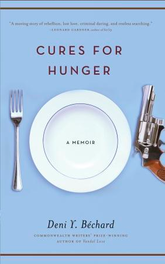

In Deni Y. Béchard’s memoir Cures for Hunger, the reader is introduced to the author as a young boy enamored with his father. The author’s father, André, harbors a wild thirst for danger that burrows in his personality and threatens his family. We see this in the opening scene when André takes his children to sit in his truck over railroad tracks. As the train barrels toward the family, André pretends the truck has stalled until the last possible moment. Antics like this one terrify and thrill his children. Then there is the darker side, the sunken eyes and secrets. After the family’s escape from André—and that’s how it felt, kids packed in the car, speeding across the Canadian border in the middle of the night—Béchard blames his mother for taking him away from his father. In the years leading up to his fifteenth birthday, Béchard discovers pieces of André’s criminal record and resolves to move back in with his father. His hope to quench his fascination with André’s past is shadowed by the realization that his father is not the same man he remembers from childhood. Béchard explores what it means to be in limbo between craving a father’s love and being repulsed by his lifestyle. In his memoir, the author appears troubled, wanting nothing more than a strong patriarchal figure as he picks fights at school and writes dystopian fantasies in his bedroom. But his redeeming qualities are limited. He, like his father, is charming when needed, but selfish, existing only to further himself regardless of his family’s needs. He is impassive, rough, and manipulative. He is a fighter. As André says to his son over dinner at a Greek restaurant, “You’re like me that way.” And it’s true. Béchard marks his adolescent years with a big mouth that spews lies intended to get the attention of the tough kids. He craves to be like his father during his years of robbery.

Béchard’s selfishness seems to be pitted against his father’s, bringing about the idea that father and son are mirror images of each other while still opposing forces. The two exist as foils—characters who emphasize their traits based on the contradictions of the other. Béchard’s driving force is his need for answers while his father runs from questions. Both men are stubborn, boxing with the idea of what the son should become based on what the father used to be. André’s shrewd demeanor threatens to bring his son down by attempting to dupe him into dropping out of school and becoming a boxer, while Béchard wishes to stay in school. André doesn’t want what’s best for his son. Béchard, in turn, mirrors his father by manipulation—he runs away when faced with a choice he dislikes, and then later uses it to threaten André. Despite the fact that his father is nothing more than an angry, aging man, Béchard is haunted by the unanswered questions of André’s past crimes and mysterious family. The memoir introduces a paternal relationship that is filled with uncertainty. There are fathers who are active in their children’s lives and there are fathers who are not. At first, André is a large component of his son’s life, and then he is out of the picture, and then back in. An unstable father affects his child, and in this author’s case, creates a son that is willing to drop his mother and siblings at any cost if it means finding the father whom he feels abandoned by. Béchard forces us to look closely at the relationship between father and son—how an erratic father who is absent in his son’s adolescent life and then thrust back into it can cause more harm than if he had skipped out altogether. Although the memoir is successful in showing the tension between father and son, at times there seems to be too much of the tension and not enough of the narrative. There are scenes in which Béchard sits in his bedroom and narrates the pros and cons about his father. Scenes like these do little to further the plot. As the story moves forward, Béchard is absorbed in André’s crimes with alarming focus, but is then indifferent when André is willing to spill all. Here Béchard displays the idea that the interest he has in his father’s enigmatic past lies in the pursuit of it. This changes when the secrets are ready to be let out because Béchard wants to believe his father is still the dangerous and intelligent man capable of robbing banks and pounding fellow inmates into their graves. André, at first, is mysterious. But as the mystery wears away, sympathy takes its place, something his son is unwilling to give. This change in the plot shows that as the author gets older, he is aware that the similarities he shares with his father are negative ones. Cures for Hunger exhibits Deni Y. Béchard’s ability to examine an unstable father/son dynamic and the family-fraying results. By pitting the two against each other and comparing their motives, Béchard creates a memoir that showcases a strained but caring relationship and how it develops over time.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed