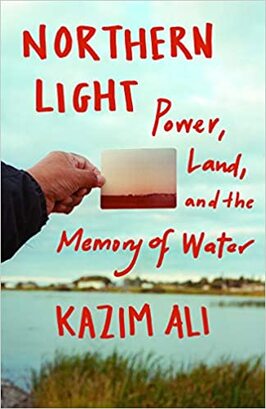

Author Kazim Ali reminds us that, like layers of sediment in the earth, generations of lives are inscribed within the land around us. In his memoir Northern Light: Power, Land, and the Memory of Water, Ali weaves a detailed meshing of historical events, personal accounts, and his own experiences as he searches for answers to the series of questions that led him to Cross Lake and the Pimicikamak community. Questions serve as the guidepost for Ali’s journey; they encourage him to return to the small town of Jenpeg, the provisional community in Manitoba that once supported a hydroelectric dam and powered southern Canadian cities. Jenpeg was Ali’s first childhood home after immigrating from India. It was the place whose lasting memories called him to ask: “What does it mean to be 'from?' What do I think of when I think of 'home?'" (167).

Ali’s boldness shines through in his attempt to answer these questions. Notably, he faces the truth that even as an immigrant, he cannot completely untie his own identity from the ruination of the Pimicikamak and Cross Lake. His own father was a worker on the dam and they, like many of us, were residents of unceded land. Beyond using questions to lead his own personal journey, Ali also uses them as a rhetorical appeal to readers. Alongside Ali, we must ask ourselves similar important inquiries. We must take our own global and introspective look at the multifaceted effects of colonialism. We must face the largely ignored histories all around us. Northern Light comes at a critical juncture in which many are processing an overdue reckoning with a Western history that long favors singular narratives and overgeneralizes the truth and the destruction against Black and Indigenous communities. Ali provokes us to examine these patterns within our very homes. He meaningfully calls attention to failed treaties, mental health crises, the Canadian Indian residential school system, and environmental damage. In doing so, he asserts that repeals have only come recently and almost no meaningful reparations have been made across Canada. Northern Light furthermore takes an important approach to the memoir: Ali gradually removes the focus from himself and instead amplifies the voices of the Pimicikamak people. We meet Chief Cathy Merrick, a tireless fighter for government reparations for failure to meet the promises of the 1977 Northern Flood Agreement. We are introduced to students, neighbors, and families. We see each community member joining to rebuild systems and institutions that had been forced upon the Pimicikamak. We hear of the thousands buried in unmarked graves, disappeared but never forgotten. Alongside these meetings and introductions, Ali incorporates critical historical events and accounts to contextualize the present situation. In shifting his tone between familiar and academic, Ali creates a relatability for readers to latch onto as they experience their own shifting perspectives on colonization. This approach solidifies the undeniable connection between past and present. It reminds us that some things cannot be undone. However, as is mentioned by members of the Pimicikamak community, there is still time to change course. In the words spoken to Ali by Jackson Osbourne, an Elder and historian: “We are not just trying to save the lake and the fish, but we are trying to save ourselves as a people” (69). If we consider the protection of the whole planet, we must also cede that it will require a collective dedication from everyone. As reinforced in Northern Light, our homes are not as something we hold ownership over, but rather own a responsibility to protect. Once we view home from this perspective, it becomes evident that the answers to questions posed by Ali throughout Northern Light cannot be simply unearthed. Perhaps, that is the point of asking them. Our lives are momentary drops of rain into the same immeasurable well of time and history. As we can learn from Ali and the Pimicikamak, these lives are worth preserving.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed