|

by Qwayonna Josephs

Looking back now, it’s crazy to think that my introduction to Black-led stories was a book with a Black man on the cover, holding a gun, a book that was distributed to schools from Scholastic and praised as honest portrayals of inner city kids. Yet, every one of those books I read came from the mind of Paul Langan, a white man who claims in an interview that his intention behind the idea was sparked by minority students wanting to see themselves in print. I’m sure that drew lots of students to the books, seeing someone who looked like them on the cover―it definitely drew me in―but, with maturity and clarity, I now understand the harmfulness of these stories and characters. While trying to show our “experiences,” the books highlight negative stereotypes, slap on a problematic cover, and end up in the hands of impressionable elementary, middle, and high school kids that are desperate to see themselves in a story.

0 Comments

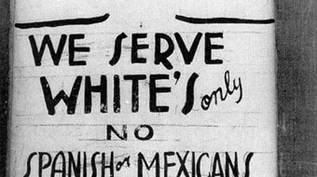

Photo by Emmanuel Ikwuegbu on Unsplash Photo by Emmanuel Ikwuegbu on Unsplash by S. E. Roberts Writing is not a career that has ever paid enough money. Now, I’m not talking about bloggers or journalists, who could certainly stand to make more but don’t necessarily have to. I’m talking about novelists, poets, and short story writers, those artists who are self-advertising on social media, submitting to literary magazines, and publishing books of their work, all in the hope of being recognized and well-compensated for their work.  by Ariana Tucker Go onto any major book-selling website and you’ll probably find a section dedicated to Black authors in the list of genres and subcategories. Amazon calls theirs “Amplify Black Voices” and lists it among other popular keywords like “Award Winners” and “Celebrity Picks.” Barnes and Noble calls theirs “Black Voices” and lists it among other browsing options such as “Large Print Books” and “Trend Shop.” Click on either link and you’ll see popular books written by Black authors, most of which are the same books we’ve been talking about for the last five years. Barnes and Noble is the worst offender of this. On their featured page of “Fiction: Black Voices,” only four were published between 2020 and 2021 (Colson Whitehead’s Harlem Shuffle is their featured book from 2021). The rest are classics by Nella Larsen, Zora Neale Hurston, and Ralph Ellison and books by authors like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Sister Souljah, which were published in the 2000s and 2010s. Amazon at least offers a more up-to-date list of recently released books by month and recommendations from editors and Black icons like Billy Porter and Rick Ross. You can find almost any genre and any subject here, the only difference is that the authors are all BIPOC. by Dominick Marconi  There was this popular meme that recirculated in 2020 which featured a still frame from the Dreamworks animated film Madagascar. It showed the four main characters, Alex the Lion, Gloria the Hippo, Marty the Zebra, and Melman the Giraffe with puzzled expressions on their faces and overlaid text that read, simply: “Why are you black?” Everytime I see it I laugh. Everytime I think about it I laugh. I cannot speak as to why anybody else might find it funny, but to me, the comedy not only stems from the absurdity of the question's nature, but in its truth.  Photo: 12news Photo: 12news I’ve taught freshman composition courses for almost two years now, expecting my diverse body of students from multicultural backgrounds to all coalesce and perform to one standard above all others: White Vernacular English (WVE) or White American Vernacular English (WAVE). As writers, we pride ourselves on being open-minded yet authentic, and we hope our students do the same—as long as they adhere to what we consider valid style of writing. Why have the rigid, outdated principles the foundation of college composition was built on not shifted to accept other vernaculars? |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed