|

Bob and Glenn's Mobil Service Station, St. Louis Talk about your camera lucida, talk about your cave. A man holds a Cadillac over his head, his arms like limbs of an oak, the Caddy a house above, all a tree house, trunk-man and car-house, with a flying red horse sewn to the man's left shirt pocket, Glenn stitched in red threads on his right. And that bikinied woman tattooed in smoke in his right arm, True Love Margaret & Glenn scrolling an inked heart in his left. Glenn steps from under the Cadillac, the Caddy staying put, shifts a lever at the wall. Cadillac descends to the garage floor. And then numerous actual events occur for the first but not the last time--bells ringing for service when car tires roll over the rubber hoses, looking like super-long nightcrawlers, bells ringing for gas, for dipsticks to be eyed, tire pressures to be gauged, windshields to be wiped, several while Glenn wears a dampened red shop towel around his neck, to cool him in the St. Louis summer, so humid the rag does not dry, is more a length of haze about his neck. As he leaves each night Glenn never forgetting to check the payphone for any forgotten coin day's gratuity. Dennis Finnell has published five books of poems. The first, Red Cottage, was awarded the Juniper Prize from the University of Massachusetts Press. His most recent book, Ruins Assembling (Shape & Nature Press, 2014), was nominated for the 2016 Poets' Choice Award. He has taught literature and writing at the University of Tennessee, Mount Holyoke College, and Wesleyan University, and served as Co-Director of Financial Aid at Greenfield Community College for several years. He hails from St. Louis, but has called western Massachusetts home for years.

0 Comments

Last week, the ginkgo tree next to our back door dropped all of its leaves and berries. A late-day sun tumbled to the ground in a million pieces stinking of your room, acrid and rotting. “It itches,” you told me as you dug your fingers into your belly today. The cancer started in your colon. Now the tumor sat at the surface of your skin, lumping your abdomen and oozing. “I want to go outside.” The room hung with your pungent tang, not well masked with cinnamon air fresheners. “But it’s starting to snow,” I told you. It was early this year. “I want to hear the snow.” I smoothed a knitted cap over your partially bald scalp. We walked outside along the back porch, you hanger-thin wrapped in a Harry Potter scarf and grey coat. The spindly trees and your papery body with almost the same silhouettes. Golden ginkgo leaves and berries in mats. Scalloped ice like your half closed eyes. Fluttering snowflakes. “What does the snow sound like?” You stood in the same position with your head tilted, thinking for a long time. I almost repeated my question. “I can hear my heart in my ears and I don’ t feel sick.” I don’t feel sick. Why wasn’t it I feel well? Did you ever forget? Did a lapse trick you temporarily? I scraped up some leaves near the door. Something thudded in the leaf bin when I tipped it to throw the fallen ginkgo inside. A tightly curled chipmunk rested at the bottom. The variegated swipe of symmetric stripes along its back was the only cue that it was more than just a clot of brown leaves. The color of burnt cinnamon pastry. Your hair last year in the sunlight. The smooth-sided bin doomed the animal the second it fell. Poking it with a stick, you exclaimed “It’s alive.” It did not stir. You picked it up like a tiny kitten and cradled it in your hands, stroking its stripes. In one fell swoop, you pitched the chipmunk like a softball to the ground and stomped on it. Crunch. Crick. Crump. Its yellowed teeth stuck out of its now disarticulated and shattered jaw. The furry stripes tangled. Shocked, I stayed quiet. The peace of you was gone, replaced with quiet fury. Had you ever been so callous? “It’s dead,” you declared. “Musta been for a long time. Hard like a rock.” You scratched your belly, then your palms. “I’m burying it.” You chipped away at the ground with your fingers. You scraped the chipmunk pieces into a shallow grave. “I’m done,” you said as you packed the red dirt around. There was dirt under your nails, on your coat. “I heard the snow.” “Me too,” I lied and helped you negotiate the porch stairs. We knotted our elbows together and ambled back inside. Smelling sickness with cinnamon. Mouths of tiny yellow teeth screaming. Yellow ginkgo rotting. I don’t feel sick.  Elisabeth (Lisa) Preston-Hsu is a Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation physician in Atlanta, Georgia. Throughout her medical training and career, Lisa has dabbled in the arts with music, writing, and blogging a years-long stream-of-consciousness love letter to her family at storyofakitchen.com.  I swim through the man’s long hair. After a night of blistering past rocks and a morning of casting waves into the eyes of fishermen, I dance with brunette locks tied by leather. Slink between sunglasses, squint eyes, mix with breath. His wife clicks. I frame the shots with her own spray of split ends, and dive under the collar of her coat, pulled tight against my invasion. I tickle her smile, knowing a fan when I brush against one. Even in the cold, this woman finds my presence to be a blessing; a texture of life. The man does not, but for him, her adoration is enough. I finger the holes in his jacket cuffs, and whistle through the punctured points in the rig he is posing against that predates the term SUV and has seen so many winters that it can no longer hold heat. Everything frays along him and the things he calls his own. Including her. The machine and the man both hold together just long enough to get from one place to the next before coming apart again. He watches his wife. Her grin infects his lips, weighed down at the ends like gull wings just after they’ve muscled through me. The woman is a disciple of mine. A dancing partner always ready to dip and spin. She and her husband have spent years floating just above the waterline, lungs hoping the next wave might not be too much, still burning with the salt of times they couldn’t stay afloat. I swirl the clouds aside to give the couple a moment of sun. A bright photo of their rugged love might fill their sails; might lift them just above the next swell.  Daniel's work has appeared in the Buckman Journal and Chaleur Magazine. He is currently working on a novel and a collection of essays.  My white grandfather uses his narrow hallway to display the work of his granddaughter. The wall acts as a timeline, dating back to my first kindergarten project that is now curling at its edges, yellowing from time. Calendar Contest 2004: won Two young boys face each other with rosy cheeks, and open smiles. They wear corresponding winter jackets with matching mittens. Between them a near complete snowman begins to take form, with coal buttons and branches for arms that look like long stringy fingers. The boy in the green scarf is reaching up high on tip-toes with a carrot in his hand, ready to finish their masterpiece. Their faces aren’t colored in: white as paper. Comic book Contest 2005: won Supergirl is fighting a villain I have since forgotten the name of. They both are midflight, surrounded by puffy clouds. The sun shines as a half circle in the top right corner. Supergirl’s hand are balled into round fists, and her hair blows in the opposite direction of her cape. Her face is neither apricot nor peach: white as paper. Picture book Contest 2006: won A ballerina joins a clown on a boat ride. They pass through twists and turns as they point in amazement at every new exhibit they pass. An enchanted forest with tiny fairies in sparkling dress shine brightly on the third page. All of their faces: white as paper. Self-portrait Contest 2007: lost This is the first time I have colored a face in. My skin: the color of rust. I excitedly overcolor. I am burnt and too dark. The rough construction paper broideries are ripped at the corners, as my grandfather hangs up the wall art without order. But as he takes his guests down the hall, he points at the white faces I’ve drawn: stamped with 1st place ribbons. He tells them how he passed on his artistic gene, how we spent many afternoons doodling in a sketch pad together. He tells them nothing of the way he would erase the penciled shadings of my characters faces until they were once more as white as paper. And now they all hang, as if it’s a collage of evidence, a wall for him to point to and say, look at what I’ve taught her. Vanessa Zimmerman is a poet currently residing in Ithaca New York. More of Zimmerman’s work can be found in The Merrimack Review, Sagebrush Review, Slipstream Press, The Healing Muse, Literature Today, and Serendipity magazine.

I noticed her heel-click-hip-twist hourglass silhouette as we walked toward bright light at the end of a long corridor between Terminal B and Terminal C. My husband, teenage son, and all the other travelers flowed past on the electric walkway: She and I the only ones who'd chosen to move on our own locomotion. She clicked along a good twenty feet ahead of me, blonde hair in a chignon, a few locks flying loose around her face. She trod with long-strided purpose. But her heels could not outpace my flats. I caught up, though I did not overtake her. That's when I noticed the zipper pull on the back of her uniform: a little silver plane-shaped pendant hanging three or four inches from the top of the zipper on a blue jeweled chain. Did the dress come that way? I asked. No, she said. I like it. Thanks, she said. She smiled with dimples. I blushed. The winged pin on her chest, which I'd hoped would say her name, said, "The Netherlands." I'd never been. So many places I’d been... But not there. I slowed my stride to match hers. She noticed me noticing. You should come, she said. We both walked more slowly. She brushed the inside of my palm with her fingertips. I should, I said, blushing harder. My men hailed me from the end of the hall like a pair of foregone conclusions: I hurried to rejoin them. I didn't know then we'd be on the same flight; where she would serve me water and champagne, coq au vin, strawberry tarts, honeydew like a plate of crescent moons, and for breakfast an omelet and rose-petal tea; where my men would sleep, one row up, snoring, farting, oblivious; where I'd spend the eight and a half hours between Paris and Boston awake, dreaming of pulling her zipper; where she would offer, in the dark, on her break, somewhere over the Atlantic, to “tuck me in”; and where I would, foolishly, decline.  Jennifer Companik holds an M.A. from Northwestern University and is a fiction editor at TriQuarterly. Her accomplishments include: Pushcart Prize Nominee, Border Crossing; first prize, The Ledge’s 2014 Fiction Awards; and work appearing or forthcoming in: Adanna, Muse, and Northern Virginia Review. By reading her work you are participating in one of her wildest dreams.  Somewhere after Dog Island but before the Leadbetter Narrows, there was a gust of wind that caught me dozing off a hangover and pulled our only chart right out of my hands. Like a pair of cotton shorts on a clothesline can be given shape by the breeze—as if it’s trying them on—the wind had a go with our chart, spreading it out flat, then pushing it out like a ghost under the boom and over the toe-rail into the bay. Will laughed—a single very-high note made through closed lips, a small remnant of how I remember him being when we were younger, when he was a little pudgy and chaotic. Now he was twenty-three, thin, and with a dark, short, and well-kept beard that covered much of his face, even his cheekbones. You wouldn’t expect that sound from him unless you were a friend, in which case it was most welcome, and a sign that all was well and joyous with the world. “It’s waterproof,” he said, letting the mainsheet run out between his fingers, preparing to come about, always gentle and methodical now in the adult iteration of himself, as if he knew—like a postal driver who doesn’t take left turns—that the rush inevitably slows you down. He pushed the tiller over, the bow pointed up light and responsive into the wind, then through it. I let the jib backwind and then snapped it over; the sails loaded and pulled, and we climbed to the windward side, flattening the small boat and accelerating out of the tack as if we’d rehearsed it. “There it is,” he said, pointing just downwind, two boat-lengths away. “We’ll loop around. Make it a proper figure-8 rescue.” I nodded, but just then a small swell washed over the chart, flooding and filling whatever parts of it there were to fill. Then it was gone, and I was gone after it—over the back rail in my clothes and sunglasses—my arms outstretched to soften the slap of the water against my aching forehead, and behind me through the air Will just sat at the tiller, beaming and pounding the deck and laughing his little laugh, because it was summer and all was well. Robin Lewis graduated from Colby College in 2017 with a degree in Environmental Policy. He likes boats, job sites, succulents, and vacuuming his room. He also likes Maine, where he's from. He currently lives and works as a carpenter in Burlington, Vermont.

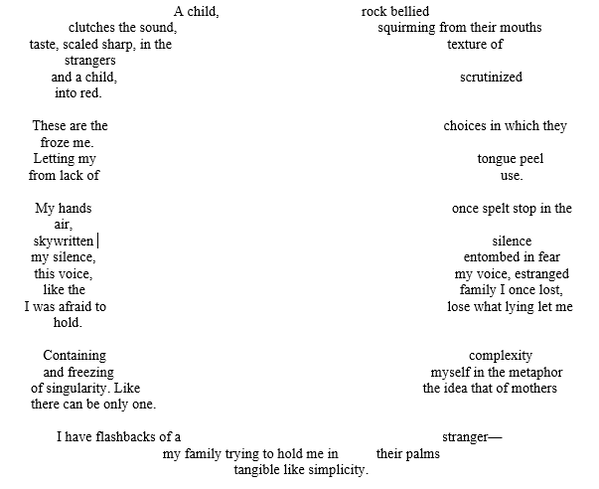

Cori Bratby-Rudd is a queer LA-based writer. She graduated Cum Laude from UCLA’s Gender Studies department, and is a current MFA Candidate in Creative Writing at California Institute of the Arts. Cori enjoys incorporating themes of emotional healing and social justice into her works. She has been published in Ms. Magazine, The Gordian Review, Califragile, and PANK Magazine, among others. She recently won the Editorial Choice Award for her research paper in Audeamus Academic Journal and was nominated as one of Lambda Literary's 2018 Emerging Writers.

|

FLASH GLASS: A MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF FLASH FICTION, PROSE POETRY, & MICRO ESSAYSCategories

All

Cover Image: "A Peaceful Coexistence Part II"

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed