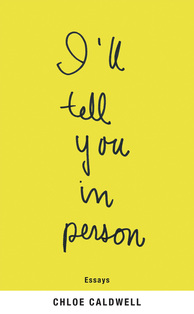

Some people seamlessly accept the maturity and responsibility that comes with adulthood. Some of us call our moms a lot. Some dig their heels into the ground with the resistance of a toddler heading to time out. Chloe Caldwell, by certain definitions, is the latter. Caldwell’s latest essay collection, I’ll tell you in person, includes lengthy but devourable essays about some of her craziest decisions, most obstructive and devastating problems, major disappointments, and the relationships that got her there. Caldwell tells stories in a, if nothing else, unique, refreshing, and unabashedly authentic tone. There's one about how she met men on Craigslist for meat (surprisingly, it’s not what it sounds like), one about how she didn’t meet her “Celebrity”, one (many) about how her addictions and her acne got in the way of any positive thing in her life, and plenty about her childhood best friends (the good and the bad) and her addict ex-boyfriend.

Many of us are familiar with the traditional bildungsroman: a coming-of-age tale composed with a perfect Freytag’s pyramid where, in the end, exists a lesson learned and maturity reached. Caldwell, however, in her life and with her words, takes this tired genre and turns it on its head. Instead of gracefully and properly making the transition to adulthood like she's “supposed to” (though whose job is it to determine that, anyway?), Caldwell’s experience reminds me of absurdism or a person flailing through time, hitting every obstacle, self-induced or otherwise, on the way. She is both the heroine (the other type of heroin is present, too) and the villain of her own story. Sometimes it's hard to digest a character (and even if this is nonfiction, she is just that) who trapezes over that line because it's in no way traditional. The reader sees Caldwell instigate the rough patches in her narrative with bad decisions and bad attitudes, but we also witness Chloe come out on top time and time again. Okay, maybe not on top. But she gets back up again every single time. The way Caldwell’s writerly voice encompasses boldness, bravery, and realness is enviable. She admits to all of the things the rest of us would never admit to thinking, let alone say out loud. She acknowledges her selfishness, her tendencies to toy with people, her immaturity, yet she’s never ashamed or shy or less real. It’s easy to admire Caldwell because, despite her flaws and issues, she views her life with a special kind of wit. Even though things were terrible for her while they were happening, she has since been able to face them with the acceptance and self-awareness everyone wishes they possessed. Many reviews of this collection discuss that when you close the back cover, you leave with a friend in Chloe Caldwell. With a title like I’ll tell you in person, I believe this was an intentional goal of hers: to address an audience on an intimate, personal, and friend-like level. And while I agree with the reviews, the outcome of this book has a lot more to do with self-realization, maybe even self-affirmation, than anything else. In fact, Caldwell tells us so, writing, “Sure, I am writing here about myself. Duh. But that’s not the point of this book or these essays. I hope you will project your mistakes and failures and heartache and joys onto mine. I hope you will feel a touch of participation mystique while reading about my sometimes poor decisions. Unless you’re perfect. In which case…” She trails off. Her experiences are unique and interesting, so only a very small percentage of people can relate to all, or even one, of them. It’s such an interesting dynamic that I so often found myself thinking, “this is me” as I read her words. I, along with many of Caldwell’s readers, feel an immediate connection. As cheesy as it sounds, maybe it isn’t Chloe we befriend, but ourselves. It is we who are addicted to pizza and scavenging for self-esteem and success. Caldwell simply reaches out a hand onto which we can grab. Caldwell recognizes that what she’s done, both in writing this collection and how she’s lived, are crazy and that there is a great chance nobody will care. But she also recognizes that she isn’t done growing up or living or experiencing. She writes that “The liberating thing about publishing an essay collection before you are a fully formed person is that there is nothing to fear. You have no readers. No experience. No memories of doing it before. No wounds.” But she lists these same reasons to describe “the bad thing about publishing an essay collection at twenty-five, when the frontal lobe has barely finished developing.” So here’s to Chloe Caldwell, fearlessly but fearfully trekking her way through NYC, Berlin, France, and adulthood, all the while saying, “I was almost home. I was getting closer to knowing what that meant.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed