|

I. Atoms and words combine themselves into complex structures: molecules and sentences, poems and beings. These pieces hold a limited amount of meaning alone, but it is only through the interconnected relationships of these base elements that they can ever become alive. To break apart these structures is to kneel before a pile of discrete pieces of information. A cell is defined by its purpose for the body as a whole, a word by the body of work. There is value in the syntax, the order, the configuration. Rearrange the elements and the whole thing may fall apart. II. Language evolves. As time goes on, a combination of sounds mutates into something that doesn’t resemble itself anymore. Every time a sequence is copied, it brings the threat (or blessing) of alteration. Without this swerve, every product created by nature or poet would be a mere copy of the original. III. A good poem already exists. The writer can imitate it, ensuring that she never rises above her predecessors and lives her life a parrot. She can rebel against it, at the risk of estranging her readers and defining her work by spite. Or she can take that work and distort it slightly, expand the boundaries to her advantage, test the limits without going too far off the edge. Nature works the same way; she is a fine poet. IV. Poems adapt to the fitness of their environment. As language evolves, the values of art must shift as well, else they will become extinct due to the meager supply of fitting words. The ideal poetic line is a genome, manipulated by entropy until an infinite series of variables miraculously synchronize with its surroundings, and it thrives. It’s hard to watch old words die. They don’t represent the language of the listeners anymore, but they preserve the language of the writers. Leave them behind when history turns its page. They will be fine. V. Poetry is a ring species. It is tempting to categorize history into eras. A segment of time is defined by one concept, and then in one single strike of the clock is defined by another. The division of history into Renaissance and Shakespearean and Romantic erases the links in between that hold them together. Change is a gradual process. The process isn’t over yet. Every individual moment is an era, defined by itself. VI. Think about the music of the spheres. The universal symphony is never over; as one tune ends, an elided cadence begins a new melody, recombining the same notes into an impossible number of variations. The last line of one poem is the opening to another. As long as art continues, it can’t really fail; even a poor piece of writing or a mislaid tune may serve as inspiration for the next. The only mistake is to stop creating. Everything finds its natural place in the end.  Audrey Dubois is a Rhode Island poet and creative writing graduate student at Emerson College. She likes weird antiques, frozen yogurt, and PBS documentaries about Karen Carpenter. You can find her on social media as @platypusinplaid

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

FLASH GLASS: A MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF FLASH FICTION, PROSE POETRY, & MICRO ESSAYSCategories

All

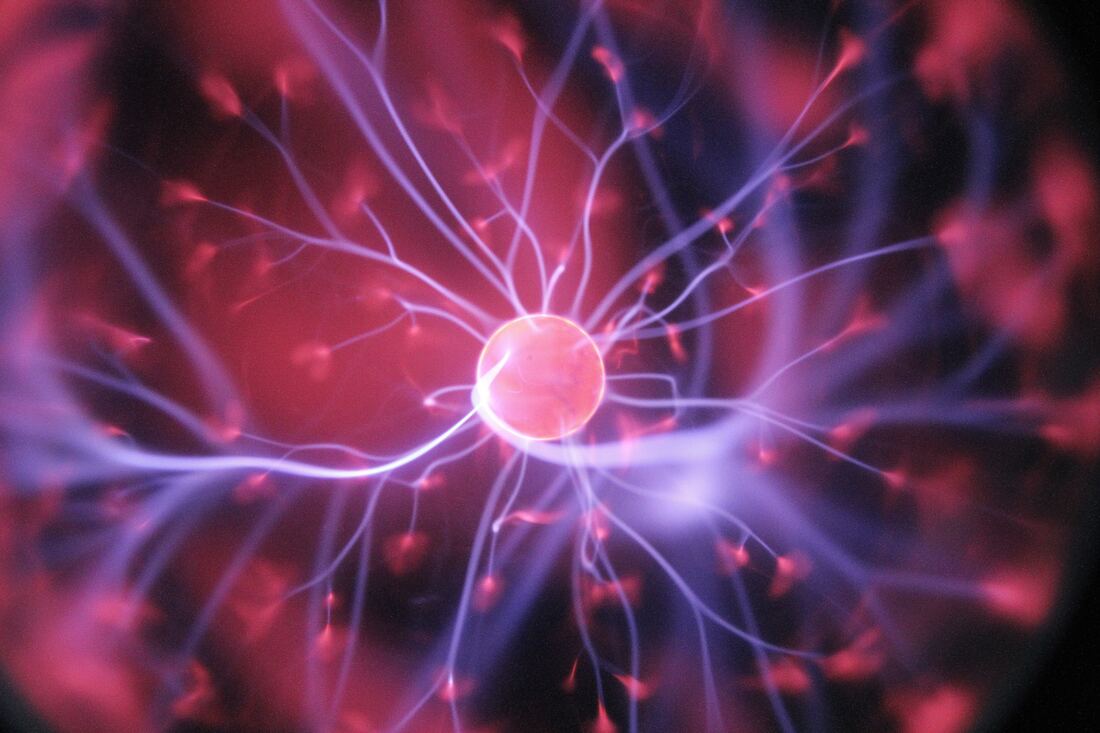

Cover Image: "A Peaceful Coexistence Part II"

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed