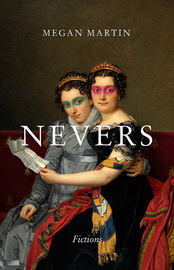

Megan Martin’s Nevers throws you head first into the mind of a manic-depressive writer in a sinking relationship, rarely slowing to answer your questions. The unnamed narrator is every artist dissatisfied with life, raging against their peers, their lovers, their mothers, and most of all themselves. Martin’s prose delivers a punch to the gut followed by a gentle pat on the head. And then it punches you in the gut again, but while you’re still reeling, it does a handstand and you can only look on in bemused delight. Martin captures the feeling of cyclical depression with startling accuracy. The self-described fictions, too short to be vignettes and too interwoven to be short stories, wind through the peaks of one woman’s odes of love, climbing the cliffs of her manic fever dreams only to drop down into dark valleys of self-loathing and rage. The first few pages are a confession, the narrator declaring to her lover “you are the most amazing creature ever to straddle this planet.” A few pages later, however, the narrator admits that she longs to romance other people, that she will “tell you I love you" and then immediately "worry about running out of eggs,” going through the ordinary motions of daily life despite being unhappy. This kind of mood whiplash can be disorienting, but in the case of Nevers, that’s a good thing. Riding another person’s sharp mood swings should be disorienting, even overwhelming, because depression is overwhelming, and Martin captures not only the extreme overwhelming lows, but the opposite overwhelming highs. This depression and mania manifests realistically, and paints a portrait of an author coming to terms with their own status as average. As Nevers progresses, the narrator relates this tedium with her decision to live in suburbia: “I am not sure how I became a person who lives here,” she wonders at a pool party. “I wanted to cry. I am too young to have anything to say about real estate! I hope never to have anything to say about it!,” she laments later. The narrator is an artist, but one who despises her colleagues, resents being a responsible adult, and hates her ordinary romance.

The narrator's straightforward revulsion at the mundane makes the more surreal and metaphorical aspects of Nevers difficult to understand at first, with some description bordering on allegory. But in the end, it’s a pleasurable read. It gives an accurate look into the whirlwind mind of a struggling artist, and an intense glimpse into the illogical and damaging mindset of depression. It can leave the reader emotionally wrung out from the intensity, but its overall message is one of solidarity: you aren't the only one feeling this way. There are hundreds of thousands dissatisfied and simply living despite their dreams, and this in its own twisted way is one of life's beauties.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed