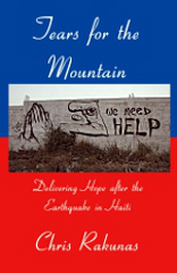

In the United States, where our national attention span seems to coincide with the length of a half-hour TV sitcom, it’s no surprise that the deadly, destructive earthquake in Haiti has disappeared from our national consciousness. The January 12, 2010 quake killed more than 100,000 men, women and children and left tens of thousands more homeless. News reports at the time told of office building collapses in the capital of Port-au-Prince that buried scores of people alive under tons of debris. In the days and weeks that followed, orphaned children wandered the streets and roaming gangs enforced vigilante justice while looting homes and businesses for food and valuables. Despite an initial international response that led to more than $32 million in donations in less than a month, the scores of similarly horrific disasters since – including the current typhoon recovery underway in the Philippines – have shoved the Haiti story completely off the mainstream media radar. A quick Google search of the phrase “relief efforts in Haiti earthquake” produces recent releases from the Red Cross, CARE and the Obama White House. However, articles from such mainstream news sources as CNN, the Washington Post and the Christian Science Monitor carry publication dates as old as only a few days and weeks after the quake itself. Filling this informational void, however, is a powerful nonfiction chronicle called Tears for the Mountain. In his debut work, Chris Rakunas vividly shares his week-long experiences delivering ten tons of medical supplies throughout Haiti. Originally published on January 12, 2012 – the second anniversary of the quake, Tears currently is receiving renewed attention due to the Philippines disaster along with the pending release of Rakunas’ third book, and second novel, The Eye of Siam. The goal of narrative nonfiction works, such as Tears, is to provide detailed information about key situations, events and issues. Just as the Greek god Chronos wrapped his snakelike body around the legendary world-egg; a strong chronicle should wrap its arms around a topic and give us a comprehensive, opinion-free, non-judgmental account of what took place. Tears meets and exceeds this goal by delivering the sights, sounds, feelings and smells of what it was like to be fully immersed in the hopeless tragedy that was immediate post-earthquake Haiti.  Chris Rakunas Chris Rakunas The fast-paced book begins with Rakunas, at the time a southwest Florida hospital executive, racing across the state’s Alligator Alley highway to catch a cargo flight to Haiti two weeks after the quake. He and his orthopedic surgeon colleague, Dr. Stephen Schroering, are making the trip with nine pallets worth of surgical goods that were dropped off at their hospital. From their middle-of-the-night arrival at the darkened Port-au-Prince airport – illuminated only by the light of an electrical fire in the remains of the terminal – to their exhausted departure six days later, Tears chronicles the pair’s experiences interacting with the Haitian people in exacting detail.

We can see the brightly colored orange, green and blue piles of wood shards along roadsides where small houses used to be, as well as the hundreds of boxes of supplies that Rakunas spends hours sorting and organizing and sorting again. We can hear the joyous laughter of young children playing outside the orphanage Rakunas called home for a week, which stands in stark contrast to the plaintive wailing of mothers over the bodies of their dead babies. We can feel the old man’s damaged thigh bone snap into place as Rakunas assists with the resetting of a fractured leg on a makeshift church pew operating table, and we share the feeling of fear with the author as he sprints to seek shelter behind a courtyard gate to avoid a gang of Port-au-Prince thugs. We can smell the pervasive burning charcoal aroma throughout the island, along with the sickeningly sweet odor of rotting human flesh that is seemingly encountered around every corner. The chronicle also introduces us to such inspiring personalities as Miriam Frederick, the director of New Life Children’s Home and Rakunas’ host and facilitator for the week. She’s described in Tears as a both “a miniature Phyllis Diller” and “the Mother Teresa of Haiti” for her appearance and her countless good deeds. We also meet the complex Guy Philippe, a local political leader who was quite helpful to the author on a delivery to the remote town of Pestel. We learn in the book’s epilogue that Philippe is suspected of being a murderous counter-revolutionary who was trained and funded by the U.S. government. Tears for the Mountain – named after graffiti in Port-au-Prince depicting a map of Haiti with its tallest mountain Pic la Selle crying – is faithful to its time line and organized into chapters simply titled Day One, Day Two etc. We awaken with Rakunas each morning to the sound of giant cargo planes touching down at the airport and go to bed with him each night after the bracing, but refreshing, ice-cold shower that washes away the physical if not the emotional stains of the day. In a recent interview, Rakunas said he’s constantly haunted by strong, sensuous images from his trip, an effect he said is intensified each time he attends a book signing and speaks publicly about the trip. These experiences so strongly felt by Rakunas nearly three years ago are effectively recorded in Tears for us to process and ponder in our own minds. With his repute as a novelist continuing to grow, one hopes Rakunas eventually will step back into the nonfiction genre as he clearly has a firm handle on what it takes to produce a strong and significant chronicle.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed