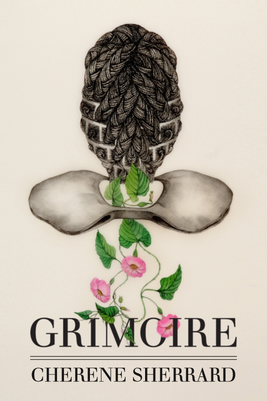

On her dedication page, Cherene Sherrard indicates her poetry collection, Grimoire, is “[f]or the mothers.” I am left with the following question: what makes a mother a “mother?” Is it the nine months of carrying a child in the womb, giving birth, and then raising said child? Or is it simply the act of loving a child, despite not ever meeting them due to gestation or birth complications? I ask this question because many of the speakers in Grimoire are childless, either due to miscarriages, complications, or stillbirths. Are they included in Sherrard’s dedication to “mothers”? Can they even be considered mothers without living children? These mothers in Grimoire, who have lost their babies, are Black mothers in America, and for many, they have lost their babies due to factors out of their control such as miscarriages and institutionalized racism. The voices of Grimoire’s speakers recall their experiences of loss before or during childbirth due to complications stemming from the physical to social, such as genetic factors and the past and present racism steeped in America’s healthcare system. Systemic racism is further explored in the second half of the collection, which is prefaced with “the grim statistics/of racial math” as Sherrard puts it in the first two lines of “Oracle at Venice Beach, 1995,” one of the poems in the latter half of her collection. It is important to note that Sherrard takes inspiration from Black creators and mothers before her, and in her poems, she explores the deep, ancestral pain of Black mothers in America through baking imagery, corruption and slavery language, and miscarriage and devastation comparisons.

In the first part of the collection, Sherrard is inspired by the deceased Black mother and author, Mrs. Malinda Russell, as she reimagines recipes from Russell’s cookbook. In “Marble Cake”, the speaker details how she creates the “white” and “dark” of her mixed-race son. But this act of creation, baking or gestation in the womb, is worrisome for this speaker as she states, “It was months before I accepted/I was carrying another human being” (4-5). She is nervous over his formation, if problems will arise while he bakes, which is a valid concern given the high Black infant mortality rate, which this speaker is cautiously aware of. It is evident this worrying is warranted when the speaker later states, “Mixed children usually/come out beautifully. The doctor is unsure about mine” (13-14). This doctor believes the child is not beautiful because he believes he was baked incorrectly or perhaps had tainted ingredients. The speaker provides no evidence that her son is not beautiful which supports the idea that this doctor participates in systemic racism as he unfairly denies the speaker’s son the label of “beautiful.” It is also vital to note that although this discrimination may come as a surprise to many white readers, as it is expected of healthcare professionals to typically believe all life is beautiful, discrimination in the healthcare system is a burdened reality for Black people in America. This concept of the tainted womb of a Black mother is also seen in “Weathering” in which corruption language is present. A genetic counselor explains to a young Black mother how a DNA anomaly in “your people” (8), or Black people, is caused by a “toxicity that seeps and creeps until your/womb is all black mold in need of remediation” (10-11), which is why her pregnancy is high-risk. The word choice here, “toxicity”, “seeps”, “black mold” holds negative connotations for a Black mother’s womb, a place which is typically thought of as nurturing, sacred, and beautiful as it is the place where life grows; however, this genetic counselor judges this Black mother’s womb more as a festering wound than a space of life due to an abnormality she finds in this young woman’s genes, an abnormality out of her control. On October 2, 2020, I attended the Autumn House Press Fall Release Virtual Reading Party hosted by White Whale Bookstore, and I had the opportunity to hear Sherrard read some of her poems. According to Sherrard, the poems in the second part of Grimoire meditate on child bearing and infant mortality. She explained how she was inspired after reading Linda Villarosa’s 2018 The New York Times Magazine article, “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis.” In fact, Sherrard includes the following quote from Villarosa’s article on the first page of the second part of her collection: “Black infants in America are now more than twice likely to die as white infants--11.3 per 1,000 black babies, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 white babies, according to the most recent government data--a racial disparity that is actually wider than in 1850, 15 years before the end of slavery, when most black women were considered chattel.” This is a reality which Sherrard says shocked her, although should not have surprised her. We can see this reality in her poems in her second part of the collection. Returning to the poem, “Weathering,” the pregnant speaker further expresses how she experiences traumatizing treatment in the hospital by relaying how she was treated. Language connected to slavery such as “secures the shackles” (16), springboard this speaker into feeling like a slave as she is strapped into stirrups or shackled, and on display in front of a white coated audience, much like a slave at auction. Given how these health professionals treated her body, she felt as if they were saying with their actions, “This science/is for saving lives that matter, not salvaging slaves” (13-14), as they restrained and exposed her body on the hospital bed. This particular quote may resonate with Black mothers who have lived through these acts of childbearing cruelty, and unfortunately, perhaps may have also lost their babies to a broken, racist healthcare system which does not value Black lives, even before they enter into the world. Sherrard continues to express the past and present pain of Black mothers in America through miscarriage and disaster comparisons in poems such as “Dixie Moonlight” and “Red Tide.” In both of these poems, it is evident the speakers suffer miscarriages given the comparisons to natural weather disasters. Miscarriages themselves are a disaster of nature, so this clear comparison is strengthened through vivid devastation language which relates to both miscarriages and natural disasters. In “Dixie Moonlight,” the speaker compares her miscarriage bleeding to natural disasters, such as Noah’s flood and Hurricane Katrina, and how her blood is like “water seeping up through/cracked foundations” (8-9), spilling from her damaged uterus. This combination of a damaged uterus and the leaking “evidence” of the resulting devastation, illustrates the harmful impact of the miscarriage. In the final two lines, the speaker’s natural, bodily disaster comes to one final swell when she says, “this placental blood/is an abrupt surprise” (11-12), like the devastation caused by natural disasters, such as floods and hurricanes, is a surprise to unprepared victims. In “Red Tide,” this miscarriage and disaster comparison can be seen again in the first two lines: “we wade into a channel sluggish with pink foam,/like a tube of tomato paste has been squeezed.” The speaker describes her pool of blood as tomato paste and pink sea foam. The title itself reminds one of a disastrous, inescapable wave of blood that the speaker is hit with unexpectedly and is left feeling helpless in the wake of destruction, the loss of her baby--a loss many Black mothers unfortunately face in America. Throughout Grimoire, Sherrard forces her readers to face the reality of our racist healthcare system in America and her speakers prompt us to no longer be complacent in our worldview. Black mothers and their babies are still suffering from unequal treatment, but since we are now aware of this suffering, we must no longer remain silent.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed