|

I spritz the countertop. I hate grime. John hates spray near his food. “Could you not?” he says, pulling his salsa closer. “Natural and biodegradable are different than ingestible.” I keep my eyes on the rag, scrubbing over the spills. Our kitchen is large, beautiful. John sits at a barstool, three feet from where I’m wiping off residue. No spray has come close to him. “Maybe,” I say. “But this won’t hurt you.” “Prove it.” Then I remember an argument seven years earlier. ~

“Never go to bed angry,” my mom had advised before my wedding. John came in. He held a bottle of Clorox. He stood in front of me. Spritz. I squeezed my eyes shut and pursed my lips. Spritz. I held my hands in front of my face, grimacing, tucking my chin, blotting the droplets. Spritz. “Stop it. I’m listening. Just tell me what you want to say.” “You’re nasty,” John said. “You need to be cleaned.” Spritz. “Leave me the fuck alone!” I yelled, licking my lips. I used my thumbs to wipe across my eyes and cupped my hand to spit into it. I wiped the saliva on my thigh. “You seem angry,” he said, sitting down. “There’s no need to raise your voice.” I tucked my knees to my chest and wrapped my arms around them, burying my head in the space between them while I blinked. I held my breath. “It’s okay,” John said. “You’re just upset. Why don’t we try to talk now?” His hand caressed my back. I shook my head, and John left. I heard water running. My eyes stung. No matter how hard I wiped them, they burned. I made it worse. Wiping. Crying. The faucet turned off. Then I felt it. Cold water poured down my face and neck. My shirt sopped. I shivered. John had dumped a pitcher of water over me. When I looked up, he was on his knees in front of me, his hands on my legs. “Will you talk to me now please?” ~ I look John in the eyes again, lifting the bottle of cleaner and aiming into my mouth. He scoops salsa with a chip. I squeeze the trigger. He is right. It hurts. Not at first, like some things. Later. When you realize what you’ve done. Sarah Mouracade has lived in Anchorage, Alaska for more than a dozen years and intends to stay there. She is completing her MFA in creative writing at the University of Alaska Anchorage, working as the Communications Manager for a local nonprofit, and enjoying every moment she has with her son. Her work has been published in The New York Times, Cirque Journal, Alaska Women Speak, and The Anchorage Press. You can find samples of Sarah’s work at www.sarahmouracade.com.

1 Comment

For Josh In alternating day and night shifts, you work at O’Hare, preparing the albatross. Outside the hangar, the hours choke with exhaust. Wearing, as always, your blue Dickies, you de-ice planes’ wings each winter. How long it lingers—the scent of jet fuel in the fold of your cargo pockets. Last year, once the wind was less cruel and the ice cracked in plates on the surface of the Chicago River, you bought a camera to journal the rites foreshadowing spring. Those late winter weeks wake the same. Salt washing from the sidewalks. The Ferris wheel illuminated in stillness at Navy Pier. The camera brought you awe, burning among the constellations, my brother who never sees the stars. Our father thinks there should be more evenings ending in fireworks, but you’ve seen enough light falling into Lake Michigan. When Delta finally granted you three vacation days, you waited six hours on standby for a seat to LA. The night you walked along Hermosa Beach, a rocket launched—a prisoner’s cinema of blown glass escaping to the sea—its contrail a gash on the horizon hours after you took the photograph. You had searched skyscrapers for beauty; it arrived, beyond the high-rises, sudden and impermanent in a smoke line on the face of the sky. In an ocean that gave itself to fire. Jessica Conley teaches literature at The Steward School in Richmond, Virginia. She is also an MFA Poetry student at Virginia Commonwealth University where she earned her BA in English and MA in Secondary English Education. She has been published in literary magazines such as The Gordian Review and Not Very Quiet. all goldfish while the water washes over. She moves her head from side to side. As if she can catch the rain. My father has taken off again. Strapped a valise to the top of the car. Been gone this time for two weeks now. Mother says things like “he loves me” as if she can it make it true. My brother says things like my father’s a trap, and it would be good for my mother to melt. I say things like we could maybe bring her an umbrella, and these are our parents, you know? In the front yard, tree branches in curls. Floodwaters stitching the street. You don’t remember how awful dad was, my brother says. The women he’d bring home. How they’d sit out front in the car with our father, their blue eyelids, their bobbly heads. How we became dolls whose legs couldn’t move. And so, now, when my father floats his car back up the driveway, and my mother shimmies like a frenzy fish moving towards food, I am not surprised. We will go back to like always. Still, for a flicker, I thought my brother could escape, but instead, he sloshes towards my father, helps him heft the valise off the top of the car, and that’ll make how many times in a row?  Francine Witte is the author of four poetry chapbooks and two flash fiction chapbooks. Her full-length poetry collection, Café Crazy, has recently been published by Kelsay Books. She is a reviewer, blogger, photographer, and a former English teacher. She lives in NYC.  the crunch that came from the yeasty bread fresh out of the oven, crept past the coffee saucer, past the hollow you left in my heart, past the rice all grained up and waiting in the airproof jar, past the soapdish and the dishes in the drainer all twinkly and clean, past the worm waiting inside the counter apples, past the invisible chain of you that is tight around my neck, my finger, my everywhere, past the chip in the bowl that is holding the pear that you bit into, thought was too sour, the way you said we had gone sour, and put it back in its place until you decide if you ever want to give it another try.  Francine Witte is the author of four poetry chapbooks and two flash fiction chapbooks. Her full-length poetry collection, Café Crazy, has recently been published by Kelsay Books. She is areviewer, blogger, photographer, and a former English teacher. She lives in NYC.

Tom Mead is a UK-based author of short fiction. Previous examples of his work have been published by Litro Online, Flash: The International Short-Short Fiction Magazine, Open: A Journal of Arts and Letters as well as various fiction anthologies.

For five dollars, I will hold a tarantula in my mouth, let its hairy legs dangle from the tip of my tongue, tickle the back of my throat. For 10 dollars, I will close my mouth and make the tarantula disappear. I am a wizard. I cannot speak or look you in the eye, so the tarantula is the language I use to trade for your attention. Or maybe I can trade you a dance. My mother taught me how in the living room of our house. The Pointer Sisters on the radio, she would grab my hand and twirl me around and I would climb onto the couch when the sisters asked me if I wanted more and more and more and jump when their voices commanded. Or maybe I can trade you the scar down the left side of my leg. I tried to crawl under my grandfather's fence and caught the bottom of the chain link and it peeled me open. I was too afraid to show anyone because my grandfather liked things to be clean and perfect and unblemished and I still remember what it feels like to be pulled up into the orbit of his anger and hang there while my mother holds my hand and tells me everything is going to be okay, so I mummified my leg instead and hid it beneath my pants. It wasn't until the swelling made it too painful to walk that anyone noticed. I trade in stories. None of this is true. All of it is true. My grandfather kept two tarantulas in his den. They had rose-tipped fur on their abdomens. They felt like stones in your hand when you held them. I slept with them on a green egg crate mattress on the floor. Sometimes, I woke up to them on my chest, their rose-tipped feet feeling in the dark. I would open my mouth to let them squeeze in. I didn't have the language at the time to describe this feeling. Today, I might say it felt like my grandfather's fingers closing around my throat after I peeled the skin off his favorite tree with a garden shovel. In certain light, the scar on my leg looks like a river set ablaze by floating paper lanterns. I have other scars, too, but not all of them you can see, and I also imagine them as estuaries radiating from a center, ablaze in the darkness. A lamp can tell fictions as beautiful as a mouth. These are all experiences you can have and put in your pocket. Mark Zuckerberg encourages me to share everything. When I share everything, I create more meaningful connections with the world. So here is one more. I used to sit on my father's lap, a book between his hands, the book a wall between me and the world. Language poured out of my father's mouth like water. Soaking and wet with language, I would crawl into bed and dream those words onto my ceiling, a crawl of wet soapy words that dripped down the walls and back into me. And this, to me, made my father a wizard. But nothing is left of that world, the twelve-inch space between my father's arms. No matter how much I need to crawl back into the twelve-inch space between my father's arms, no matter how much I try to compress and contort my body, I will not fit. This, this I think I will keep for myself. Kevin Lichty is currently living in Tempe, Arizona with his wife and two daughters. Before that, he lived in Miami, Florida where he was a copy writer for the National YoungArts Foundation; and in Annapolis, Maryland where he was a high school English teacher at a small private school outside Washington, D.C. He was a semi-finalist for the 2017 William Faulkner Wisdom Novel-in-Progress award. His work can be found in Palooka, Four Chambers, Hawaii Pacific Review, and elsewhere.

Woosuk Kim is a sophomore at the International School of Manila. His writing has been previously recognized by the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards, and Zoetic Press.

|

FLASH GLASS: A MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF FLASH FICTION, PROSE POETRY, & MICRO ESSAYS

Categories

All

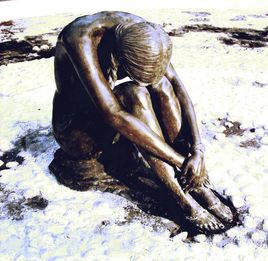

Cover Image: "Verano"

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed