The biggest question we as humans can ask is: “Why?” The contemplation of our mortality frequents art in many forms, and Grzedorz Wróblewski’s poetry not only contemplates the human experience, but also discusses what it means to exist in our current society. His writing sheds light on topics like capitalism, heteronormativity, and the normalization of violence in a way that is new and abstract. The reader must want to actively seek out what the meaning of each poem is and, by doing so, they become closer to the topic that Wróblewski selected to discuss.

Grzedorz Wróblewski’s Dear Beloved Humans, is a collection of poems spanning multiple decades of authorship. Born in Warsaw in 1962, Wróblewski grew up in the creative communities and culture of Poland where he began his career as a poet and artist. In 1985, Wróblewski emigrated to Denmark, prompting a shift in perspective and a new form of inspiration for his poetry. As I read through this collection, I found myself understanding the turmoil that Wróblewski felt over the course of his life and the humorously analytical and at times nihilistic way in which he portrayed his surroundings in his writing.

1 Comment

Nature is boundless: it covers just about everything we know. And yet, as modern technology progresses, nature has somewhat morphed into a monstrosity in our everyday lives. Many people today fear the unknown depths of the natural world and shy away from exploring it too closely. What might we be missing out on by avoiding nature in all of its pure and chaotic glory?

Adam Tavel’s Green Regalia answers this question, among others. Tavel explores the more comforting aspects of nature through fresh metaphors and experimental phrasing. In all of nature’s chaos and climates, there exists an atmosphere of comfort that Tavel draws attention to. Tavel’s environmentally-themed collection begins with a poem titled “How to Write a Nature Poem.” This poem serves almost as an epigraph, foreshadowing the rest of the collection, which artfully guides the reader through understanding the environment’s present and prevalent hold on our lives. Through use of nature images, Tavel creates deeper themes surrounding family, identity and finding solace in uncontrollable external factors.

Hostage: a person seized and used as security for the fulfillment of a condition. Someone who is specifically held captive so that other people will act according to the will of their captors. So what does poet Laura McCullough mean when she likens women to hostages in her newest poetry collection?

Women and Other Hostages is McCullough’s seventh and most recent collection of poetry. Excluding her prologue piece, this collection is split into five separate sections for the reader to view. Her poems act as a looking glass, allowing the reader to experience the world from an entirely female perspective and see the joys and struggles of the everyday woman. The myriad of poems she presents display a range of emotions from the freedom of selfhood found in “Women & The Syntactical World” to the unquestionable pain demonstrated in “The Will.” McCullough pours her soul into each piece and proudly displays her own battles to bolster others.

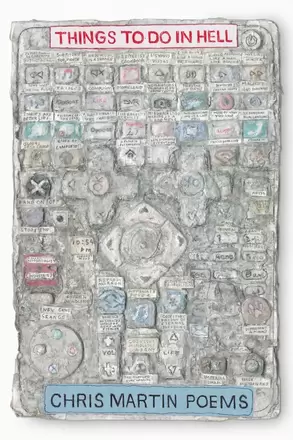

In his collection of poems, Things to Do in Hell, Chris Martin depicts the mundane in all its hellish glory. Its title sets a tone for the dichotomy within, seemingly belittling the grandeur of hell. His poetry brings attention to life and death, light and dark, pain and mercy, the quotidian and the grandiose. His poems are accompanied by unsettling drawings of everyday objects. These objects, covered in words, act as a sort of visual poetry, going beyond the standard line-by-line poem. The only way I can describe the aesthetic of this book of poetry is a creative, sometimes calm and untheatrical, display of ennui that attempts to connect earth and hell.

On her dedication page, Cherene Sherrard indicates her poetry collection, Grimoire, is “[f]or the mothers.” I am left with the following question: what makes a mother a “mother?” Is it the nine months of carrying a child in the womb, giving birth, and then raising said child? Or is it simply the act of loving a child, despite not ever meeting them due to gestation or birth complications?

I ask this question because many of the speakers in Grimoire are childless, either due to miscarriages, complications, or stillbirths. Are they included in Sherrard’s dedication to “mothers”? Can they even be considered mothers without living children? These mothers in Grimoire, who have lost their babies, are Black mothers in America, and for many, they have lost their babies due to factors out of their control such as miscarriages and institutionalized racism. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed