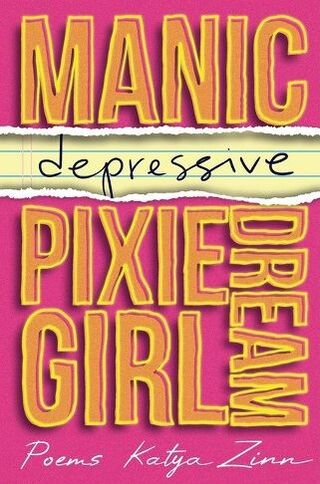

Katya Zinn’s first published full-length collection of stories, essays, and poems, titled Manic Depressive Pixie Dream Girl, is an extreme exercise in examining the damage done to women by capitalism, social constructs, neurodivergence, and the patriarchy—to name a few. Zinn is hardly the first woman to notice that gender—and the stereotypes it forces people to contend with—can have a tragic impact on females. Women, after all, are statistically far more likely to be sexually assaulted, have undiagnosed mental illnesses, and be victims of intimate partner violence. Zinn’s collection, which is broken into multiple parts, touches on all of these circumstances. A repetitive move for Zinn throughout her entire collection is the incorporation of references to popular media and figures, both literary and real. This use of intertextuality is a powerful choice. How better to relate to readers than through the use of media they’re already familiar with? From children’s stories to comic books, Zinn spans several genres, and uses each of them well.

In chronological order, Zinn’s first reference occurs in her poem “Salt Lake City, UT has the world’s largest collection of horned dinosaur fossils.” She writes an imagined, lengthy response to a psychiatrist's question of “why do you think you’re here?” (line 9) using a list ordered alphabetically, from a) to i). This list structure serves to emphasize how much Zinn wants to say, but has been holding back. She starts, “a) because strangers keep reminding me Happiness can be found / in the darkest of times if I only remember to turn on a light!” (lines 11-12). As the list proceeds, she mentions Dumbledore, a deluminator, dementors, the existence of electricity in Rowling’s wizarding world, and the distinction between the books and movies of Harry Potter. Anyone not familiar with the material will still have a sense of what Zinn is feeling (confused, angry, frustrated, lost), but anyone with an understanding will gain deeper insight into Zinn’s mental health and psychiatric experience. She grapples, via Harry Potter, with the idea of light, and whether it is something that can be “turned on,” as the quote suggests. The wizarding world has no electricity, and so has no lights to turn on. Even wizards can only borrow light— not create it. Zinn laments the fact that anyone (like her psychiatrist, as it’s implied) thinks borrowed light is a good enough cure for the darkness of mental illness. Two more references are made in “Depressive,” the second section of Zinn’s collection, both interesting in the fact that they are already part of a larger discussion about mental illness and the way it is portrayed in the media. One is especially on the nose— a critique of the TV show and book Thirteen Reasons Why, titled “Thirteen Reasons Why Hollywood needs to stop glamorizing mental illness.” While this piece does make mention of other media, such as To The Bone, Silver Linings Playbook, and A Beautiful Mind, Thirteen Reasons feels somehow more important, perhaps because of the controversy that surrounds it. Zinn touches on the largest points of this controversy, providing her own list of thirteen reasons why suicide needs to stop being glamorized on television. The list format is again very effective here, though in this case it’s more because a reader can see how many times mental illness has been commercialized for entertainment, and get the sense that it’s happened more times than a single poem could count. Zinn writes, “6. The month after Thirteen Reasons Why hit Netflix, teen suicide rates / spiked by 30%. / 7. Producers removed one scene in response to backlash. And / immediately started on Season 2” (lines 16-19). Also noteworthy in this quote is the line break after “And.” It serves to build a bit of suspense, and breaks up the decisions the producers had made. Throughout Zinn’s book, she explores the damage that poor media representation inflicts on various groups, chiefly women and queer people. Thirteen Reasons combines not only this poor representation, but Zinn’s personal experience with the content presented. Since her goal is to call attention to the circumstances that feed into the American mental health system, the use of a source that some people have described as great media is especially important. In the same section, Zinn writes an “Open letter from a background patient at Arkham Asylum” aimed at the newest Joker movie of the DC Universe and anyone who finds the clown himself a sympathetic or appealing character. She asks, “[Did] we really [need] another movie / humanizing a violent man…Does he think he’s the only one who’s ever been made less than human?” (lines 3-4, and 37). The final line I quoted stands alone in the piece, as a single-line stanza. Not surprisingly, that makes it all the more powerful, as it becomes all the more noticeable. This reference again highlights an overlap between society’s treatment of violent men, sexism, and mental illness, and Zinn’s own experience with all of those things. She deliberately provokes questions, asking what was really necessary about a movie featuring another violent man with a tragic past who left broken women in his wake. She is especially insistent that the conversation which the movie provoked, about mental illness and trauma, does not need to be led by the Joker, or by violent men in general. That the quieter patients, the one who serve as background characters, have much more to add to the conversation that he ever could. However, in a final sad reflection, Zinn acknowledges that if such a movie were to exist, it’s unlikely anyone would want to listen. The Joker, as it turns out, makes an excellent conduit for conversation. He’s marketable. Mental illness is not. Zinn’s collection is a scathing review of the way society currently works against women, in almost every facet of life. She blatantly argues that her anger is valid, and that she is sick of living in a world that tries to prove the opposite. Mental health and gender-based crimes are not something to be mocked or trivialized for the sake of people’s comfort. Rather, they must be shown in full clarity, so that change can effectively address actual problems. It is not a light-hearted journey that Zinn takes a reader on—but it is one worth following.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed