|

We are pleased to present our annual flashglass anthology! Comprised of all flash works originally published online at rowanglassworks.org in 2023, this anthology is available for online viewing and for purchase in print.

By Glassworks Magazine in flashglass 36 pages, published 12/30/2023

an anthology of work originally published at rowanglassworks.org

0 Comments

I want to know what love is. There’s a place within me where sun grasses grow from damp wood, a small pocket of sunlight at the bottom of a marsh. I wander through sticky things, fluffy things floating around me in the heavy heat—dandelion seedlings, spider web threads, translucent wings flashing indigo, and monarchs fluttering low to the ground in search of fruity milkweed. But there’s also nightcrawlers burnt to a crisp. And poison hemlock clutching the shadows. And goldenrod being choked out by the guard rail. I step around smashed glass on the side of the road glinting like emeralds. I almost want to touch it, lick away the blood. The muggy air becomes laced with exhaust from a passing truck that pulls over to the side of this hometown road. The wind picks up. The air turns cooler. And a dark storm cloud inches its way across the sun, blotting out the heat, however briefly. I eye the truck, lingering by the curb. All I know is what love is not: a black snake, up ahead, coiled in silence.  Jenn Powers is a writer and artist born and raised in the woodsy hills of northeastern Connecticut. Her fields of study are creative writing, Gothic literature, and nature/environmental writing. She's a self-taught visual artist and photographer, which she's been involved with since she was a child in the '80s and '90s. Her work has been anthologized with Kasva Press (Israel), Running Wild Press (Los Angeles), and Scribes Valley Publishing (Tennessee), and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and Best Small Fictions. The lake was always still on Sundays. Almost like God had commanded it, just in time for his baptisms (or so my father would say.) I didn’t like to watch. The Church left a bad taste in my mouth, even then. The grape juice stained my teeth, and the cracker felt stuck in my throat. I choked it down like I would the hymns I sang with my sisters. “How great is our God, sing to me how great is our God.” (In my experience, never that great.) The girl that day was tall and blonde and ready to be ruined. She didn’t know it yet, but she would be. Her white dress trailed the sand by the lake; I could see sand clinging to the hem, her ankles, working its way between her toes. My father led her there. He led all of them there. I wanted to scream or shout, but I left my voice behind in the pews. Instead, I stood there quietly. I didn’t like to watch, but I did. Someone had to. The girl smiled. She had the look of a lamb unknowingly climbing into a lion’s mouth. My father guided her into the lake. I imagined his hands felt like battery acid. She didn’t know. They never knew. He gently dragged her in, shoulders first. He pushed her down until she was in the lake up to her neck. Then, slowly, joyously, he shoved her face underneath. He didn’t stop until she was still. No one had ever survived a baptism.

I’m out walking and crying for my friend’s loss and about how hard it was for her to watch her sister slowly disappear, and how the last time I saw my friend, when we had dinner in New York with industrial chic tables and large glasses of wine, she said, we treat animals better than we treat the dying, and all I think about is death: when I wake up, when I fall asleep, when I’m working, and I know what she means and I cry for myself and for all the losses around me, and the people driving by must wonder what’s wrong with me, if they look up from their own problems—and why should they?—and I turn into Lakota Oaks, the conference center that’s going to be a school but used to be a monastery, and you can see the monks’ graveyard at the top of the hill from the long beautiful pond around which I now walk the remaining stations of the cross, an unbeliever amidst the incomprehensible universe, and I think: the universe is big enough to hold my grief without getting hurt itself. I don’t have to carry it all, and the man who was running the trail in the opposite direction passes me again, saying, beautiful day, and it almost is.

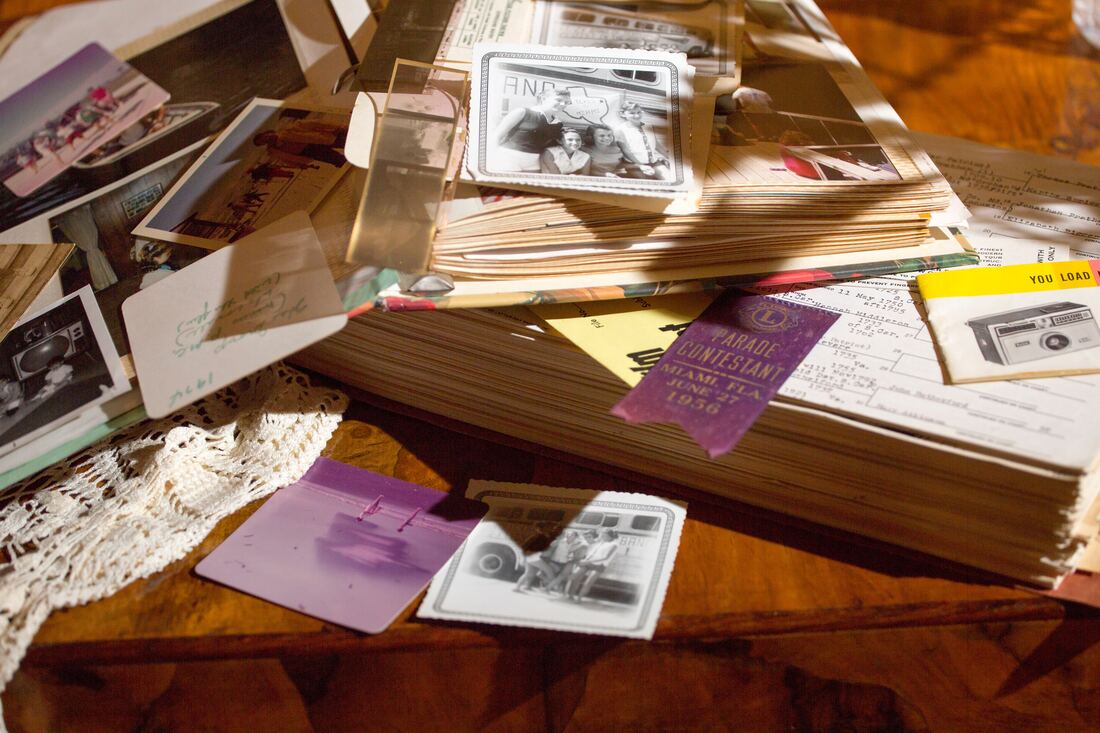

On my birth announcement, my mother wrote my full name in green ink next to a black and white infant photo of my disembodied head. My two middle names are those of my maternal and paternal grandmothers, since my parents did not want to choose one and offend the other. At the bottom of the announcement, my mother has written “She is a doll!” I’m in the process of remaking my baby book. Sometime in the 1980s, my mother collected all the old family photos she had and distributed them into adhesive albums representing each of my brothers’ and my respective childhoods. By the late 1990s, “scrapbooking” had become a verb in the English lexicon. Craft stores exploded with scrapbook supplies, and it was announced that everybody’s old picture albums with the sticky-back pages were slowly poisoning our family photos. Our matte and glossy prints needed to be rescued from these toxic books and preserved in acid-free, lignin-free environments before the images disappeared completely! My baby book is one such time bomb. As I use a piece of dental floss to carefully extricate the photos from the book to remount them in an archival safe album, I’m getting increasingly irritated at my deceased mom for her practice of closely cropping the photos around the people. The book is full of imperfect circular photos and little people-shaped cutouts, leaving unseen any possible contextual information in the background that might create a fuller picture of my life, such as a house we lived in or an exterior landscape. She wrote notes in the margins such as “In the house on the golf course” or “On a trip to Lake Powell,” but I question the usefulness of any of those identifiers without the visuals that would have given them meaning. It’s frustrating to try to reconstruct my own history when I can just see the corner of a sofa or the toes of someone’s foot next to me, toddler-sized, on the floor. I want to be grateful to my mother just for making the baby book. I should be content to have these photos of me at different ages, some including her, my brothers, and our pets. As far as I know, there is only one photo that was ever taken of my entire nuclear family, and thank goodness, she has not cropped that. It is a 2x3 color print of me in a baby stroller with my brothers squatting on either side of me, and my mother and father are standing behind me with their hands on the stroller. My mother is looking at the camera, my father and my brothers are looking at me, and I am looking at my oldest brother, who is making me smile. It appears to be a casual, pleasant family moment. I have no memory of my father, who died when I was a baby, so images and stories are all I have to go on. My mother always painted a rosy picture of him as I was growing up, and it would be many years before I would learn that what was going on in our lives was anything but harmonious. Apparently, my father’s sister knew there was discord between my parents, but she loved them both and chose not to take sides when they battled. When I asked my aunt for more of the details that had always been muddied for me, she said in her slow and gentle way, “Sometimes two people just aren’t meant to be together, you know? What’s important is that we remember the good, and with a breath of kindness, we blow the rest away.” I can see in the picture now that my mother and brothers seem to form a protective triangle around my stroller, while my father is off to the side, just one hand on the handle. If my mother had cropped this photo, it’s possible only his hand would be left. Perhaps her penchant for cutting out the backgrounds of photos was her breath of kindness, erasing any visual cues that would tattle on the pain. By cropping and saving the people, she was choosing to keep the focus on the good. Probably she was just trying to fit more photos on the page.

She walks down the road, numb, oblivious to the rasp of burnt grass against her skin. Who knows what happened at the old farmhouse far behind her, its windows like black eyes, watching her walk away? It could be a home she is walking away from, full of loving parents, family members who meant well but just didn’t understand her dreams, could be something worse, a childhood home, but full of dark memories that were all too easy to leave behind, could be a stranger’s house, some place she woke up in, abandoned in a basement or tied to a radiator, her captor off on errands for just long enough to craft an escape, it could be even worse: her own home, her husband, dead on the floor, either because she did something or something happened to him, a heart attack, a hammer to the back of his skull, an accidental fall down the stairs, a push. Is that blood on the hem of her calico knee-length dress, the thin cotton fabric catching and trapping the dried burrheads as she walks? Is that a knife in her hand, used to cut herself free from ropes with agonizingly slow and careful determination, used to strike out at her captor, her husband, her lover, with unexpected fury and force? Or is that just her purse, clenched tightly against her side, containing a single bus ticket with an unreadable destination, a handful of bills, a phone number and address scribbled on a wrinkled scrap of paper? Holly Day’s writing has recently appeared in Analog SF, The Hong Kong Review, and Appalachian Journal. She currently teaches classes at The Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis and Hugo House in Seattle.

“Literary Mimesis; or Plagiarism Pays.” Karen Craft. Product Description: It’s only cheating if you get caught. We’ve never been caught. What we do is you. We do your style. You send us sample copies of papers you have actually written in the past. (We require a minimum of 5 papers and two weeks to plan our approach). Ideally, please and thank you, send us your packet four to six weeks in advance of your essay’s due date, adjusting accordingly for difficulty and length requirements. We charge 0.09 USD per word ($450 for a 5,000w. paper). Our employees are frustrated, MFA holding novelists sick of rejection on the open market who’ve made a nice living for themselves in this peculiar industry catering to lower-level undergraduates— those from money/of money/with money (to burn) at elite public and private American universities. These people, our “fixers,” possess an uncanny ability to sound like you, fast, getting you the grade you need while saving you valuable party time that would otherwise be wasted in writing papers. We scrupulously avoid even the hint of foul play, hiding all misbehavior from schoolmarmish professors. Disclaimer: We do not guarantee good grades, only authenticity. If you’re a D student, we will make you sound like a D student. We save you time writing papers you don’t want to write, WE ARE NOT MIRACLE WORKERS. Plus, consider, lowkey and just straight up FR: if you are a D student and we turn in an A paper for you that kind of, like, um, ya know, defeats the whole purpose of our service. It’s like some scumbag election fraud specialist who deserves all he gets in terms of fines and punishments and punitive reparatory measures measured out to the final inch and centimeter deciding to stuff six hundred fake ballots in one mailbox as if the people picking up the early voting would take this and nod, ‘sounds good, looks like 600 voters do live at this address.’ Idiot. We are not idiots. Here’s a two-pronged, AB sample from one of our best, ‘007,’ writing for the aforementioned D student on the following topic: The Secession Crisis during the American Civil War. Look and see for yourself how effortlessly 007 is able to sound like a student who barely passes via two distinct styles: first, the classic jackass frat moron and, in the B sample, the over-eager virtue signaling present-imprisoned speech puritan. *Option C included for the rarely ordered but elite-pricing ‘true F’ paper.

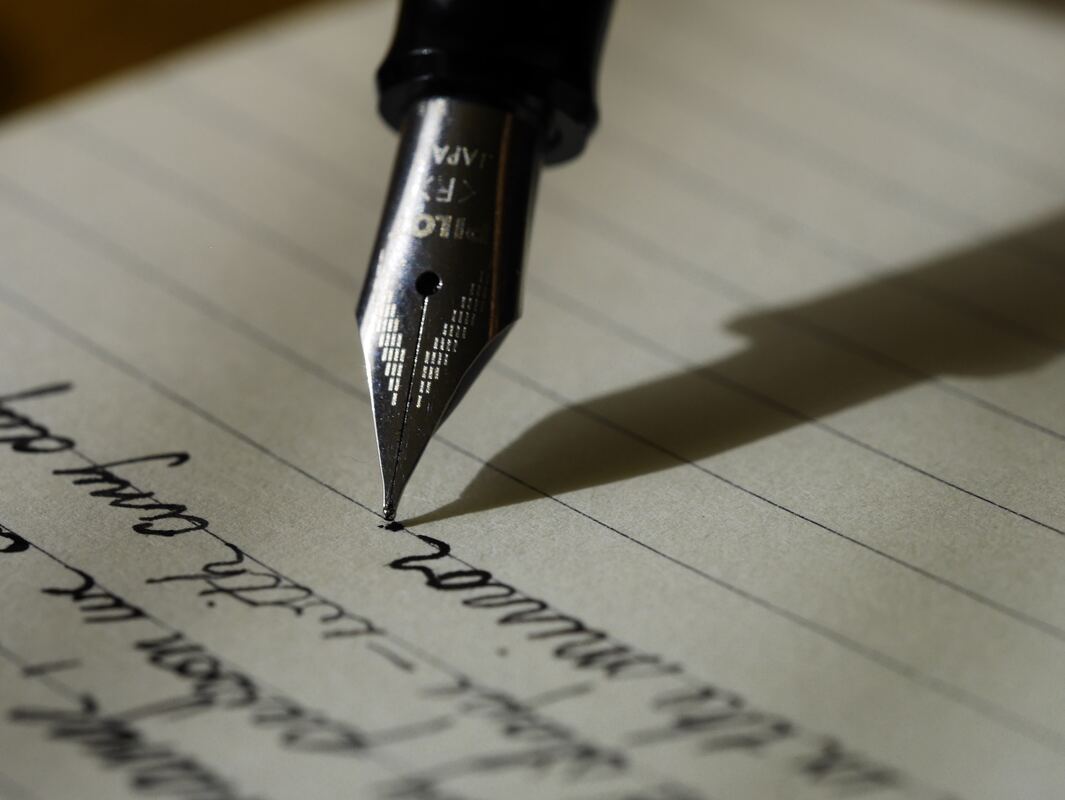

Photo by Sacha Verheij on Unsplash Photo by Sacha Verheij on Unsplash You turn away from the screen. You half-shrug. Time for a cliché to cut the tension, guaranteed to make everyone grunt and shake their heads in pseudo-profound melancholy. This has happened before, you begin, it will happen again. Suddenly she’s shaking your arm, yelling at you to shut up. Who cares about before, who cares about again? She screams. It’s happening to my sister, damn you. It’s happening right now. Everyone squirms. Everyone glares at you, as though you had flown the plane, had pulled the trigger, had dropped the bomb that pulverised her sister’s neighbourhood in a land far enough away that no one really cares, even when - well, even now. All over the world, someone is shaking a sputtering stranger, screaming, it’s happening to my sister, damn you. It’s happening right now.  Hibah Shabkhez is a writer of the half-yo literary tradition, an erratic language-learning enthusiast, and a happily eccentric blogger from Lahore, Pakistan. Her work has previously appeared in Black Bough, Zin Daily, London Grip, The Madrigal, Acropolis Journal, Lucent Dreaming, and a number of other literary magazines. Studying life, languages, and literature from a comparative perspective across linguistic and cultural boundaries holds a particular fascination for her. https://linktr.ee/HibahShabkhez Here are the fuming chairs of a round table made rectangular by gilt-edged name-plates. Here is the world that promises sanctuary to strangers like me, that promises to live and die by the truth. Here are the words that arrest you, first when this world makes that promise and then when it breaks that promise. Here is a pen, announcing and denouncing things, until the fingers holding it are twisted in the darkness by shadows with muffled footfalls. The pen is your pen, the fingers are your fingers, but you cannot / will not / must not tell the story thus; so you say instead: here is the pen that ... The pen stops, hovers over a blot for one flicker of the guttering candle, then rises and moves away from the page. A massacre vanishes from history.  Hibah Shabkhez is a writer of the half-yo literary tradition, an erratic language-learning enthusiast, and a happily eccentric blogger from Lahore, Pakistan. Her work has previously appeared in Black Bough, Zin Daily, London Grip, The Madrigal, Acropolis Journal, Lucent Dreaming, and a number of other literary magazines. Studying life, languages, and literature from a comparative perspective across linguistic and cultural boundaries holds a particular fascination for her. https://linktr.ee/HibahShabkhez it is summer 2022. we have ipads and airpods, watches that can detect your breathing and health, call 911 when you fall. dogs communicate with buttons, colorful pills take your pain away, boxes light up with loved ones miles away. it is 2022 my grandmother tells me she had more rights than i do. than i will now. she says it’ll be like before and denounces the men that made this happen. it is 2022 and some people tell me i’m silly for saying i don’t want a bunch of mini mes running around and i ask them where will they run? with a recession coming down the street and a mother who picked teaching, inflation too high for raises to meet, where will the children i am told must come out of me, run? besides their school with code reds, lockdowns and intruders carrying military grade weapons to use against their bodies, i notice no body is safe and i ask where will they run? it is 2022 and my grandmother jokes about returning to her home country. she says she had more rights than me.  Crysta Garcia is a teaching artist born, raised, and based in New York City. As an educator, she has had the pleasure of working with Community Word Project, the Aspen Institute, WriteOn NYC, and other organizations that provide arts education to various school programs. She is a 2022 graduate of The New School’s Creative Writing Program, and now holds her MFA in poetry. |

FLASH GLASS: A MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF FLASH FICTION, PROSE POETRY, & MICRO ESSAYSCOVER IMAGE:

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed