Interview

gENDER, rACE, AND sEXUALITY THROUGH THE EYES OF CREATOR CHRISTINE SLOAN STODDARD

BY aLEKSANDR cHEBOTAREV, aNGELA fAUSTINO, & sAM fINE

March 2021

Often, when we think of creatively inclined people, we see them as one of the following: a painter, a photographer, a writer. But, we don’t often think of someone as all of these things. Christine Sloan Stoddard, an American-Salvadoran author based in Brooklyn, New York, is a great example of someone who embodies all of the occupations that come to mind when we think of a creative person.

As a woman who has seen the inequality in this world, Stoddard focuses her work on exactly this, therefore bringing justified awareness through her works of art and literature. In this interview, Stoddard discusses the depth of her characters, her multimedia elements, and the reasons why she can write and create the masterful works that she has.

As a woman who has seen the inequality in this world, Stoddard focuses her work on exactly this, therefore bringing justified awareness through her works of art and literature. In this interview, Stoddard discusses the depth of her characters, her multimedia elements, and the reasons why she can write and create the masterful works that she has.

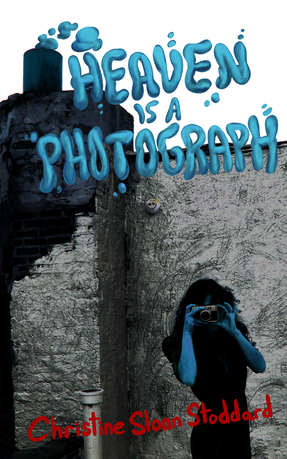

Glassworks Magazine (GM): In your poem “BFA,” from your book Heaven is a Photograph, you discuss the struggle between a career that is “practical” and one that is passionate. How does this poem reflect your own decision to pursue a career in the arts?

Christine Sloan Stoddard (CSS): Previously, I worked in journalism while hustling in the arts on the side. Now it’s the opposite: while I still do some journalism and communications work, I make my living mainly from the arts now. Since high school, I’ve been working toward this goal and was finally able to achieve it a couple of years ago. It involved a lot of planning and many personal sacrifices, but I could not be more grateful. I’ve pursued a career in the arts because creative expression is my language. I never felt truly happy or fulfilled in a traditional office setting and knew that I had to be my own boss. In college, one mentor told me she could only ever imagine me working for myself. Another said that it sounded like being an artist was the only career that would satisfy me. Both of these mentors were onto something, but I don’t regret my time in journalism. Journalism can be a noble profession and you always meet fascinating people in the field. Mass media informs my art-making, as well as many of the business decisions I make as an artist.

Unfortunately, our society does not offer a lot of support for artists and there is no set path for becoming one, or at least for making a living as one—To clarify, anybody can make art and be an artist at any time; I don’t believe that making a living from your art is what makes you an artist. Many of us slowly start making a name for ourselves while working day jobs because we have to feed ourselves and pay rent. Meanwhile, we develop various revenue streams that will allow us to eventually leave our day job. Unless you have a trust fund or a rich spouse, you don’t have many other options for becoming a full-time artist. I made my choice because even a day job many people find exciting and rewarding—a dream job for many—was not doing it for me. I enjoyed doing journalism work sometimes, on a freelance basis but not full-time. My creative pull is too strong, as is my hatred of clickbait.

Christine Sloan Stoddard (CSS): Previously, I worked in journalism while hustling in the arts on the side. Now it’s the opposite: while I still do some journalism and communications work, I make my living mainly from the arts now. Since high school, I’ve been working toward this goal and was finally able to achieve it a couple of years ago. It involved a lot of planning and many personal sacrifices, but I could not be more grateful. I’ve pursued a career in the arts because creative expression is my language. I never felt truly happy or fulfilled in a traditional office setting and knew that I had to be my own boss. In college, one mentor told me she could only ever imagine me working for myself. Another said that it sounded like being an artist was the only career that would satisfy me. Both of these mentors were onto something, but I don’t regret my time in journalism. Journalism can be a noble profession and you always meet fascinating people in the field. Mass media informs my art-making, as well as many of the business decisions I make as an artist.

Unfortunately, our society does not offer a lot of support for artists and there is no set path for becoming one, or at least for making a living as one—To clarify, anybody can make art and be an artist at any time; I don’t believe that making a living from your art is what makes you an artist. Many of us slowly start making a name for ourselves while working day jobs because we have to feed ourselves and pay rent. Meanwhile, we develop various revenue streams that will allow us to eventually leave our day job. Unless you have a trust fund or a rich spouse, you don’t have many other options for becoming a full-time artist. I made my choice because even a day job many people find exciting and rewarding—a dream job for many—was not doing it for me. I enjoyed doing journalism work sometimes, on a freelance basis but not full-time. My creative pull is too strong, as is my hatred of clickbait.

GM: Has the pandemic altered your view of a career in the arts?

CSS: The pandemic hasn’t really altered my decision to pursue a career in the arts. I’m still doing what I was doing before the pandemic, just with more virtual or socially distanced options. Thanks to Zoom and other streaming services, I’ve done everything from serve on museum and gallery panels to perform in Off-Broadway plays, all from the comfort of my apartment.

Right now, my biggest client project is a commission of 10 murals in a group home. Residents will be moving in at the end of the year, so I’ve been hired to make a mural in each of their bedrooms. I go to the building everyday and work entirely by myself; nobody else is on site because the renovation was completed right before New York City’s COVID-19 shutdown. With the building close to my home, mural-making has been perfect pandemic work. Only a few years ago, I would’ve dreamed of a commission like this and, now, thanks to hard work and a little luck, it’s a reality.

GM: To delve further into your poem, “BFA,” we were drawn to these particular lines: “my camera is my soul/ but you have a stomach/ feed your stomach.” What made you decide to pursue photography with this concern in mind?

CSS: I would first like to clarify that the book is a work of metafiction, not nonfiction. My protagonist chooses photography as the principle thrust of her creative practice. For me, photography is just one aspect of my creative practice. My protagonist chooses photography for the same reasons that many artists work with photography today: photography has more practical application today than painting and drawing does. Photography saturates our visual culture in a way that illustration does not. Look at our books, magazines, advertisements, websites, and more. You will see that photography dominates. Unsurprisingly then, there’s a much higher commercial demand for people who know how to take and edit quality digital photos than there is a demand for people with illustration skills, even digital illustration. In the fine art world, digital photography is an increasingly popular medium because it’s much less time consuming than painting and drawing, so you can realize an idea much more quickly. In many ways, it’s cheaper, too. You don’t need canvas, paper, paints, pencils, or charcoals, which must be constantly replaced or replenished, and you can make dozens of images in a single hour.

GM: We see you have quite a history with both written literature and film. Which were you first passionate about? Do your poetic and filmmaking processes influence each other, or do you keep them separate?

CSS: The pandemic hasn’t really altered my decision to pursue a career in the arts. I’m still doing what I was doing before the pandemic, just with more virtual or socially distanced options. Thanks to Zoom and other streaming services, I’ve done everything from serve on museum and gallery panels to perform in Off-Broadway plays, all from the comfort of my apartment.

Right now, my biggest client project is a commission of 10 murals in a group home. Residents will be moving in at the end of the year, so I’ve been hired to make a mural in each of their bedrooms. I go to the building everyday and work entirely by myself; nobody else is on site because the renovation was completed right before New York City’s COVID-19 shutdown. With the building close to my home, mural-making has been perfect pandemic work. Only a few years ago, I would’ve dreamed of a commission like this and, now, thanks to hard work and a little luck, it’s a reality.

GM: To delve further into your poem, “BFA,” we were drawn to these particular lines: “my camera is my soul/ but you have a stomach/ feed your stomach.” What made you decide to pursue photography with this concern in mind?

CSS: I would first like to clarify that the book is a work of metafiction, not nonfiction. My protagonist chooses photography as the principle thrust of her creative practice. For me, photography is just one aspect of my creative practice. My protagonist chooses photography for the same reasons that many artists work with photography today: photography has more practical application today than painting and drawing does. Photography saturates our visual culture in a way that illustration does not. Look at our books, magazines, advertisements, websites, and more. You will see that photography dominates. Unsurprisingly then, there’s a much higher commercial demand for people who know how to take and edit quality digital photos than there is a demand for people with illustration skills, even digital illustration. In the fine art world, digital photography is an increasingly popular medium because it’s much less time consuming than painting and drawing, so you can realize an idea much more quickly. In many ways, it’s cheaper, too. You don’t need canvas, paper, paints, pencils, or charcoals, which must be constantly replaced or replenished, and you can make dozens of images in a single hour.

GM: We see you have quite a history with both written literature and film. Which were you first passionate about? Do your poetic and filmmaking processes influence each other, or do you keep them separate?

|

CSS: I have always been drawn to both and indeed studied both in undergrad. But I started writing first because it was something I could do on my own without the material and logistical concerns of filmmaking. It’s like my husband jokes, if you can’t write a book, that’s all on you. Pulling together everything necessary to make a film is more complicated and expensive. Plus, there’s much more of an industry attached to film. That’s why they call it show business. Don’t get me wrong, there’s still a poetry industry (just look at certain MFA programs and vanity presses!), but the financial stakes are much lower than in film. I’m still trying to overcome all of the systematic barriers that non-white male directors face. I don’t think I have it in me to stop trying.

|

When I first sit down to write or create, I don’t necessarily think, “Oh, this is a story about race” or “This is a story about religion.” I think in terms of story. |

My mother cultivated my deep love for books and libraries, while my father, a director of photography for news and documentaries, helped train my filmmaker’s eye from a young age. Both of my parents love movies and theatre. We went to many free film festivals and plays in the Washington, D.C. area when I was growing up. I remember attending many screenings at the National Gallery of Art and productions at the National Conservatory of Dramatic Arts, to name a couple favorite venues. Exposure to a wide variety of storytelling inspired me and allowed me to hone my sensibilities.

To paraphrase the French screenwriter and poet Jacques Prévert, cinema and poetry are the same. My undergrad screenwriting professor always told us that the form and pacing of a screenplay are more similar to poetry than fiction writing. You write in beats. My poetic and filmmaking processes definitely influence one another. I don’t think I could separate them if I tried.

GM: We notice that your topics range from things like gender and sexuality to race and religion. With this in mind, do you find yourself using traditional trade craft as opposed to pushing the boundaries in your pieces regarding race or ethnicity or gender and sexuality? Do you prefer one over the other in regard to these topics?

CSS: I don’t necessarily aim to push boundaries in form, though I have more interest in doing so in regards to content. Mostly, I go where my intuition and imagination take me, with personal experience and research to ground me. When I first sit down to write or create, I don’t necessarily think, “Oh, this is a story about race” or “This is a story about religion.” I think in terms of story. Who’s my protagonist? Why are they intriguing? What do they want? If you ask me, this is a much more organic approach to storytelling. Themes emerge on their own. It’s up to my audience to find and interpret them.

To paraphrase the French screenwriter and poet Jacques Prévert, cinema and poetry are the same. My undergrad screenwriting professor always told us that the form and pacing of a screenplay are more similar to poetry than fiction writing. You write in beats. My poetic and filmmaking processes definitely influence one another. I don’t think I could separate them if I tried.

GM: We notice that your topics range from things like gender and sexuality to race and religion. With this in mind, do you find yourself using traditional trade craft as opposed to pushing the boundaries in your pieces regarding race or ethnicity or gender and sexuality? Do you prefer one over the other in regard to these topics?

CSS: I don’t necessarily aim to push boundaries in form, though I have more interest in doing so in regards to content. Mostly, I go where my intuition and imagination take me, with personal experience and research to ground me. When I first sit down to write or create, I don’t necessarily think, “Oh, this is a story about race” or “This is a story about religion.” I think in terms of story. Who’s my protagonist? Why are they intriguing? What do they want? If you ask me, this is a much more organic approach to storytelling. Themes emerge on their own. It’s up to my audience to find and interpret them.

GM: In your poetry, you make many allusions to gender and femininity; “A Baby Girl,” “Defining a Slut,” from your book, Naomi & the Reckoning, and “Mestiza Girl,” from your book Harlem Mestiza: “I am the tangle of tissue /a woman star in the /constellation of humanity.” How does your experience as a woman inspire these poems and other pieces you have written?

CSS: Write what you know, right? It does amuse me that men aren’t asked if their experience as a man inspires their writing or art. I have written from male (and non-binary) perspectives, but I usually write from a woman’s point of view because those are the stories I am most passionate about telling. To be a woman in almost any society is to be treated as lesser. Lived experience tells me that and it’s that lived experience that propels me to write pieces like these. Even if I’m fictionalizing the character, setting, and events, I know the core of this character and her circumstances because I have lived some version of it. (I mean that very figuratively.)

GM: In “Saved” from Harlem Mestiza, you discuss the struggle of double consciousness in biracial children with one white parent: “You may be ‘brown and white’ /in your rage-filled heart, /but the world rejects this answer.” As a Salvadoran-Scottish-American writer, how do your various backgrounds interact in your literature? What role does your family heritage play in inspiring your work?

CSS: Similarly to the last question, I cannot help but be inspired by my lived experience and experiences similar to my own. That being said, I was not raised in El Salvador or Scotland and had no firsthand knowledge of either place until I was an adult, but I’ve always been immensely curious about them. As a first-generation Salvadoran immigrant, my mother never wanted me to have a relationship with her homeland, which was ravaged by war. Meanwhile, my father is American, but the pride in Scottish heritage is strong. My father’s family came to the U.S. from Scotland and Northern England (a borderland) a few generations ago. Because there was always a sense of taboo distance from both places, I initiated my own research and trips to El Salvador and Scotland. I studied in Scotland one summer in undergrad and went to El Salvador for an artist residency in grad school. I wanted to know more about the cultures and sensibilities that shaped my parents, who in turn shaped me. This is a natural impulse. DNA kits and genealogy services are all the rage, so it’s not like I’m the only one who wants to know about my ancestors and ancestral homes. Lived experience and research intersect organically as I write, drawing from my knowledge and imagination.

GM: Several of your works include Spanish language: “María la Mirona,” from your book Harlem Mestiza, “Doña Azucena,” and your work, Mi Abuela, Queen of Nightmares. How does using a language other than English in your work influence your aesthetic?

CSS: I don’t consider it an aesthetic; that implies an affectation. It’s a means of conveying a narrative. If Spanish helps convey the narrative for a certain character and story, then I use it. If it doesn’t, then I don’t.

GM: As a follow-up question, do you have any concerns about non-Spanish speakers feeling dissuaded from reading those particular pieces written in Spanish?

CSS: Write what you know, right? It does amuse me that men aren’t asked if their experience as a man inspires their writing or art. I have written from male (and non-binary) perspectives, but I usually write from a woman’s point of view because those are the stories I am most passionate about telling. To be a woman in almost any society is to be treated as lesser. Lived experience tells me that and it’s that lived experience that propels me to write pieces like these. Even if I’m fictionalizing the character, setting, and events, I know the core of this character and her circumstances because I have lived some version of it. (I mean that very figuratively.)

GM: In “Saved” from Harlem Mestiza, you discuss the struggle of double consciousness in biracial children with one white parent: “You may be ‘brown and white’ /in your rage-filled heart, /but the world rejects this answer.” As a Salvadoran-Scottish-American writer, how do your various backgrounds interact in your literature? What role does your family heritage play in inspiring your work?

CSS: Similarly to the last question, I cannot help but be inspired by my lived experience and experiences similar to my own. That being said, I was not raised in El Salvador or Scotland and had no firsthand knowledge of either place until I was an adult, but I’ve always been immensely curious about them. As a first-generation Salvadoran immigrant, my mother never wanted me to have a relationship with her homeland, which was ravaged by war. Meanwhile, my father is American, but the pride in Scottish heritage is strong. My father’s family came to the U.S. from Scotland and Northern England (a borderland) a few generations ago. Because there was always a sense of taboo distance from both places, I initiated my own research and trips to El Salvador and Scotland. I studied in Scotland one summer in undergrad and went to El Salvador for an artist residency in grad school. I wanted to know more about the cultures and sensibilities that shaped my parents, who in turn shaped me. This is a natural impulse. DNA kits and genealogy services are all the rage, so it’s not like I’m the only one who wants to know about my ancestors and ancestral homes. Lived experience and research intersect organically as I write, drawing from my knowledge and imagination.

GM: Several of your works include Spanish language: “María la Mirona,” from your book Harlem Mestiza, “Doña Azucena,” and your work, Mi Abuela, Queen of Nightmares. How does using a language other than English in your work influence your aesthetic?

CSS: I don’t consider it an aesthetic; that implies an affectation. It’s a means of conveying a narrative. If Spanish helps convey the narrative for a certain character and story, then I use it. If it doesn’t, then I don’t.

GM: As a follow-up question, do you have any concerns about non-Spanish speakers feeling dissuaded from reading those particular pieces written in Spanish?

|

CSS: I am not concerned about dissuading readers of these particular works. They are aimed for readers with an intermediate level of Spanish, or at least the willingness to look up words. These works are not for readers who do not possess that skill or willingness to learn. Some of my works are aimed at a general audience; these are not. I do not feel obligated to cater to everyone all of that time. As a girl, I was socialized with feeling that burden too much of the time. I felt that way because of gender expectations, as well as the expectations thrust onto a child of an immigrant. Then there are the expectations I felt weighing down on me because my class and material circumstances differed so much from my parents’ upbringing. Now I wish to rid myself of this burden—and I have. This is one way I say “no,” and I do it firmly.

|

"I studied in Scotland one summer in undergrad and went to El Salvador for an artist residency in grad school. I wanted to know more about the cultures and sensibilities that shaped my parents, who in turn shaped me. This is a natural impulse." |

GM: We’ve noticed that you sometimes write exclusively in lowercase letters; for example, “The Almost-Rape,” from your poetry collection Naomi & the Reckoning, and “The Dead Girl Artist’s Scientific Method” from your book Heaven is a Photograph. What is the significance of omitting capital letters to you? Is there an intended meaning behind this?

CSS: I tend to take this approach when my character or narrator feels timid and small. It is a means of embodying that frailty. I do it out of instinct. Many people might not believe this, but I know all too well the desire to shrink and even become invisible. I have empathy for my characters when they also feel this way.

GM: It’s apparent that your work consists of many topics relevant in today's society. During a time where racial injustice and inequality in America has reached a zeitgeist, what role do artists and writers have to play in fostering the morals of the nation?

CSS: Racial injustice and inequality in America may define the current zeitgeist, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t concerns before this time. They’ve only just become mainstream concerns. And by that, I mean enough straight, white, able-bodied men have finally deemed these concerns relevant. It’s not like that happened magically or of their own volition, either. There’s been a lot of pressure, especially from Black voices that are being heard at long last. It’s about damn time, but the struggle and need for change are also far from over.

Artists and writers are naturally creative and our imagination allows us to consider new possibilities. That includes societal possibilities. I’m not a fan of the word “moral” because it implies too much of a binary of “right” and “wrong” for my taste. Rather, I believe in artists’ responsibility to justice and equitability. How they achieve this is up to them. I’m not usually a fan of didactic work, but I’m also not interested in being a grand arbiter of taste. This is why building a career as a critic was never a viable option for me. I believe that there are many ways to be an artist and many ways to make art—and that thrills me. I would rather have a multitude of voices than too few. When people ask me if I’m concerned about competition and the devaluing of artists’ labor, I would say that’s a concern with Capitalism, not art. Art and the art market may be related but they are separate entities.

There are so many unknowns in any artist’s career. It is mainly my hope to keep creating and honoring my vision. Whenever someone tells me that my work has had an impact on them, I feel encouraged because impacting even just one person has value.

GM: As an artist, how have you adapted to the pandemic and its restrictions? How do you reach your audience in a time of isolation and distancing?

CSS: I tend to take this approach when my character or narrator feels timid and small. It is a means of embodying that frailty. I do it out of instinct. Many people might not believe this, but I know all too well the desire to shrink and even become invisible. I have empathy for my characters when they also feel this way.

GM: It’s apparent that your work consists of many topics relevant in today's society. During a time where racial injustice and inequality in America has reached a zeitgeist, what role do artists and writers have to play in fostering the morals of the nation?

CSS: Racial injustice and inequality in America may define the current zeitgeist, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t concerns before this time. They’ve only just become mainstream concerns. And by that, I mean enough straight, white, able-bodied men have finally deemed these concerns relevant. It’s not like that happened magically or of their own volition, either. There’s been a lot of pressure, especially from Black voices that are being heard at long last. It’s about damn time, but the struggle and need for change are also far from over.

Artists and writers are naturally creative and our imagination allows us to consider new possibilities. That includes societal possibilities. I’m not a fan of the word “moral” because it implies too much of a binary of “right” and “wrong” for my taste. Rather, I believe in artists’ responsibility to justice and equitability. How they achieve this is up to them. I’m not usually a fan of didactic work, but I’m also not interested in being a grand arbiter of taste. This is why building a career as a critic was never a viable option for me. I believe that there are many ways to be an artist and many ways to make art—and that thrills me. I would rather have a multitude of voices than too few. When people ask me if I’m concerned about competition and the devaluing of artists’ labor, I would say that’s a concern with Capitalism, not art. Art and the art market may be related but they are separate entities.

There are so many unknowns in any artist’s career. It is mainly my hope to keep creating and honoring my vision. Whenever someone tells me that my work has had an impact on them, I feel encouraged because impacting even just one person has value.

GM: As an artist, how have you adapted to the pandemic and its restrictions? How do you reach your audience in a time of isolation and distancing?

"Racial injustice and inequality in America may define the current zeitgeist, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t concerns before this time. They’ve only just become mainstream concerns." |

CSS: The pandemic has been stressful, of course, but it hasn’t changed the fact that I spend long hours by myself, devoting myself to my creative process. Otherwise, I keep to myself in person and find means of virtually collaborating with my fellow artists. My parents both lived through war, and they’ve passed onto me that joy and gratitude are survival tactics at all times, but especially in times of struggle. You must find beauty and pleasure without disregarding suffering. That doesn’t mean it’s easy; I am persevering nonetheless.

|

I am not having any trouble reaching my audiences in a time of isolation because I already had a following for different aspects of my creative practice. I say this with some amount of exhaustion because this following has taken a decade to cultivate. I am no overnight success—not that such a thing truly exists. What I have learned is that different media and platforms serve different purposes and reach different audiences. Not everything I create is for everyone, but over the years, I’ve developed a sense of how to find an audience. I will simply say that to any students or other emerging artists reading this: do not be discouraged. Keep at it.

Read more about Stoddard's work at her website

Read our review of Naomi & The Reckoning by Poetry Editor Angela Faustino

Read our review of Naomi & The Reckoning by Poetry Editor Angela Faustino