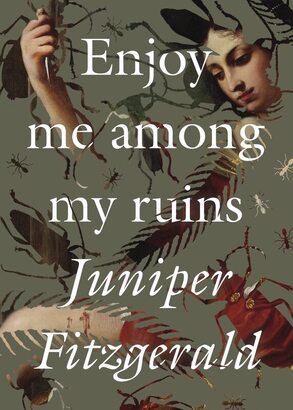

As with any book review, I know I have an obligation to remain professional in the following paragraphs. But Juniper Fitzgerald forces me to be personal in every letter that bleeds through the choreographed motion of my fingertips on this keyboard. I almost want to conduct this as an open letter to Juniper, a “thank you” note that wouldn’t be nearly as impactful as I hope it could be. But that wouldn’t be fair to Fitzgerald or her story, or to the stories of Jean, and Cassandra, and her Grandma, and Theresa, and Diana, and Marita, and Anita, and Dakota, and Andi, and Jennifer. Trigger Warnings: Sexual abuse/assault, sexism, sexual violence, consensual yet gore sexual descriptions. Fitzgerald is a mother, former sex worker, and academic based in the Midwest. Her essay collection is a perfectly composed mosaic of her life, with stories that at times were hard to read. And it’s because they are hard that they must be read. The first thing a reader will notice upon opening Enjoy me Among my Ruins is the fact that every single detail is meticulously thought out. The structure that dictates the pace of this collection is genius, described in her author’s note as a “nonlinear, kaleidoscopic structure.” Fitzgerald’s story is told hybridly, with letters/profiles about the women in her life, followed by excerpts of her very private confessions to Gillian Anderson—which is the name of her childhood diary—and deeply personal braided essays. There are a lot of triggering subjects in her pages; the rawness Fitzgerald uses to walk the reader through her essays is truly a sensory experience, and I found myself flinching reading through some of her descriptions. In the second essay of the book, “Dead Bugs,” Fitzgerald writes about her past Humbert Humberts (a reference to Lolita’s abuser): “We have sex in an abandoned house and then, later, we find a cheap apartment with stained carpets off the interstate. My Humbert Humbert gives me little things. Pills. Cigarettes. Money. He [f@#$%] me with an empty wine bottle just to see” (20). Her life as a sex-worker is deeply explored within these pages. As a reader, and someone who didn’t really know a whole lot about this topic, besides the widely romanticized Hollywood classic Pretty Woman (1990), I chose to face these parts of the books as an opportunity to be educated on this subject. And she so brilliantly walked me through this reality; her in depth, metaphorical, amazing descriptions, told me everything I needed to know: “This is what it is like to walk into a strip club: the cut of the spectacle is deep enough that initially the only thing you feel is the heat. If you can handle the dagger of it, the way it plunges through flesh and bone, there are scars and prayers to be had too” (4). The essays about motherhood and the stigma of mothering a child, while also working in the industry, were some of the best writing I’ve ever encountered. The emotions, and the conversation she’s sparkling come alive more urgently on the page. There’s so much to be learned about this topic; from a craft perspective, Fitzgerald does an amazing job articulating her circumstances to readers through scenes that effectively portray her struggles. In the essay “Fleur-di-lezzie,” she includes some direct dialogue among other sex-workers about their relationship with motherhood and their career (another craft technique I found extremely effective to the narrative), sharing some atrocious misconceptions and deeply rooted prejudices embedded in the conjunction of the two roles. Fitzgerald points out: “When the wife-and-mother class is also the whore class, patriarchal domination is so threatened, so ultimately blanched and blinded by its own precarious ideology, that it digs its claws in deeper, threatening not only the safety of sex workers but of our children as well. [..] And so those of us who occupy these two classes simultaneously, those of us who must mourn the stigma and violence against sex workers on a daily basis, will continue to push back with images of lilies, of the fleur-de-lis, reclaimed and reimagined as both Madonna and whore” (27). Also on the topic of motherhood, Fitzgerald’s essay “Dear [Redacted]” is the one that truly brought me to tears. She made the stylistic choice of writing this essay (perhaps the most personal piece in the collection) in the form of a letter to her daughter. There is abuse and betrayal in her story, along with so much sadness, so much erasure, so much exclusion. This essay presents a different side of the author’s story, one that shows how even when among her ruins, the love for her daughter rises above everything else: “I love you. And I always have. I loved you before the creation of the universe and I will love you after it is gone. I would relive this life an infinite number of times just to be able to meet you again and again. And if you think that’s melodramatic in any way, then good—you’re clearly more adjusted than I am” (40). I found myself being extremely careful reading this collection – not in the sense of being aware of the triggering subjects, but paying very close attention. A lot of nonfiction writers—myself included—often write to express something they think needs to be heard and, consequently, cared about. When reading a personal narrative like Fitzgerald’s, I try not only to listen, but also to cherish every single word. I left these pages knowing so much more about a reality that isn’t my own—but, in some ways, it is. It is all of our stories, and perhaps that’s why it hurts so much. If you’ve ever found yourself needing a Gillian, or facing abuse, or living as a solo mother, or dancing on a pole in front of an audience of pigs, you’ll learn something about yourself in these pages. This book is about surviving as a human, and Dear Juniper, I thank you for that.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed