|

A heavily populated Saturday afternoon echoes a literal mutter throughout the Mütter Museum, the living mingling amongst the dead, their voices hushing as a wall of skulls greets them beyond the foyer’s marble stairs. Even those who have been here before (including myself) cannot help but ponder the mummified past, the wax figures of the disfigured, and the alternately gleaming and rusting obstetrical tools which look more suitable beside a Torquemada or Mengele than in jolly old Franklin’s adopted hometown. Above, the special exhibits room looks almost sterile, newer than its surroundings, reminiscent of Museum of Modern Art austerity, white walls and carefully spaced pieces, granting viewers a hint of intimacy. Below, thin and creaking wooden steps lead to crowded collections in jars; the sample and trifles and oddities of humanity which repel and draw the curious and strong of stomach. The reverse chronology of architectural and exhibition styles suit the venerable institution, a bequest of the University of Pennsylvania College of Physicians, and set in motion a walk backward through time into the American medical establishment. The most modern of these works-on-view, “Blood Work,” is the brainchild of New York artist Jordan Eagles, whose web site describes the self-invented process as “preserve[ing] blood to create works that evoke the connections between life, death, body, spirit, and the Universe…”

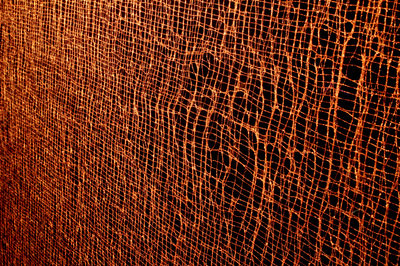

Plexiglas and UV resin hold the blood captive, revealing a luminous glow, an unsettling powdery essence “as a sign of passing and change,” and mixes in copper as a “unique, fiery energy.” Along one wall, “Roze Triptych” captures blood as textile, “a map of memory and homage to ancient wrapping rituals.” Indeed, each cloth-permeated piece could be batik, a fabric of the life force as its substrate once flowed. Eagles isn’t the first artist to use blood as a medium. Modern feminist pieces, from spoken word to the 2008 outrage surrounding Yale University art student Aliza Shvarts’ use of her own menstrual fluids (and self-induced miscarriages, depending on whether you believe Shvarts or a suddenly gun-shy Yale), place a high premium on blood and its symbolism. Why not use one’s own body in the manifestation of art? Why not capture the force upon which life flows? Why not make the figurative literal and the intangible physical? Who gets to decide which artworks are creation and which artworks are destruction, and why destruction isn’t art? On the issue of art or “art,” the casual Googler will find a million and one comments at varying levels of rational discourse. However, the discussion’s very existence strongly suggests the work has indeed created a narrative to which even the most valiant anti-art fanatic has dipped a toe. With this narrative, the artist can claim success. As the blood in Eagles’ work did not issue from his own body, perhaps he dodged the gender politics and/or personal ethics bullet. The animal rights folks (Eagles sourced the blood of “Blood Work” from a slaughterhouse) never made anything remotely approaching the mass media splash that the pro-life (and pro-choice) people did for Shvarts’ Internet-famous conceptual piece. I manage to tear my gaze from Eagles’ backlit blood paintings, glowing gold and red and in some spaces, deep black. Where, exactly, does “Blood Work” fit into the historical Mütter? Downstairs, the main collection remains shadowed in original wood cabinetry, scrupulously maintained, yet the glass’s shiny waves betray the age which blamed “miasmas” for spreading infection. Unhindered, modernity creeps in around the corners: numbered cards, far more recently installed amongst the flesh and bones, offer viewers a cell phone tour. Then around the corner, on the opposite side of a descending staircase, the revolving exhibit presently entitled “Broken Bodies – Suffering Spirits: Injury, Death, and Healing in Civil War Philadelphia” beckons, in sharp contrast to the glamorous and sterile bloodwork which drew us to the museum space in the first place. Another corner, and the bloodless “Soap Lady” in her open casket wordlessly questions everything the nineteenth century knew about bodily decomposition. Why she’s tucked away in a corner of the Civil War, I don’t know, but standing between her and a model of Abraham Lincoln’s head wound is suddenly overwhelming. Enough blood and bodies for one day. I walk down marble steps, a feature one might expect of a museum, whether or not it contains art or “art.” Eagles has chosen a brilliant venue for his work: the crossroads of art and exhibit case, life and death, energy and repose. Choose your dichotomy: Eagles has articulated the connection between them.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed