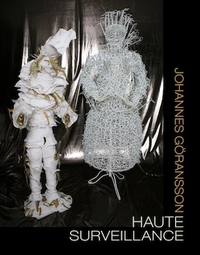

Johannes Göransson’s second novel, Haute Surveillance, first introduces his nameless narrator in the midst of confusion: he immerses his readers in a world of grotesque and vivid imagery, of “a thousand mute actresses with their mouths full of jewelry,” of a “cutting room” that is “full of soldiers masturbating.” He places readers in his piecework of violence, sex, art and emotion, in short snapshots of unexplained events, and leaves them scrambling to find their way out. Readers get one companion, one true character: an unreliable, determined, and probably insane narrator, and the reader slowly realizes this world is the narrator’s own. Göransson makes it clear from the very first page that the reality of the situation isn’t important, what is happening isn’t even important. The ideas are. Throughout the novel, the narrator remains something of a mystery. His view is the only one the reader knows: he gets no outside perspective. Readers can relate to some of the narrator’s anguish and torment without ever really knowing him. He often contradicts himself, saying, “I’m anorexic but I am full of fat. I’m the Real Thing, the boy with the headphones or the girl with the white out.” Then he’ll say, “My torso: The inflation crisis of the photographed body.” Then, “Someone tells me I have infants or infant shock and something has to be done about the cysts.” The confusion is natural. These are only a few of the many ways the narrator describes himself and his body. Readers reach for the connection, but the narrator stays hidden in his shell at a safe distance. Maybe he’s a veteran soldier. Maybe a father. Maybe an actor. And the term “he” here is used loosely; many gender barriers are crossed.

Yet, despite his apparent stagnation, the narrator does not exist alone. He puts other characters into a relatively (relatively being a strong word) clear context. For example, the Starlet is dead, definitely dead, but whether or not at the hands of the narrator is debatable. The Black Man, a constant threat to the narrator’s home at the Shining Mansion on the Hill, may or may not have escaped his own trial and may or may not be coming to kill the narrator for killing the Starlet. The Expresident, who seems to be in charge from an official title, is completely out of touch with the others around him. The narrator’s wife is full of “occult genius” who seems to understand the narrator better than anyone else, which mostly involves sex. His daughters are frequently impregnated: one, called “The World,” gets pregnant from licking a dirty towel and gives birth to six children at the same time. Readers only know these characters through the distorted view of the narrator; instead of connecting with them, readers connect with the narrator further. These stock, vague characters reveal the narrator’s own stereotypes, bringing the reader closer into his head and the chaotic, disjointed world. Other characters personify less clear ideas, like Father Voice Over, the Genius Child Orchestra, or Mother Machine Gun. Because they all influence the narrator in some way, not positively, they all have a definite place in the narrator’s life. The narrator, for example, realizes that “nobody can hear [Father Voice Over] talking. They think they’re hearing themselves think.” It’s hard to tell which characters are invented and which really exist in the narrator’s world, if any at all. The narrator himself as a thinking person is the only thing the reader can depend on. The narrator trudges through his patchwork life trying to solve something. Anything. He determines the way out of his rut is by killing someone, whether the constant reasoning of Father Voice Over or the insidious, omnipresent Black Man. He doesn’t know if he should listen to the Expresident or the naked soldiers who enjoy advising him through crafted plays. Once the narrator grabs this idea, however, the story moves forward. The narrator has invented a majority of this world, or at the very least compiled a stock of images that boils and froths until it threatens to spill over. But once he makes up his mind about an action, despite the action being murder, he can lift himself out of the observing position. The threat of violence acts like a forward momentum in an otherwise still atmosphere. As the narrator says, “It was the Real Thing.” He can influence the world, change the world. Is the world. Read Haute Surveillance without the expectations of a normal book and feel satisfied. Instead of characterization, let the flow of images and brutal one-liners create a whole picture. Instead of plot, accept what Johannes Göransson presents as the narrator’s reality. Every line feels intentional, building on a feeling or an idea. The emotional impact from the world of one man focused on the merging of the grotesque, the beauty, and the stereotypes is worth every page.

1 Comment

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed