The biggest question we as humans can ask is: “Why?” The contemplation of our mortality frequents art in many forms, and Grzedorz Wróblewski’s poetry not only contemplates the human experience, but also discusses what it means to exist in our current society. His writing sheds light on topics like capitalism, heteronormativity, and the normalization of violence in a way that is new and abstract. The reader must want to actively seek out what the meaning of each poem is and, by doing so, they become closer to the topic that Wróblewski selected to discuss.

Grzedorz Wróblewski’s Dear Beloved Humans, is a collection of poems spanning multiple decades of authorship. Born in Warsaw in 1962, Wróblewski grew up in the creative communities and culture of Poland where he began his career as a poet and artist. In 1985, Wróblewski emigrated to Denmark, prompting a shift in perspective and a new form of inspiration for his poetry. As I read through this collection, I found myself understanding the turmoil that Wróblewski felt over the course of his life and the humorously analytical and at times nihilistic way in which he portrayed his surroundings in his writing.

1 Comment

Temptation, angst, and lunacy all rear their heads as Sheena Patel explores the obsession that comes with unrequited love in her debut novel I’m a Fan. The fan in question is an unnamed narrator who has wrapped herself up in an affair with an aloof, womanizing older man. Patel, an established poet, chronicles the bad decisions of the unnamed narrator through blunt but enticing prose. Patel puts stock into the power of fan presence, linking political influence to the number of devoted followers one has. The narrator, a woman of color with little recognition, pales in comparison to the white female influencers with whom she must compete. She speaks to privilege packaged as #goals, to algorithms and whiteness discounting indigenous and black and brown creators, and to the universal immature desire to be liked.

As a fellow member of the Dead Parent Club™, Stephanie Austin’s Something I Might Say caught my attention because it made me want to compare notes on grief. In this brief collection of nonfiction essays describing an even more brief portion of Austin’s life, she explores the many layers of grief that overwhelmed her in just a few months' time due to back to back losses in her family. If you have experienced significant loss in your life and yearn for someone who can genuinely empathize, not just sympathize, then this collection of bite sized essays is for you.

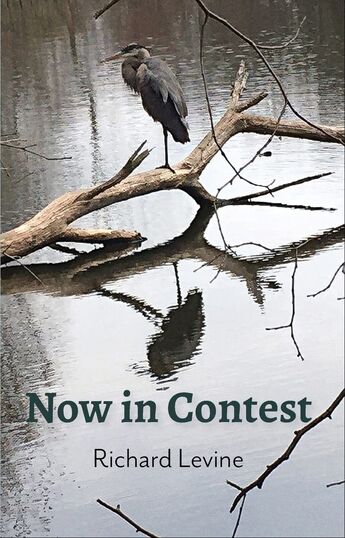

Human beings are born to connect emotionally with one another, hardwired to feel a range of emotions which are dependent on our situation and surrounding environment. In his collection of poems, Now in Contest, Richard Levine explores what it means to be human when life seems to throw so much negativity into the world. How do we carry on when it feels like we’re drowning? Levine shows the heartbreaking nature of what mankind is capable of, but also the beauty in the little things that we as a society collectively enjoy; the shared emotional connection that we have not only with each other, but the world around us. Through emotional imagery, metaphor, and symbolism Levine is able to take the reader on a journey of self-reflection, as he juxtaposes the spectrum of human emotion.

“Change is the only constant,” Chelsea Stickle writes in “Worship What Keeps You Alive”, the first flash fiction piece of her chapbook. This quote perfectly encapsulates Everything’s Changing, where nothing’s as it seems. The world has changed and the possibilities are endless in Stickle’s book, but one thing is as prevalent in this book as it is in society, and that’s the struggles of women and girls. Stickle uses absurdities throughout the book to tell stories, depicting women attempting to navigate a world that doesn’t like nor respect them. The problems women face are often overlooked, but Stickle reimagines these problems and tells them in a way that’ll have readers begging for more.

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed