thumb with such force as to pulverize the print into the dust that she was, that we’d all be, that she almost was: then.

She wasn’t a survivor; that was the name they gave her, afterwards. She was my mother, that fateful, accidental thing between us—a shared body, for a time—that keeps us, through death, through abomination, together. But what I’m afraid of is that I’ll forget her, her face, the way I have my beloved family dog; who I pined for, then cried for, and swore I’d never forget; now just a ripple of audible yawns and the sweet stink of dog breath my fallible memory tries to reconsider. I’m afraid I’ll forget my mother the same way, the way you write a name in sand though the spiteful moon sends waves to melt it away. So I do all I can to collect memories in consideration of nostalgia, worried about a deathbed with nothing to think back on. And the books’ pages go whif.

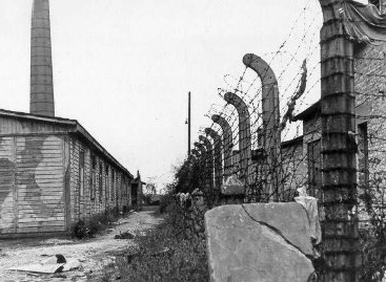

If the walls of the Altenburg factory were invisible, you’d be able to trace the smokestacks down to cauldrons. Those spires of industry, announcing civilization from the horizon to distant travelers, led through the roof and down to furnaces that were always angry, and I was the educated woman who kept them growling. Or perhaps not. Perhaps any true utility of mine was just a futile rouse, in the existential sense. Maybe, like everyone, I over-underscored my purpose; maybe I counted too many paces to a place, and forgot all about the steps behind. Maybe, I don’t know.

Maybe I was just like the screws that went by.

The factory was an amazing thing. No matter how many days went by, no matter the bizarre looks I received from my comrades, whose eyes were perpetually down, I gazed out. The conveyors that wound along as if dislodged from a tight-wound ball of string, the steam stampers (my name for them), the cauldrons. The walls with no windows. These things, functioning together, taking an inserted material and producing a valuable component: a thing; something useful. Of course I dreaded its use, whatever it was that we were producing at the factory; but I marveled at the ability of construction. The utility of creation. It made me think of motherhood, though I was sure I would never bear a child, no matter how sure I was—that deeply internal holler (like a voice saying, “You will. You will. You will.”)—when I was a little girl. I was an older girl then, and as proof that my squandered potential motherhood had suffocated that internal voice, I was rapt by the gears of the production.

Jesus said, “Forgive them Father, for they know not what they do”; and neither did we. We knew not what we created. Gun muzzles tempted their vicious innards inches from our backs, and so we fed the cauldrons, we stamped the steam, we sorted the screws. (This last thing, my job.) And I was ironic enough to quote Jesus.

Every day for months (I didn’t have the advantage of chalk to hash out, in marks, the days of my imprisonment—how taken for granted they were by my teachers, as they scrawled the chalk to nubs with arithmetic and Latin. I loved, oh how I loved, to read), every day I’d been marched there, the miles to Altenburg, to sort screws on that conveyor. The muzzles behind, buzzing with the audacity of trigger fingers. How audacious the very thought of being human is: such small things with such big designs. And my sorting screws was no more menial than running a country. An army. Than ignoring what was happening in Europe. No, my sorting screws was no more tedious than thinking, even for a second, that being a human is something special.

Some of the screws were as large as my hand (which, wasn’t very large) and some were as small as the pads of my fingertips (which, were quite small) and I had to sort them, as they glided by on treads, roller controlled underneath, into bins according to their size.

Every once in a while, I slipped one of the largest into my apron pocket. I believed (I had to believe, with God so elusive, in something) that the largest were the most important. Because I was an animal, because of gravity, I had to believe the biggest things were the most important. Screws. Men.

I never received a tattooed number. That was lore. That was only in some camps. It meant you were a laborer; so what all the following generations would scoff at was a sign of survival to those who bore them. Tattoos meant you were to be counted, and that counting was a subtle, profane indication of life somehow valuable. They were not used in my camp. My forearms were clean of ink, of blood, so I didn’t have the reassurance of survival. (I know how much it must pain people living today to read that, but I think it is time for those people to start listening to us and not to history. History has never been honest; it is like blank forearm skin, available for anyone to cut and store ink, while I was there. So I know. History is bitter medicine, but it is worse when it is filtered through human imagination.)

There are too many stereotypes to account for, these so many years later. It’s the negative sublime, the thing you stare at and cannot describe because it is a palette the colors of our brains cannot use to paint. It is experiencing the white light of the divine, and pondering why it so seldom shines. Why miracles only happen in the Torah.

How does one beautifully describe emptiness? Silence? These words are near useless.

The endless elementary schools, the endless beautiful young children with their hopeful schoolteachers, asking questions though only half-interested—perked up to not be rude, and I, expected to warm them with a smile, an anecdote, a cheerfully foreign accent. Would it pain them to know the traces of langue étrangère they heard in my voice were German? Sometimes the schoolteachers bake yellow-star cookies with Jude in black icing on them, which are eaten ravenously by the children.

According the Nuremburg Laws, I was a “Mischling of the first degree,” which were, “Persons descendent from two Jewish grandparents but not belonging to the Jewish religion and not married to a Jewish person on Sept. 15, 1935.” This bought me time; this and that I inherited the luckier traits of my two other grandparents, leaving me all sand-blond hair and sea-blue eyes; that and of course the fact that I’d never stepped foot in a synagogue. But those things only saved me for so long.

Once, back in the Altenburg factory, a comrade saw me put one of the large screws into my apron pocket and exclaimed, “Do not do that; you will be killed.”

To which I responded, “I am dead already.”

But the muzzle never nuzzled my nape, or my back, or my head, for that matter. Perhaps they never saw. Or perhaps the soldiers were just as bored as they looked. Most of them were beautiful children with misguided schoolteachers, too. I was efficient enough to sort with my non-dominant hand, so no one seemed to pay much attention to the other hand, buried deep into the pocket, with the screw.

Infrequently but steadily, I snuck my hand into the pocket, which also contained a nail file, and clumsily brushed the abrasive grain (my father’s three-hour beard stubble!) against the shaft of the screw. Over time—this was all we had: a surplus, a deluge—I learned to file with delicacy, drawing the file back and forth with only the tips of my fingers (second knuckle and above) so that the sinews of my forearm didn’t flex or undulate. Eventually, I could wear down the threads of the screw’s shaft to near nothing, smoothing flat what was designed to grip, before withdrawing the screw, placing it in its bin, and beginning again with another.

When I arrived at the camp near Altenburg from Dresden, they found the file in my pocket (this had been a different pocket; I had been stripped of my previous clothes, made to stand naked long enough to be humiliated, before being given new rags), as they found all of the things in the world that had belonged to me. They took everything, but the file. This they let me keep, out of mockery, to laugh at the absurdity that, despite my haggard condition, I could do something as superficial as shape my nails. As my teeth rotted, as my hair thinned, as my muscles betrayed the bone underneath, as my tongue became sandpapered like the blade of the file itself; they’d frequently ask to see my nails—the round clean shape of them, the kept cuticle, the finish of an ocean-loved shell. They’d call to me during marches, “Show us the nails,” and I would raise my hands—surrender and spectacle—for them to examine. And their yellowed laughter would seem to catch the sky, echo as if we were all cloistered somewhere. The sound of it triumphant as church bells, psychotic as air-raid sirens, alluring as isle-stayed Sirens, noxious like a snake’s kiss. They never worried I’d stab someone: them, myself. The joy of the anachronism blunted their boredom and I had fine nails until they began to break. Eventually, they forgot all about it, and so I had the file, and the screws.

I didn’t know what good filing the screws would do; I just had to have purpose, some rationality. I had to have something that was mine, just a little agency I could call upon that was geared toward the future. Even if it was a carrot on a string, even if it was so close to nothing that I could laugh at myself for even thinking of it (laughter, even in self-hatred, was balm). It was breath while I was submerged, and so I filed clean the threads of a screw or two a day, no more superficial an action as any other we demand our simple bodies to do. But, of course, the screws had to go to something. We all knew what the bellowing factory was a part of, even if we didn’t see the direct result, and it was a human thing for me to do, to hold out hope that my extended toe into the aisle might cause one of them to trip.

I wondered, flightily, as girls did, what people would think and how they would remember all of it. I knew it would end, eventually. How like everything. But posterity—what would it think of this final conclusion: the realization that despite our millennia of egotistical arrogance in thinking we were the champions of the Earth, that we were truly tiered at some class far below the animals. A hundred years hence, when the necessary reality ceded to the eventual mythology, how would the writers appropriate what that was for prose? They would have to, of course; the sound waves from our mutable voices would only travel so far; but how would the new voices sound? How would they carry the legacy of this suffering? Could a poem ever be properly impregnated with the dissonant fugue of such rancid melodies? I feared the noblest of future scribes would only be able to get this as a myth, a Trojan Horse, a golden-threaded labyrinth, the words of the Torah flying away from the fire of their own burning pages; but perhaps that is all the past is: a broken circle beyond which the voices of sufferers tremble out into nothing.

A recent evening, I had a nightmare. I was on an interstate, heading from somewhere to somewhere, but there wasn’t a single exit offering reprieve from the infinite stretch. All that existed was flat road—long grey expanse bisected by yellow paint and flanked by high concrete dividers. No shoulder, no green signs marking the impending escape routes. It moved on forever, road to horizon like the prize-winning photographs of the American desert, but I was horrified. The interstate in its grandiosity, linking one side of the country to the other, zagging like a heartbeat blip across the landscape: north/south plummets and hikes with marginal east/west progress. My rational mind would know that ocean was inevitable, but my dreaming mind interpreted Eisenhower’s web as suburban murder. It was all going and no stopping, all destination and no journey. How horrible it was to go on forever and never get off. How horrible to see all the things one could experience just beyond the shoulders, but be caught in a racing thing only interested in forward so that all those roadside attractions became blurs of the stuff memory lusts for, but like in dreams, are gone the more one tries to remember them after waking. It’s because of words; it’s because we try to use words to describe dreams, and they are not the things of words. They are beyond words. Dreams and nightmares both.

I remember when my mother first told me of the screws.

We were on a trip to Philadelphia, a city she loved; it was the first place she lived in America and I always thought this brought her some kind of affection for the place I thought was rather dirty. She wanted to walk me around her old neighborhood, a place she painstakingly plotted out on maps but had trouble, on the ground, locating. We wandered, presuming which direction to go (her head shaking negative at how quickly, how much, things changed) until we eventually just decided that where we were was in fact the neighborhood in which she once lived. It was a simple self-deception, the ruse of it just a platform of nostalgia; and for her, it worked. She gleamed with pride at the concrete of the sidewalks upon which she may or may not have ever walked. I was less astonished, the evidence of this in my face or in the small action of my kicking away a piece of trash rather than stepping over it. To all of this, she replied, “What is the greater talent, loving Paris? A place everyone knows to love? Or loving Philly, a place you have to work to love? Isn’t there a greater talent in loving something that isn’t so obvious? Expectations are really just a matter of consensus.”

“Beauty is Truth,” I said, quoting a literature class, of which I was then in the throes. I was a college student then, and pretention was no less an exercise of common course than waking to resume breathing—having forgotten that one breathes all through sleep.

“Beauty is no such thing,” she said, becoming serious. “Truth—who’s truth? Beauty is most in what is false, what isn’t obvious.”

She told me about the filing of the screw threads in a café toward the center of the city, where we sat as two women with independent drinks and a shared cheese Danish. She explained the nail file, the clandestine wearing-away of a screw-or-two-a-day in opposition of some phantasm. She told that story with a sense of pride that I could not understand; I could not see the heroism, the valiance she purported to own in this small act of courage. I was, generally—as most people were and should have been— in awe of my mother and what she had been through. Embarrassed as a small child—at the attention she got, at her fame— the feeling ceded to admiration as my high school then college classes matured me to understand what all of it was and what it meant for her to have survived. But my precocious-if-arrogant collegiate mind, there in that café in Philadelphia, for whatever reason, found the screw filing to be an act of futility so mind-numbing that I could not help the slight tone of condescension that entered my voice.

“What I really want to know, Mom, is why people didn’t really resist. You know? I mean, they were outnumbered, right? I mean, how could you just let that happen to you? Take it like it was okay?” This was the most defeated she’d ever looked at me. She, so manhandled by life, could do nothing but muster disappointment in her only daughter. And so she responded by saying nothing.

It occurred to me, just like in my dream: no words.

Essayez de regarder. Essayez pour voir.

In front of her bookshelves, the page her newspaper clipping marked remained open in my hands and I realized I had been standing for an unknowable amount of time. I had conjured this memory of her, in the café, suddenly, without spur. But as I looked back to the yellowed dryness of the newspaper clipping, it suddenly occurred to me that the memory was not, in fact, conjured from nothing. It was there in the article. Perhaps my passing German had neglected it, or perhaps I wanted to unconsciously fail at realizing it, but there it was, seemingly the boldest word in the paragraph. The crashed German war plane. Just after taking off from the Altenburg airstrip. A faulty schraube.

And Philadelphia was beautiful.

And I looked up at her bookshelves, wondering what other impossible stories of false beauty—the best kind—lived in the pages there.

At the shoreline I write my mother’s name in the sand.

The ocean comes, incessant as history, sacred as the whole world, and tries to erase her. I stand between her name and the water, guarding it with my feet.

Like the words of the Torah, the letters fly.

-Evelyn Emma

When my mother died, I stared at her library for a long time, taking out books at random, leaving gaps of slender knowledge, and refiling them as succinctly as they were first positioned. Her bookshelves at oddly inconsistent heights, positioned as precariously as skyscrapers, held fortitudes of knowledge: a lifetime read, dog-eared, margin-noted. Highlighted passages and the passage of her life—perhaps I, a highlight—all that remained of her. I wondered if she wondered what would happen to all of her books when she was gone; if someone would select them, inherit them, cherish them as she had—their multi-colored goodness evidenced by the care and wear. Probably, I thought—not cruelly—they would be donated. By me, of course. A thrift store, for poor browsers to find her words on accident, scrawled into the off-white margins left for fresh ink to bond.

It saddened me that I wasn’t reader enough to keep them.

But before I could part with them (the only things my left-thinking mother could hoard like a modern-day materialist) I withdrew a particular volume in French I did not know. It was entitled Aucun de nous ne reviendra, by a woman of whom I had never heard (pictured, presumably it was her, on the cover) but here, amongst the other texts in various languages, she reminded me of my mother. She didn’t look like her, but the way she hoisted her chin, a pressed cigarette waiting between two fingers…that was my mother. And in the way that moments such as that can succeed to all the moments that will have to be, I realized I would never see her again, and it nearly killed me.

She would have shaken her head at such melodrama.

Flittering through the pages, as I did just to feel their wind, they stopped on their own accord (as books do when they are so marked) by a small, once-folded piece of paper. It was newsprint, the typical age-yellow of the paper clinging to the pages of the book that held it, like a decades-served prisoner so comforted by his cell that freedom is his only fear. The saved page had two highlighted lines: Essayez de regarder. Essayez pour voir. I tried to look for a French-to-English dictionary to see what they meant, but failed, and so pulled the newsprint from the armpit of the spine and unfolded it. It was from 1944 and it was in German. A German text interloping in French print: a 1944 pun at which my mother must have smirked when she placed it. She, of course, being German, could read what was there; I, her shameful American daughter whose childhood was spent pretending away my diversity in sacrifice to the gods of assimilation, knew only a passable bit.

It was a small article, one that didn’t even warrant a picture; a deeply buried (surely) story about a German war plane that had crashed. I stood there, the book in one hand and the loose sheet of paper in the other, wondering how much the propaganda machine ate holes in the story; truthfully, I was shocked it was even printed. It didn’t seem the Reich-way to publicize any—even if small—military defeat; but there it was, black on yellow for the world to see. A crashed German plane. I read crashed, not downed. Apparently, this was a mechanical, rather than Allied, tumbling.

So there it was: my mother’s war relic.

At most it was a cultural artifact from WWII. At least, my mother’s eccentricity. But her only daughter, left as I was with a bundle of paper, held it between finger pad and opposing thumb with such force as to pulverize the print into the dust that she was, that we’d all be, that she almost was: then.

She wasn’t a survivor; that was the name they gave her, afterwards. She was my mother, that fateful, accidental thing between us—a shared body, for a time—that keeps us, through death, through abomination, together. But what I’m afraid of is that I’ll forget her, her face, the way I have my beloved family dog; who I pined for, then cried for, and swore I’d never forget; now just a ripple of audible yawns and the sweet stink of dog breath my fallible memory tries to reconsider. I’m afraid I’ll forget my mother the same way, the way you write a name in sand though the spiteful moon sends waves to melt it away. So I do all I can to collect memories in consideration of nostalgia, worried about a deathbed with nothing to think back on. And the books’ pages go whif.

If the walls of the Altenburg factory were invisible, you’d be able to trace the smokestacks down to cauldrons. Those spires of industry, announcing civilization from the horizon to distant travelers, led through the roof and down to furnaces that were always angry, and I was the educated woman who kept them growling. Or perhaps not. Perhaps any true utility of mine was just a futile rouse, in the existential sense. Maybe, like everyone, I over-underscored my purpose; maybe I counted too many paces to a place, and forgot all about the steps behind. Maybe, I don’t know.

Maybe I was just like the screws that went by.

The factory was an amazing thing. No matter how many days went by, no matter the bizarre looks I received from my comrades, whose eyes were perpetually down, I gazed out. The conveyors that wound along as if dislodged from a tight-wound ball of string, the steam stampers (my name for them), the cauldrons. The walls with no windows. These things, functioning together, taking an inserted material and producing a valuable component: a thing; something useful. Of course I dreaded its use, whatever it was that we were producing at the factory; but I marveled at the ability of construction. The utility of creation. It made me think of motherhood, though I was sure I would never bear a child, no matter how sure I was—that deeply internal holler (like a voice saying, “You will. You will. You will.”)—when I was a little girl. I was an older girl then, and as proof that my squandered potential motherhood had suffocated that internal voice, I was rapt by the gears of the production.

Jesus said, “Forgive them Father, for they know not what they do”; and neither did we. We knew not what we created. Gun muzzles tempted their vicious innards inches from our backs, and so we fed the cauldrons, we stamped the steam, we sorted the screws. (This last thing, my job.) And I was ironic enough to quote Jesus.

Every day for months (I didn’t have the advantage of chalk to hash out, in marks, the days of my imprisonment—how taken for granted they were by my teachers, as they scrawled the chalk to nubs with arithmetic and Latin. I loved, oh how I loved, to read), every day I’d been marched there, the miles to Altenburg, to sort screws on that conveyor. The muzzles behind, buzzing with the audacity of trigger fingers. How audacious the very thought of being human is: such small things with such big designs. And my sorting screws was no more menial than running a country. An army. Than ignoring what was happening in Europe. No, my sorting screws was no more tedious than thinking, even for a second, that being a human is something special.

Some of the screws were as large as my hand (which, wasn’t very large) and some were as small as the pads of my fingertips (which, were quite small) and I had to sort them, as they glided by on treads, roller controlled underneath, into bins according to their size.

Every once in a while, I slipped one of the largest into my apron pocket. I believed (I had to believe, with God so elusive, in something) that the largest were the most important. Because I was an animal, because of gravity, I had to believe the biggest things were the most important. Screws. Men.

I never received a tattooed number. That was lore. That was only in some camps. It meant you were a laborer; so what all the following generations would scoff at was a sign of survival to those who bore them. Tattoos meant you were to be counted, and that counting was a subtle, profane indication of life somehow valuable. They were not used in my camp. My forearms were clean of ink, of blood, so I didn’t have the reassurance of survival. (I know how much it must pain people living today to read that, but I think it is time for those people to start listening to us and not to history. History has never been honest; it is like blank forearm skin, available for anyone to cut and store ink, while I was there. So I know. History is bitter medicine, but it is worse when it is filtered through human imagination.)

There are too many stereotypes to account for, these so many years later. It’s the negative sublime, the thing you stare at and cannot describe because it is a palette the colors of our brains cannot use to paint. It is experiencing the white light of the divine, and pondering why it so seldom shines. Why miracles only happen in the Torah.

How does one beautifully describe emptiness? Silence? These words are near useless.

The endless elementary schools, the endless beautiful young children with their hopeful schoolteachers, asking questions though only half-interested—perked up to not be rude, and I, expected to warm them with a smile, an anecdote, a cheerfully foreign accent. Would it pain them to know the traces of langue étrangère they heard in my voice were German? Sometimes the schoolteachers bake yellow-star cookies with Jude in black icing on them, which are eaten ravenously by the children.

According the Nuremburg Laws, I was a “Mischling of the first degree,” which were, “Persons descendent from two Jewish grandparents but not belonging to the Jewish religion and not married to a Jewish person on Sept. 15, 1935.” This bought me time; this and that I inherited the luckier traits of my two other grandparents, leaving me all sand-blond hair and sea-blue eyes; that and of course the fact that I’d never stepped foot in a synagogue. But those things only saved me for so long.

Once, back in the Altenburg factory, a comrade saw me put one of the large screws into my apron pocket and exclaimed, “Do not do that; you will be killed.”

To which I responded, “I am dead already.”

But the muzzle never nuzzled my nape, or my back, or my head, for that matter. Perhaps they never saw. Or perhaps the soldiers were just as bored as they looked. Most of them were beautiful children with misguided schoolteachers, too. I was efficient enough to sort with my non-dominant hand, so no one seemed to pay much attention to the other hand, buried deep into the pocket, with the screw.

Infrequently but steadily, I snuck my hand into the pocket, which also contained a nail file, and clumsily brushed the abrasive grain (my father’s three-hour beard stubble!) against the shaft of the screw. Over time—this was all we had: a surplus, a deluge—I learned to file with delicacy, drawing the file back and forth with only the tips of my fingers (second knuckle and above) so that the sinews of my forearm didn’t flex or undulate. Eventually, I could wear down the threads of the screw’s shaft to near nothing, smoothing flat what was designed to grip, before withdrawing the screw, placing it in its bin, and beginning again with another.

When I arrived at the camp near Altenburg from Dresden, they found the file in my pocket (this had been a different pocket; I had been stripped of my previous clothes, made to stand naked long enough to be humiliated, before being given new rags), as they found all of the things in the world that had belonged to me. They took everything, but the file. This they let me keep, out of mockery, to laugh at the absurdity that, despite my haggard condition, I could do something as superficial as shape my nails. As my teeth rotted, as my hair thinned, as my muscles betrayed the bone underneath, as my tongue became sandpapered like the blade of the file itself; they’d frequently ask to see my nails—the round clean shape of them, the kept cuticle, the finish of an ocean-loved shell. They’d call to me during marches, “Show us the nails,” and I would raise my hands—surrender and spectacle—for them to examine. And their yellowed laughter would seem to catch the sky, echo as if we were all cloistered somewhere. The sound of it triumphant as church bells, psychotic as air-raid sirens, alluring as isle-stayed Sirens, noxious like a snake’s kiss. They never worried I’d stab someone: them, myself. The joy of the anachronism blunted their boredom and I had fine nails until they began to break. Eventually, they forgot all about it, and so I had the file, and the screws.

I didn’t know what good filing the screws would do; I just had to have purpose, some rationality. I had to have something that was mine, just a little agency I could call upon that was geared toward the future. Even if it was a carrot on a string, even if it was so close to nothing that I could laugh at myself for even thinking of it (laughter, even in self-hatred, was balm). It was breath while I was submerged, and so I filed clean the threads of a screw or two a day, no more superficial an action as any other we demand our simple bodies to do. But, of course, the screws had to go to something. We all knew what the bellowing factory was a part of, even if we didn’t see the direct result, and it was a human thing for me to do, to hold out hope that my extended toe into the aisle might cause one of them to trip.

I wondered, flightily, as girls did, what people would think and how they would remember all of it. I knew it would end, eventually. How like everything. But posterity—what would it think of this final conclusion: the realization that despite our millennia of egotistical arrogance in thinking we were the champions of the Earth, that we were truly tiered at some class far below the animals. A hundred years hence, when the necessary reality ceded to the eventual mythology, how would the writers appropriate what that was for prose? They would have to, of course; the sound waves from our mutable voices would only travel so far; but how would the new voices sound? How would they carry the legacy of this suffering? Could a poem ever be properly impregnated with the dissonant fugue of such rancid melodies? I feared the noblest of future scribes would only be able to get this as a myth, a Trojan Horse, a golden-threaded labyrinth, the words of the Torah flying away from the fire of their own burning pages; but perhaps that is all the past is: a broken circle beyond which the voices of sufferers tremble out into nothing.

A recent evening, I had a nightmare. I was on an interstate, heading from somewhere to somewhere, but there wasn’t a single exit offering reprieve from the infinite stretch. All that existed was flat road—long grey expanse bisected by yellow paint and flanked by high concrete dividers. No shoulder, no green signs marking the impending escape routes. It moved on forever, road to horizon like the prize-winning photographs of the American desert, but I was horrified. The interstate in its grandiosity, linking one side of the country to the other, zagging like a heartbeat blip across the landscape: north/south plummets and hikes with marginal east/west progress. My rational mind would know that ocean was inevitable, but my dreaming mind interpreted Eisenhower’s web as suburban murder. It was all going and no stopping, all destination and no journey. How horrible it was to go on forever and never get off. How horrible to see all the things one could experience just beyond the shoulders, but be caught in a racing thing only interested in forward so that all those roadside attractions became blurs of the stuff memory lusts for, but like in dreams, are gone the more one tries to remember them after waking. It’s because of words; it’s because we try to use words to describe dreams, and they are not the things of words. They are beyond words. Dreams and nightmares both.

I remember when my mother first told me of the screws.

We were on a trip to Philadelphia, a city she loved; it was the first place she lived in America and I always thought this brought her some kind of affection for the place I thought was rather dirty. She wanted to walk me around her old neighborhood, a place she painstakingly plotted out on maps but had trouble, on the ground, locating. We wandered, presuming which direction to go (her head shaking negative at how quickly, how much, things changed) until we eventually just decided that where we were was in fact the neighborhood in which she once lived. It was a simple self-deception, the ruse of it just a platform of nostalgia; and for her, it worked. She gleamed with pride at the concrete of the sidewalks upon which she may or may not have ever walked. I was less astonished, the evidence of this in my face or in the small action of my kicking away a piece of trash rather than stepping over it. To all of this, she replied, “What is the greater talent, loving Paris? A place everyone knows to love? Or loving Philly, a place you have to work to love? Isn’t there a greater talent in loving something that isn’t so obvious? Expectations are really just a matter of consensus.”

“Beauty is Truth,” I said, quoting a literature class, of which I was then in the throes. I was a college student then, and pretention was no less an exercise of common course than waking to resume breathing—having forgotten that one breathes all through sleep.

“Beauty is no such thing,” she said, becoming serious. “Truth—who’s truth? Beauty is most in what is false, what isn’t obvious.”

She told me about the filing of the screw threads in a café toward the center of the city, where we sat as two women with independent drinks and a shared cheese Danish. She explained the nail file, the clandestine wearing-away of a screw-or-two-a-day in opposition of some phantasm. She told that story with a sense of pride that I could not understand; I could not see the heroism, the valiance she purported to own in this small act of courage. I was, generally—as most people were and should have been— in awe of my mother and what she had been through. Embarrassed as a small child—at the attention she got, at her fame— the feeling ceded to admiration as my high school then college classes matured me to understand what all of it was and what it meant for her to have survived. But my precocious-if-arrogant collegiate mind, there in that café in Philadelphia, for whatever reason, found the screw filing to be an act of futility so mind-numbing that I could not help the slight tone of condescension that entered my voice.

“What I really want to know, Mom, is why people didn’t really resist. You know? I mean, they were outnumbered, right? I mean, how could you just let that happen to you? Take it like it was okay?” This was the most defeated she’d ever looked at me. She, so manhandled by life, could do nothing but muster disappointment in her only daughter. And so she responded by saying nothing.

It occurred to me, just like in my dream: no words.

Essayez de regarder. Essayez pour voir.

In front of her bookshelves, the page her newspaper clipping marked remained open in my hands and I realized I had been standing for an unknowable amount of time. I had conjured this memory of her, in the café, suddenly, without spur. But as I looked back to the yellowed dryness of the newspaper clipping, it suddenly occurred to me that the memory was not, in fact, conjured from nothing. It was there in the article. Perhaps my passing German had neglected it, or perhaps I wanted to unconsciously fail at realizing it, but there it was, seemingly the boldest word in the paragraph. The crashed German war plane. Just after taking off from the Altenburg airstrip. A faulty schraube.

And Philadelphia was beautiful.

And I looked up at her bookshelves, wondering what other impossible stories of false beauty—the best kind—lived in the pages there.

At the shoreline I write my mother’s name in the sand.

The ocean comes, incessant as history, sacred as the whole world, and tries to erase her. I stand between her name and the water, guarding it with my feet.

Like the words of the Torah, the letters fly.

Jeffrey S. Markovitz is a Professor of English and Creative Writing and is the Director of the Creative Writing Certificate Program at the Community College of Philadelphia. His fiction, non-fiction, and poetry have appeared in a variety of print and online journals. His short-story chapbook, —for Olivia, was published by The Head and the Hand Press (2013) and his novel, Into the Everything, was published by Punkin Books (2011). He can be reached via his website: jeffreysmarkovitz.wordpress.com

A 2016 Pushcart Prize nominee, Jeff's story can be found in Issue 10 of Glassworks.