|

by Aleksandr Chebotarev

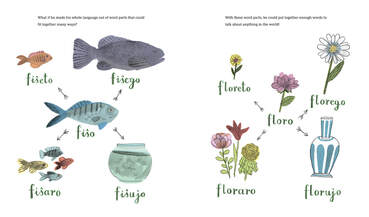

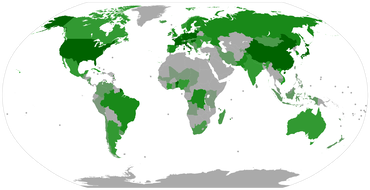

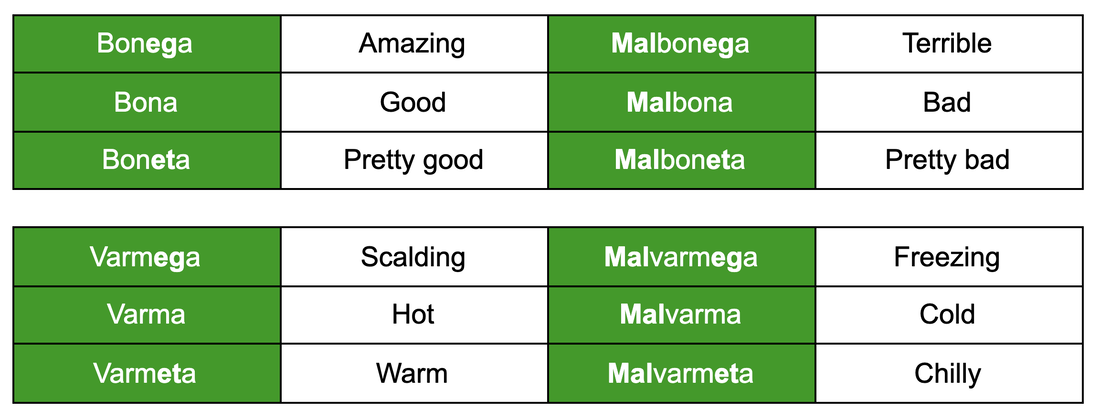

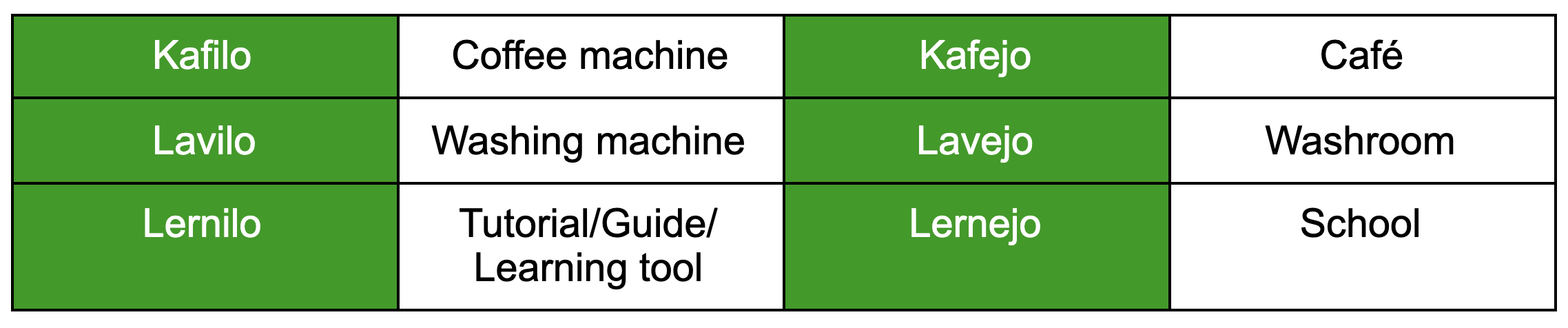

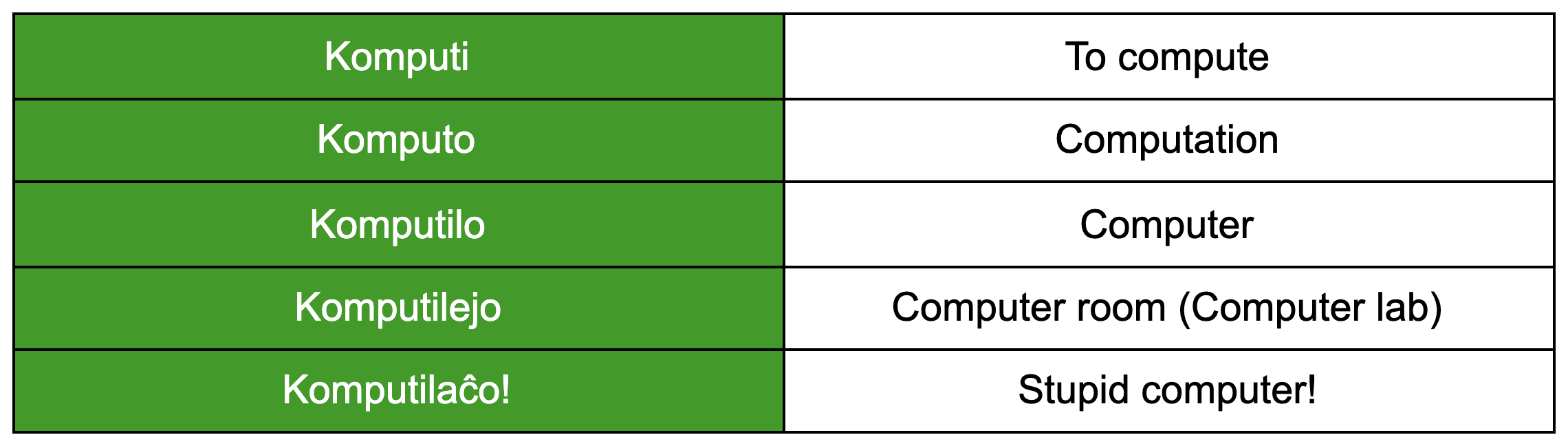

The First Esperanto Congress (1905) The First Esperanto Congress (1905) The unifying language I am referring to is Esperanto, a language invented in the late nineteenth century by Zamenhof, a Polish doctor. He dedicated his life to creating a simple language that maintained all of the depth of any other language. It gained an incredible international following. Eventually, the creator was invited to the first World Esperanto Congress in 1905, a meeting where people of the world could meet each other and interact without language barriers. The World Esperanto Congress has continued taking place every year ever since, receiving up to 6,000 participants each year. The language gained so much popularity that Europe took a vote in the 1930’s on whether or not Esperanto should be their lingua franca. This was blocked by France in hopes to keep French as the lingua franca, and look at what happened: English took their place almost immediately. So they didn’t even get what they wanted in the end. The one time France was supposed to surrender… and they just didn’t? This was their time to shine. If Esperanto’s lingua franca status were never blocked, we would have so many fewer problems. Non-English-speaking immigrants might not be looked down upon in the same way. Being able to communicate with them would allow nationalists to see their humanity. If all people learned Esperanto, rather than expecting American immigrants to learn English, they could assimilate into society much quicker. They’d be able to take a driving test, to vote, to go to school. If everyone in the world started learning Esperanto today, language barriers would be a thing of the past in about a year. Don’t believe me? Try it out for yourself! Esperanto only has 16 Grammar Rules. Learn them this week, start speaking the next, and start making connections with people from around the world. But why Esperanto? What makes Esperanto so special? Is it the first auxiliary language? No, that would be Volapük. Besides its simplicity, Esperanto is perhaps the most morphologically flexible language. In other words, prefixes and suffixes can be tacked on the ends of words to give them new meaning. As you can see, in Esperanto, when you learn one word, you learn six (or more!), and every prefix or suffix you learn multiplies your vocabulary. Why learn 100 words in Spanish when you can learn thousands in Esperanto? Let’s pretend you’re studying Esperanto, and you come across the suffixes -ilo (device) and -ejo (place). Here are some words you would now be able to make. In Esperanto, prefixes and suffixes can be used as individual words, because… why not! They carry individual meaning and can function solitarily, so there's no reason not to use them as words. Therefore, ilo means “machine/device/tool” and ejo means “place.” Of course, these suffixes can be stacked too. Some Esperanto suffixes may be familiar to you. For example, the suffix -ar is used for collections, and you already use it! Isn’t a dictionary just a collection of dictions? Isn’t a library just a collection of libros or a syllabary a collection of syllables? Zamenhof decided to take this a step further, like how the word for “forest” is arbaro, a “collection of trees,” and how the word for “humanity” is homaro, a “collection of humans.”  Rockliff, Mara (author), Dzierżawska, Zosia (illustrator). Doctor Esperanto and the Language of Hope. Candlewick Press, 2019. Rockliff, Mara (author), Dzierżawska, Zosia (illustrator). Doctor Esperanto and the Language of Hope. Candlewick Press, 2019. Esperanto’s morphology is the reason for its success. Zamenhof gave this language to the people by making it morphologically flexible. Of course, the words komputilo and interreto (lit. inter network) did not exist in his time, but the groundwork he laid ensured that it was the people’s language, and it could change as any other language would. This language fascinates linguists like myself, but it is by no means reserved for them. You don’t have to be a linguist or a polyglot in order to learn Esperanto. In fact, there are many Esperantists that have learned Esperanto to discover cultures. They tried to learn other languages, but they were unsuccessful. For some, Esperanto was a last resort for language-learning before giving up entirely. Esperanto gives speakers the joy and enrichment of language-learning without the intimidation. Esperanto remains the most widespread auxlang in history. There are estimated to be two million speakers worldwide, however Esperantists often reject this calculation since it is nearly impossible to calculate. If you wanted to calculate the number of French-speakers, you tally up the population of the francophonie and those certified in French. Esperanto doesn’t have a country nor a widely accessible certification. Duolingo alone has over 750,000 Esperanto learners. Whether the estimate is accurate or not, there are millions of Esperantists worldwide.  Number of Esperanto Association Members by Country Number of Esperanto Association Members by Country The way the world is now, you could learn Spanish, French, Russian, German, and Mandarin and still not be able to communicate with everyone. If we just spent one year learning Esperanto, everyone would be able to talk to every single person on the planet. So when you say you wish that everyone spoke the same language, and I tell you about Esperanto, and you laugh at such a ridiculous idea, I’ll be inclined to ask you what the universal language should be. If your answer is English, then you don’t actually care about the world being connected, you care about it being connected to you. Speaking someone else’s native language inherently results in an imbalanced power dynamic. Think back to the diffident rush of incompetence that would materialize before giving a presentation in Spanish class. That is the habitual state of an individual living and working outside of their language sphere, the geographical No matter the situation, catering to the mother tongue of others leads to a power struggle. In many countries, not speaking the local language complicates getting a job, a driver’s license, an education, and equal treatment both in public and under the law. As an ESL teacher, I have seen all that my students must go through in order to do things that you and I take for granted. Many of my students have trouble finding work, shopping, going to the store, etc. I have one student in particular that can’t get his driver’s license, because the test is not offered in Italian in New Jersey. The state can provide an interpreter, but the test-taker must have taken the test before and failed, proving that they need an interpreter in order to succeed. This may sound like a fix, but immigrants are the busiest people I’ve met. All they do is work, and they rarely have a boss that is forgiving enough to let them leave to go to the DMV at least twice: once to fail and once to have a chance at passing. So, they might have to miss work two or more times as well as pay the $10 fee each time. In other words, they’d have to pay $10 and miss a day of work just to fail a test to get the help they need. This is only one of the many ways that immigrants from different language spheres are not given the same opportunities. Throughout history, the dominating party’s language or dialect tends to gain prestige, causing its imitation. This is known as language shift or borrowing prestige. The Anglo-Saxons’ borrowing of prestige led to the acquisition of French words, like pork, poultry, and beef, which come from porc, poulet, and bœuf, words that would be used when serving French Nobility. Their Anglo-Saxon counterparts, pig, chicken, and cow, were kept on the farm. A similar linguistic transfer took place centuries later when Haitians adopted the word chita (to sit), a deviation of assieds-toi (sit down), into their language. Nowadays, assieds-toi (sit down) can come off as rude, but in the 1800’s, it was belittling. Chita, a portmanteau of the French imperative of s’assoir (to sit), almost definitely entered the language thusly as a result of being uttered in this form more often than any other. In other words, Haitians were told to sit down so much that assieds-toi became their new word for sit. Time and time again, Esperanto has been beaten down throughout its life, but it continues to thrive. Clearly, Esperanto has not yet become the international lingua franca to eliminate language barriers, but it will surely happen. With the recent waves of attention Esperanto has been receiving, this language will become increasingly well-known, and the advent of ubiquitous technology allows users to learn and practice no matter how close they are to other Esperantists. Even offline, the language is making progress in communities, in the sciences, in the arts, in schools, and in universities. Although it may take years or decades for Esperanto to make this change, once we get there, we will not go back. In topology, a mathematical knot is a form that cannot be undone or unraveled. Esperanto is the knot. Once we reach simple, effective intercommunication, we will have no reason to go back. We just have to be patient and work towards establishing that knot. Esperanto in ActionNative Esperanto Speakers

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed