Shirley Bradley LeFlore’s debut poetry book, Brassbones and Rainbows, is a vivid collection that uses a musical voice to address political and social issues. LeFlore’s word choice throughout her poems evoke the feelings of gospel and blues, and when reading the poems you don’t hear the writer’s voice speaking to you; it shouts and sings with passion you can feel in every line.

Many of the poems in the collection are written in a voice that shouts from the page, making one picture the poet as one who is fighting against being silenced. While the words in the poems don’t specifically say who or what is trying to silence the poet, the undertone of racism and prejudice stands out as the ideology the poet is preaching against. The need to shout out loud and be heard is perhaps best expressed in the closing lines of her poem “Brass Reality,” which reads, “you can bury me in the east / you can bury me in the west / but I’m gonna rise-up and be a TRUMPET in the mawnin.”

0 Comments

A heavily populated Saturday afternoon echoes a literal mutter throughout the Mütter Museum, the living mingling amongst the dead, their voices hushing as a wall of skulls greets them beyond the foyer’s marble stairs. Even those who have been here before (including myself) cannot help but ponder the mummified past, the wax figures of the disfigured, and the alternately gleaming and rusting obstetrical tools which look more suitable beside a Torquemada or Mengele than in jolly old Franklin’s adopted hometown.

Above, the special exhibits room looks almost sterile, newer than its surroundings, reminiscent of Museum of Modern Art austerity, white walls and carefully spaced pieces, granting viewers a hint of intimacy. Below, thin and creaking wooden steps lead to crowded collections in jars; the sample and trifles and oddities of humanity which repel and draw the curious and strong of stomach. The reverse chronology of architectural and exhibition styles suit the venerable institution, a bequest of the University of Pennsylvania College of Physicians, and set in motion a walk backward through time into the American medical establishment.

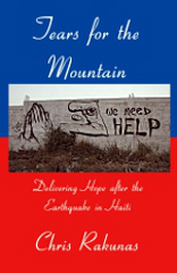

In the United States, where our national attention span seems to coincide with the length of a half-hour TV sitcom, it’s no surprise that the deadly, destructive earthquake in Haiti has disappeared from our national consciousness.

The January 12, 2010 quake killed more than 100,000 men, women and children and left tens of thousands more homeless. News reports at the time told of office building collapses in the capital of Port-au-Prince that buried scores of people alive under tons of debris. In the days and weeks that followed, orphaned children wandered the streets and roaming gangs enforced vigilante justice while looting homes and businesses for food and valuables. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed