|

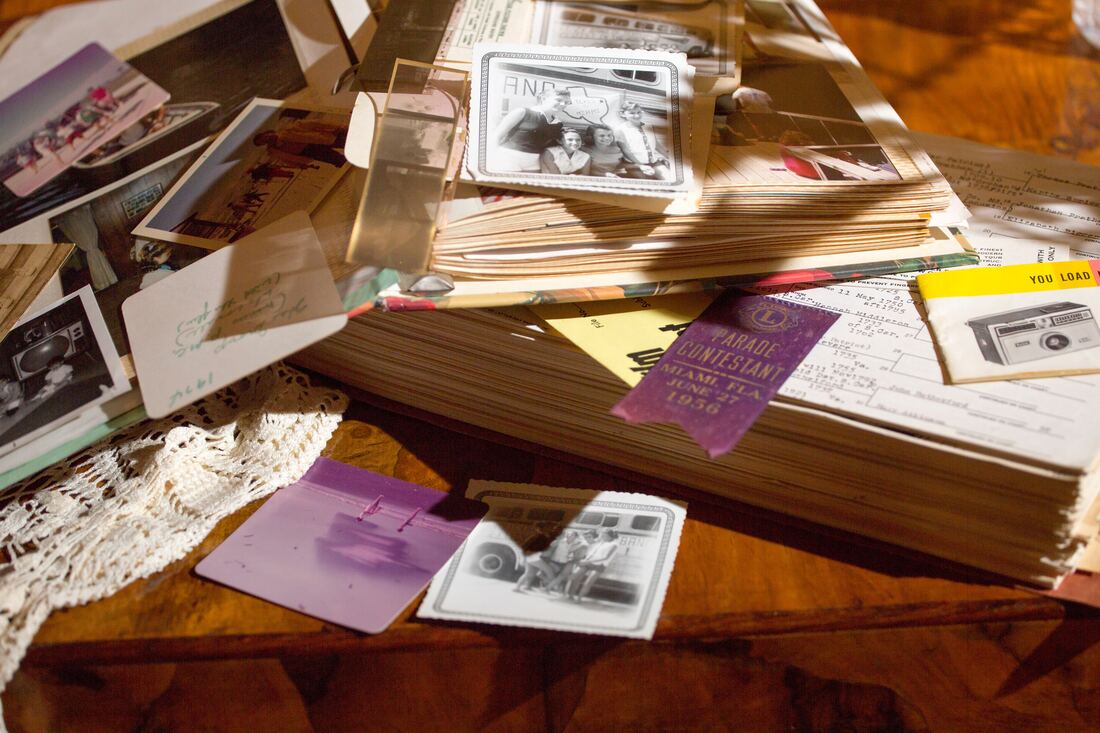

On my birth announcement, my mother wrote my full name in green ink next to a black and white infant photo of my disembodied head. My two middle names are those of my maternal and paternal grandmothers, since my parents did not want to choose one and offend the other. At the bottom of the announcement, my mother has written “She is a doll!” I’m in the process of remaking my baby book. Sometime in the 1980s, my mother collected all the old family photos she had and distributed them into adhesive albums representing each of my brothers’ and my respective childhoods. By the late 1990s, “scrapbooking” had become a verb in the English lexicon. Craft stores exploded with scrapbook supplies, and it was announced that everybody’s old picture albums with the sticky-back pages were slowly poisoning our family photos. Our matte and glossy prints needed to be rescued from these toxic books and preserved in acid-free, lignin-free environments before the images disappeared completely! My baby book is one such time bomb. As I use a piece of dental floss to carefully extricate the photos from the book to remount them in an archival safe album, I’m getting increasingly irritated at my deceased mom for her practice of closely cropping the photos around the people. The book is full of imperfect circular photos and little people-shaped cutouts, leaving unseen any possible contextual information in the background that might create a fuller picture of my life, such as a house we lived in or an exterior landscape. She wrote notes in the margins such as “In the house on the golf course” or “On a trip to Lake Powell,” but I question the usefulness of any of those identifiers without the visuals that would have given them meaning. It’s frustrating to try to reconstruct my own history when I can just see the corner of a sofa or the toes of someone’s foot next to me, toddler-sized, on the floor. I want to be grateful to my mother just for making the baby book. I should be content to have these photos of me at different ages, some including her, my brothers, and our pets. As far as I know, there is only one photo that was ever taken of my entire nuclear family, and thank goodness, she has not cropped that. It is a 2x3 color print of me in a baby stroller with my brothers squatting on either side of me, and my mother and father are standing behind me with their hands on the stroller. My mother is looking at the camera, my father and my brothers are looking at me, and I am looking at my oldest brother, who is making me smile. It appears to be a casual, pleasant family moment. I have no memory of my father, who died when I was a baby, so images and stories are all I have to go on. My mother always painted a rosy picture of him as I was growing up, and it would be many years before I would learn that what was going on in our lives was anything but harmonious. Apparently, my father’s sister knew there was discord between my parents, but she loved them both and chose not to take sides when they battled. When I asked my aunt for more of the details that had always been muddied for me, she said in her slow and gentle way, “Sometimes two people just aren’t meant to be together, you know? What’s important is that we remember the good, and with a breath of kindness, we blow the rest away.” I can see in the picture now that my mother and brothers seem to form a protective triangle around my stroller, while my father is off to the side, just one hand on the handle. If my mother had cropped this photo, it’s possible only his hand would be left. Perhaps her penchant for cutting out the backgrounds of photos was her breath of kindness, erasing any visual cues that would tattle on the pain. By cropping and saving the people, she was choosing to keep the focus on the good. Probably she was just trying to fit more photos on the page.

1 Comment

Photo by Joan Oger on Unsplash Photo by Joan Oger on Unsplash The spring nestles beneath old shade trees that edge a farm field. It’s a remote location, but for decades, locals have been parking in the dirt turnoff and filling jugs with the cold, fresh water that runs out of a single pipe and into a shallow stream crowded with daylilies. Our family camp has no plumbing, so every couple of days during vacation, we drive to the spring. When it was my turn to make a water run, I made my teenage son, Sean, come along. Sean had grown over the last year, passing the six foot mark, but he was still the same quiet, gentle kid he’d always been. He brought his Rubik’s cube, and the clicking sound filled the car. Sean’s not much of a talker. When Sean and I pulled up, a car was already parked beside the spring. An elderly woman stood at the back of her car with several plastic gallons of water at her feet. She fumbled with her keys as she opened her trunk. “Go help her,” I said to Sean. He didn't look up from his Rubik's cube, but he nodded. I yanked the crate of empty jugs from the trunk, set them on the ground, and bent down to pick up the loose caps that had fallen. The car door slammed as Sean got out. I glanced up at the sound, and the woman turned. Even from my awkward position, crouched on the ground behind the car, I could see her face. She looked terrified. I looked behind me. A narrow road wound uphill through fields of timothy and daisies, a few roadside trees splashing shade onto the pavement. Cows in a far field chewed contentedly in the sunshine. But the woman wasn’t looking at the farm fields. Her eyes, wide and frightened, were on my son as he walked towards her. Sean’s long dark hair was pulled back with a ragged bandana above scruffy facial hair. He wore a black t-shirt and black pants, neither of which had been washed since we arrived at camp. Sean isn’t a smiley person; even when he was a child, he always looked serious. He is tall and strong, and—I realized suddenly—fairly intimidating. In a flash, I saw the elderly woman's perspective. My sweet, gentle son—the kid who had never even been in a fist fight, who never went fishing because he didn’t like killing things, who helped classmates with their math homework—looked to her like a threat, a menace, a danger. Quickly, I stood up, so that the woman could see me. At the same time, Sean stopped walking and said in his shy way: “Do you need some help?” Relief spread across the woman’s face. Sean lifted the jugs of water, one at a time, and put them gently into her car. The woman, still flustered, said thank you, and she drove away. Sean carried our crate of water jugs over to the pipe that gushed spring water. He picked up an empty jug, rinsed it, and held it under the water. “That woman was afraid of you,” I said. He shrugged. “I get that a lot.” He spoke so softly that I could barely hear his words above the gurgling water. His hair hung into his face as he screwed the top onto the water jug and reached to grab the next empty one. “I hate the stereotypes people have about teenage guys,” I said, loudly. Sean looked up, shaking his hair out of his face. “It's worse for women," he said. "Because they have legit reasons to be scared."  Janine DeBaise has published in essays in numerous magazines, including Orion Magazine, Southwest Review, and The Hopper. Her poetry includes the book Body Language and the chapbook Of a Feather. Her academic writing focuses on environmental and feminist issues. She teaches writing and literature at SUNY ESF in Syracuse, New York. You can find her at www.JanineDeBaise.com My grandson Ben took on the role of healer early on. At 18 months, he saw Daddy fall, turn purple, and briefly die of a v-fib. After Daddy came home from the hospital, Ben regularly took daddy’s blood pressure, listened to his heart, and measured his oxygen saturation. As he became more aware of the imminence of death, Ben became more alchemist/healer than doctor. At four, he had invented reincarnation. At our first get-together, as part of the gradual lifting of restrictions, almost six-year-old Ben told me he had the power to make me young again. He placed his hands on the back of my neck, sang some healing words, and told me, “In three days, you’ll wake up younger." Before seeing Ben again, I got my pandemic hair axed and mowed my beard. When we saw Ben again two weeks later, he looked at me wide-eyed and said, “It worked.” He then started a round-robin conversation about what animals we would each like to come back as in our next lives. Mommy picked a giant tortoise because they live longest. Grammy said a whale. I said I’d spin the wheel. Ben said he plans to be human next time, too. The next afternoon, six of us—Ben and his twin Bella; four-and-a-half-year-old Mikey; Mommy and Daddy; and me Papa with my walking sticks of us—drove to the C&O Canal towpath for a walk. Grammy stayed home, tuckered out from Ben’s efforts to make her young again. The towpath’s surface consisted of small gray stones with mixed-in shell fragments—nearly ideal. Almost immediately, Mikey tore ahead. Mommy laughed, “At least I know where he’s going to be when he stops.” Mikey’s feet ran out from under him. He began crying when he hit the ground. We sped up to see whether he was hurt. Mikey had skinned a knee and there were hints of blood. Mommy picked up Mikey to console him. Ben stepped toward Mommy, placed his cupped hands over Mikey’s knee, and began singing, “Heal up Mikey, heal up Mikey” to the tune of “Tender Shepherd.” Mikey quickly quieted. Ben removed his hands, inspected Mikey’s scrape, and exclaimed, “It stopped bleeding!” Mommy sat Mikey on her shoulders but when he couldn’t sit still, put him back down. No sooner had Mommy put Mikey down than Bella tore ahead with Mikey close behind. As Bella turned to see how far behind Mikey was—a no-no for runners—she tripped and fell. She too had skinned her knee. After inspecting the scene, Ben cupped hands over Bella’s knee and began singing, “Heal up Bella, heal up Bella,” again to the tune of “Tender Shepherd.” Bella rapidly quieted. Nevertheless, Daddy picked up Bella and carried her on his shoulders. When we reached the water pump, Bella wanted down, and Daddy cooperated. Ben pumped consistently until water came. Everyone splashed in it and drank their fill from their cupped hands. We walked the rest of the way to the tunnel. To quash plans in the making, Mommy read aloud a sign, “Do not climb on the stairways on both sides of the tunnel entrance because they get slippery.” The tunnel had no lighting, but it was a bright day, so we could see using the diminishing light behind us. And, at the far end, roughly a mile away, we could see the light at the end of the tunnel. Because the ground surface was uneven, there were inevitable puddles. We turned back when Mommy felt unsafe going further without flashlights. Mikey had already taken off his puddle-wet shoes and socks. Once we reached broad daylight, Mikey began barefooting the towpath while availing himself of every puddle. Bella whimpered, so Daddy restored her position behind his neck. Mikey stopped and complained he hurt his left foot. Mommy found a blister on Mikey’s heel and put him back on her shoulders. I accidentally planted my left walking stick in front of Ben. He didn’t notice, tripped, went down hard, skinned a knee and elbow, and began to cry. Mommy put Mikey down. I said, “Ben, remember, you can heal yourself.” Sitting on the ground, Ben cupped hands over his knee, singing “Heal up Ben, heal up Ben” to the tune of “Tender Shepherd,” stretching “Ben” into two syllables, without tears. Mommy said, “If you’d like, Ben, I can carry you.” Ben shook his head, “Mommy, I got this.”

|

FLASH GLASS: A MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF FLASH FICTION, PROSE POETRY, & MICRO ESSAYSCOVER IMAGE:

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed