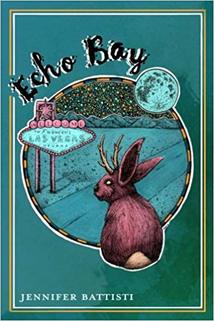

In Jennifer Battisti’s first chapbook, Echo Bay, we meet a multifaceted and singularly articulate girl and woman, raised on the fringes of the Las Vegas Valley, navigating the complexities of memory with moving poetic detail. The speaker is at once enrapturing and unabashed, exploring adolescence, marriage, motherhood, and grief with both precision and universality. Through Battisti’s unique perspective, we examine the shaded, much less glamorous fringes of the Las Vegas Valley, just as we are presented with the much less idealized aspects of motherhood and marriage. Battisti’s profound work fosters an intensity of emotion which ranges from despair to joy to acceptance as the speaker searches for the freedom of letting go. She waits... to scour out the marks-- Nearly all the concepts and ideas discussed in this collection spring forth from the landscape. Battisti herself, in an interview with the Clark County Parks & Recreation Department, claims that she is “interested in...weaving the iconic and the indigenous in Vegas.” As a Vegas local, she presents in her chapbook a view of the area in a personal light, mirroring the profoundly personal subjects she explores otherwise. In “Valley of Fire,” she describes that a “road slick with sun / spreads easily, like a woman / opening her inside parts.” Amidst other images of off-duty showgirls and Elvises, a nearby electric power plant, small houses, and Def Leppard playing in the desert heat of summer, the Mojave is described as a mother in “View From Lone Mountain”: The Mojave cradles These feminine, reproductive metaphors with which she describes her hometown and childhood experiences blend brilliantly with her incisive commentary on being a wife and mother. This commentary often has a strong undercurrent of trauma or tragedy, which is similarly paralleled with the natural surroundings. In her poem “The God of Small Deaths,” Battisti recounts her journey from trying to get pregnant—“I prayed for the absence of shedding”—to eventually experiencing a miscarriage. Here we see a distinction between before and after, reassimilating to a life after a seemingly irrevocable transition into the “universe” of pregnancy. An innocent debut image of doves singing during her breakfast focuses in on a darker dove that flees the scene as the speaker begins to “leak fuchsia.” She recounts her trip to the hospital with concrete imagery, and ends the poem thusly: Later, I left with the lie This is a tragic and explicit mention of the concept of “lingering,” which is encompassing for this collection as a whole. In this work, Battisti explores memories and emotions that sting and ravage the mind and body—which linger and, more substratally, need to be let go of. This can be seen just as prevalently in her poems surrounding the end of her marriage. Though they mark a significant transition, there is a stagnancy in these poems—a quiet, surprisingly curious period of finality following a decision made unspoken. Most notably, the poem “The Resurrection” reimagines an attempt to revive the marriage as a ritual. The marriage is described as a “forgotten heap,” and despite the attempt, we see again the resignation to the outcome of the marriage: “We are tired. Belief, light as a feather, stiff as a board. / We circle the mass like giant grieving elephants.” Amidst this sense of surrender in her collection, Battisti is expertly able to explore that which grows and thrives in spite of that which lingers. Most literally, in poems like “The First Week,” “Jackalope,” and “Communion,” she examines the experience of having a child and watching her grow. She describes the irreversible change of life after giving birth, a forfeit of autonomy and yet a journey into the joys of being a mother: “I felt the deep pull of motherhood. / The glorious becoming by a ferocious undoing.” In “Communion,” we see a collision of the concepts of transformation and lingering, as she describes her “hips haunted by the phantom / baby straddling the notion of being separate.” She describes her placenta, shared with her daughter, as their “first Communion,” conveying a profound closeness and love that comes naturally and, despite the trials of motherhood, brings her a sense of oneness and peace. This collection of poetry is a uniquely powerful examination of transition—into adulthood, into motherhood, and at the same time out of adolescence, out of pregnancy, and out of marriage. Just as Battisti as a speaker accepts her need to leave behind the hot, boisterous charm of her youth in Vegas, she demonstrates a steady yet emotional determination to let go in many aspects of her personal life, mirroring the two aspects poetically. However, just as the speaker must transition and continue to grow, Echo Bay makes it clear that she will never forget where she came from and, more effectively, what has shaped how she views her newfound family and sense of love; in “Fishing at Midnight,” Battisti makes this simultaneously uncomplicated and deeply impactful observation: The moon hovered

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed