|

We are pleased to present our annual flashglass anthology! Comprised of all flash works originally published online at rowanglassworks.org in 2018, this anthology is available for online viewing and for purchase in print. Copies will also be available for $5 cash at the AWP Conference and Bookfair in Portland, Oregon this March and at our upcoming readings at Rowan University.

Thanks to all our contributors for allowing us to present their work this year!

By Glassworks Magazine in flashglass 24 pages, published 12/31/2018

an anthology of work originally published at rowanglassworks.org

0 Comments

I spritz the countertop. I hate grime. John hates spray near his food. “Could you not?” he says, pulling his salsa closer. “Natural and biodegradable are different than ingestible.” I keep my eyes on the rag, scrubbing over the spills. Our kitchen is large, beautiful. John sits at a barstool, three feet from where I’m wiping off residue. No spray has come close to him. “Maybe,” I say. “But this won’t hurt you.” “Prove it.” Then I remember an argument seven years earlier. ~

“Never go to bed angry,” my mom had advised before my wedding. John came in. He held a bottle of Clorox. He stood in front of me. Spritz. I squeezed my eyes shut and pursed my lips. Spritz. I held my hands in front of my face, grimacing, tucking my chin, blotting the droplets. Spritz. “Stop it. I’m listening. Just tell me what you want to say.” “You’re nasty,” John said. “You need to be cleaned.” Spritz. “Leave me the fuck alone!” I yelled, licking my lips. I used my thumbs to wipe across my eyes and cupped my hand to spit into it. I wiped the saliva on my thigh. “You seem angry,” he said, sitting down. “There’s no need to raise your voice.” I tucked my knees to my chest and wrapped my arms around them, burying my head in the space between them while I blinked. I held my breath. “It’s okay,” John said. “You’re just upset. Why don’t we try to talk now?” His hand caressed my back. I shook my head, and John left. I heard water running. My eyes stung. No matter how hard I wiped them, they burned. I made it worse. Wiping. Crying. The faucet turned off. Then I felt it. Cold water poured down my face and neck. My shirt sopped. I shivered. John had dumped a pitcher of water over me. When I looked up, he was on his knees in front of me, his hands on my legs. “Will you talk to me now please?” ~ I look John in the eyes again, lifting the bottle of cleaner and aiming into my mouth. He scoops salsa with a chip. I squeeze the trigger. He is right. It hurts. Not at first, like some things. Later. When you realize what you’ve done. Sarah Mouracade has lived in Anchorage, Alaska for more than a dozen years and intends to stay there. She is completing her MFA in creative writing at the University of Alaska Anchorage, working as the Communications Manager for a local nonprofit, and enjoying every moment she has with her son. Her work has been published in The New York Times, Cirque Journal, Alaska Women Speak, and The Anchorage Press. You can find samples of Sarah’s work at www.sarahmouracade.com.

For Josh In alternating day and night shifts, you work at O’Hare, preparing the albatross. Outside the hangar, the hours choke with exhaust. Wearing, as always, your blue Dickies, you de-ice planes’ wings each winter. How long it lingers—the scent of jet fuel in the fold of your cargo pockets. Last year, once the wind was less cruel and the ice cracked in plates on the surface of the Chicago River, you bought a camera to journal the rites foreshadowing spring. Those late winter weeks wake the same. Salt washing from the sidewalks. The Ferris wheel illuminated in stillness at Navy Pier. The camera brought you awe, burning among the constellations, my brother who never sees the stars. Our father thinks there should be more evenings ending in fireworks, but you’ve seen enough light falling into Lake Michigan. When Delta finally granted you three vacation days, you waited six hours on standby for a seat to LA. The night you walked along Hermosa Beach, a rocket launched—a prisoner’s cinema of blown glass escaping to the sea—its contrail a gash on the horizon hours after you took the photograph. You had searched skyscrapers for beauty; it arrived, beyond the high-rises, sudden and impermanent in a smoke line on the face of the sky. In an ocean that gave itself to fire. Jessica Conley teaches literature at The Steward School in Richmond, Virginia. She is also an MFA Poetry student at Virginia Commonwealth University where she earned her BA in English and MA in Secondary English Education. She has been published in literary magazines such as The Gordian Review and Not Very Quiet. all goldfish while the water washes over. She moves her head from side to side. As if she can catch the rain. My father has taken off again. Strapped a valise to the top of the car. Been gone this time for two weeks now. Mother says things like “he loves me” as if she can it make it true. My brother says things like my father’s a trap, and it would be good for my mother to melt. I say things like we could maybe bring her an umbrella, and these are our parents, you know? In the front yard, tree branches in curls. Floodwaters stitching the street. You don’t remember how awful dad was, my brother says. The women he’d bring home. How they’d sit out front in the car with our father, their blue eyelids, their bobbly heads. How we became dolls whose legs couldn’t move. And so, now, when my father floats his car back up the driveway, and my mother shimmies like a frenzy fish moving towards food, I am not surprised. We will go back to like always. Still, for a flicker, I thought my brother could escape, but instead, he sloshes towards my father, helps him heft the valise off the top of the car, and that’ll make how many times in a row?  Francine Witte is the author of four poetry chapbooks and two flash fiction chapbooks. Her full-length poetry collection, Café Crazy, has recently been published by Kelsay Books. She is a reviewer, blogger, photographer, and a former English teacher. She lives in NYC.  the crunch that came from the yeasty bread fresh out of the oven, crept past the coffee saucer, past the hollow you left in my heart, past the rice all grained up and waiting in the airproof jar, past the soapdish and the dishes in the drainer all twinkly and clean, past the worm waiting inside the counter apples, past the invisible chain of you that is tight around my neck, my finger, my everywhere, past the chip in the bowl that is holding the pear that you bit into, thought was too sour, the way you said we had gone sour, and put it back in its place until you decide if you ever want to give it another try.  Francine Witte is the author of four poetry chapbooks and two flash fiction chapbooks. Her full-length poetry collection, Café Crazy, has recently been published by Kelsay Books. She is areviewer, blogger, photographer, and a former English teacher. She lives in NYC.  curve over the top of a green glass vase at the center of the oak table. I’ve cut the flowers too long so after four days they look translucent and gorgeously weary, like dancers in costume after a rehearsal. The sound of the occasional car drifts through the open windows. Further off, someone is moving their lawn. In the late summer light I sit down with a notebook and try to write out lists of tasks I’ve been thinking about for weeks. All the cleaning I have to do, the new job I need to find, the friends I should try to get back in touch with, the friends I’ve lost for good. I do my best to will my hand into writing out the new healthy diet I will follow and the contingency plans I should make, just in case things don’t go the way the doctors hope. Then there are the other lists, the ones that will include all the trips I’ll take if I keep living and the love I’ll find though I haven’t found it yet and the novels I’ll finish writing and the elaborate desserts I’ll actually bake and the little black bikini I’ll finally buy. It seems strange that it’s summer, or maybe it seems strange that it’s summer and I’m still there, in my house, at my table, sitting before an overfilled vase as cars full of people rush to wherever people rush to. In December I lay in a wilted body at the center of a maze of tubes. To raise an arm or a leg took effort. To breathe took effort. On Christmas Eve I pushed myself out of bed, clinging to my IV pole as I maneuvered myself toward a row of regulation chairs at the end of the hospital floor. Through the plate glass windows, far below, a Christmas tree shone in darkness, its needles clothed in a universe of LED lights. I’d like to say I imagined all the kids in their beds trying to fall asleep and all their parents assembling bikes incorrectly and all the other kids in other countries starving inside their skins and the terrible, unpredictable unfairness of the world. I’d like to tell you I wondered about God. But the truth is I wasn’t thinking about anything—just like I’m not thinking about anything as I sit here at my kitchen table six months later. The sunlight falls across the floor in wide squares. The ballerina daisies spill over the top of the vase. The wind streams through the windows and ruffles their ghostly skirts.  Lori Lamothe is the author of three books of poetry, most recently Kirlian Effect (FutureCycle, 2017). Her work has appeared in Blackbird, The Journal, The Literary Review, Painted Bride Quarterly, Verse Daily and elsewhere. My mother told me how her mother wrung the necks of chickens around and around until it was enough. Feathers flew and bodies jerked like fingers before sleep. So hard for me to imagine of her own bird-slender bones, how she rubbed her hands together gently, rocking on the porch and humming some old hymn or other, her dry palms making papery music. My grandfather told me of pre-dawn stillness, then the white-tailed bolt, a shot breaking the quiet. Once I begged to see my first kill when they came back. The buck was strapped to the Ford, eyes fixed wide, head hanging, looking alive but for a drizzle of blood from its slender lip, its body draped on that car like a quilt that doesn't fit the bed no matter how you turn it. My mother told me once her grandfather drowned a litter of kittens in the well. There were too many, his thick hands hard in the water, this economy of letting go. What I wanted was to hold on. I was a child then. The grandparents have gone silently to the ground. ~ Stories don’t always end. They may loosen like skin with age and spill out of shape like words whispered through cupped hands ear to ear. Something about them may gape open like clothes; their seams may give. They may slip around me like borrowed dress-up that drags the floor and catches my heel enough that I pay them mind and don't trip.  Elinor Ann Walker teaches writing online at the University of Maryland-University College. Her poems (also under "Ann Walker Phillips") have appeared in Poet Lore, The Christian Science Monitor, Cicada, Rosebud, Mezzo Cammin, Soundzine, NonBinary Review, and Stone Renga (Village Books Press, 2017) and are forthcoming in Halfway Down the Stairs. She lives in Tennessee with four dogs and her family.  The sky felt quiet. Blue and wide, it was bright, but like a voice underwater, muffled and blurry. Far, far away. Enclosing Mom’s hand in mine, I tucked it into the crook of my arm as we followed the path along the river. I placed my feet carefully, the crunch of gravely sand loud in my ears. The Napa River rolled slowly to our right, a black ribbon tracing its path downstream as we headed up. The water flowed dark, this river Dad had known for eighty-four years. Light filtered through the crooked oak and bay trees, bouncing back off the water, shards of glass shattered on a black tile floor. Vines of plump blackberries twisted around poison oak near the riverbank. The purple berries glistened in the sunlight alongside the blood-red thorns, and I remembered the summer I was fourteen, the wonder of plunging my hands into the immense tangle of blackberry bushes I’d discovered behind Noni’s leaning barn. Dad said they’d been there forever, back when he was a fatherless barefoot ten-year-old, missing school because there was no one else to drive the tractor on the family ranch. He couldn’t see over the steering wheel without standing up. Weary cabins and mobile homes bore silent witness on our left, but Mom and I kept our gaze right, always right, on the river and the cold blackness as it flowed away from us. Soon we would reach the old stone bridge, which Dad and I used to cross when we’d go for a drive along the winding roads tucked into soft green Napa hills, hidden lanes lined with fences made of stone. Weeds grew over the rounded rocks that had toppled out of place. On the riverbank, bushes trembled with the fluttering wings of invisible birds, and I wondered if watercress grew in rivers the way it used to flourish in the creek behind Noni’s prune orchard. On that warm summer evening so long ago, Dad led me and my brother and our border collie through the creekbed, showing us the watercress and explaining that the rounded leaves were edible as salad. We trudged home through the cow pasture, the sweet-smelling grass brushing our pant-legs. Where light shone through the ceiling of trees, bugs as light as air floated in spirals, around and around, in a hurry after things I couldn’t see. A lip of water flapped against the river’s bank, against a rock, then against a fallen tree with a gentle slapping sound. My skin felt the heat, but the sun didn’t warm me. With my mother’s hand pressed against mine in our vacant world, silent, forever-empty now without my father, we followed the path upstream, along the river.  Sue Granzella teaches third grade in Northern California. Her writing has been recognized as Notable in Best American Essays, and she has won numerous prizes in the Soul-Making Keats Literary Competition, a contest for which she is now a judge. Sue has won the Naomi Rodden Essay Award and a Memoirs Ink contest, and her writing has appeared in Full Grown People, Gravel, Ascent, Citron Review, Hippocampus, Crunchable, and Lowestoft Chronicle, among others. More of her writing can be found at www.suegranzella.com There is a small, secret bump on the palm of my right hand that nobody knows about but me. It’s invisible unless you squint, untouchable unless you know what you’re feeling for. I am not sure whether it is a scar or a half-formed pimple or a deformity maintained by a couple persistent skin cells, but it has been there as long as I can remember any part of my body being there. Perhaps even longer. I get the feeling that this is something I should be worried about or ashamed of, but it’s just a tiny bump, and I find myself seeking it out every so often with my thumb--just to make sure it is still there. When I go to the beach nowadays, I spend most of my time on land: scrambling across rocks, peering into tide pools, picking up bits of kelp and threading the rubbery strands through my fingers. I used to be a total water kid. I wanted nothing to do with the sand and sun, instead spending my time bobbing up and down with the motion of the waves and seeing how long I could hold my breath. Now, though, I tend to want to keep dry. So I sit just at the edge of the ocean, on a rock or piece of driftwood, and trace the jagged edges of barnacles still wet from low tide. There’s something familiar about these tiny bursts of roughness that reminds me of a loose tooth, that makes me think of bodies and the parts of me that are not really me at all. Where do you draw the line between foreign and intimate? Do barnacles know that they are separate from the logs that hold them? I would like to think of my body as an ocean. I imagine that would make a lot of things easier--my fear of drowning, my constant staring into the mirror. I would like to touch a palm to my hand and feel the soft curve of myself interrupted by something that cannot exist without me, that cannot be known by anyone else at all.  Ari Koontz is a queer non-binary artist with a degree in creative writing from Western Washington University. In poetry and prose, Ari grapples with identity, truth, and the sheer beauty of the universe, and is particularly fascinated by birds, stars, and other forms of light. You can find more of Ari's work at http://arikoontz.com or follow them on Twitter @paigerailstones  I admit that I used you over the years, to fill with light the cracks where my memory falters. I once read that Penelope didn’t trust a dream in which Odysseus returned to her, because she was uncertain whether the dream had arrived, like true dreams do, through the gate of horn, or—like those from a shadowy district of falsehood—through the gate of ivory. I am like this even now, often wondering whether an incident is truly mine to remember, or, from your vivid retellings, I have stolen it. I am clear in certain things: We sat on the deck in folding chairs then, looking over the valley onto Utah lake, holding glasses of cold tea made with the mint that grew between the rocks in the backyard. When I felt my glass grow slippery in the heat, I would grip it in both of my hands. When we returned inside the house you would count each of the splinters you extracted from my feet as though they were precious—butterflies that could slip away, or more fatally, be crushed inside your fingers. We were endless in those weeks when the Wasatch mountains looked fresh from where we stood and the leaves along the Alpine Loop had not yet turned orange. And yet the nights held a stillness that only a mutual knowledge of impending change could procure. In the sky, Lyra crowned us with her seven stars recognizing one another’s glow: a parallelogram of sorts, and a triangle. Having never for myself pieced them together into anything more than geometry, I resented the stars for which my interpretations, though numinous, though true, could only be discarded. These, and the meteors that refused to show themselves, blue moons which to me, all looked the same. When you pointed to the sky I nodded, not because I understood, but because someone else had long ago understood for me.  Anna-Marie Sprenger is from Provo, Utah and currently studies linguistics at Stanford University. Anna-Marie’s work has appeared in Textploit and Silver Needle Press, and has been presented at the National Undergraduate Literature Conference. |

FLASH GLASS: A MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF FLASH FICTION, PROSE POETRY, & MICRO ESSAYS

Categories

All

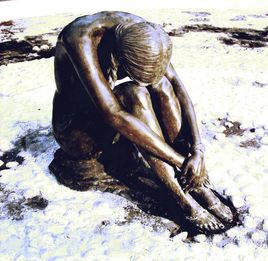

Cover Image: "Verano"

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed