|

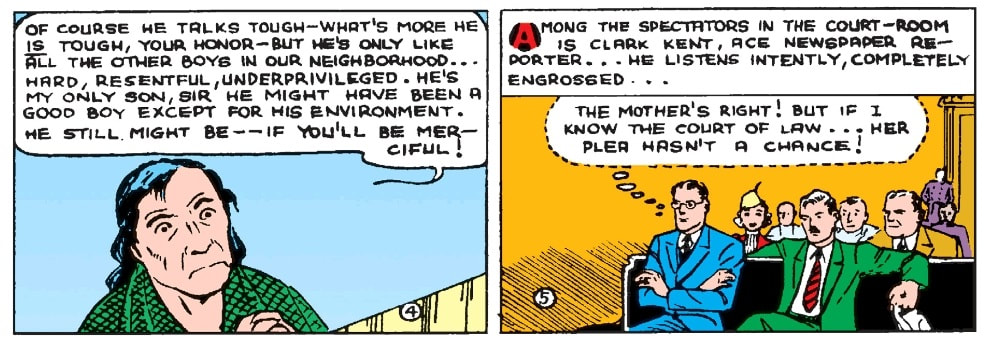

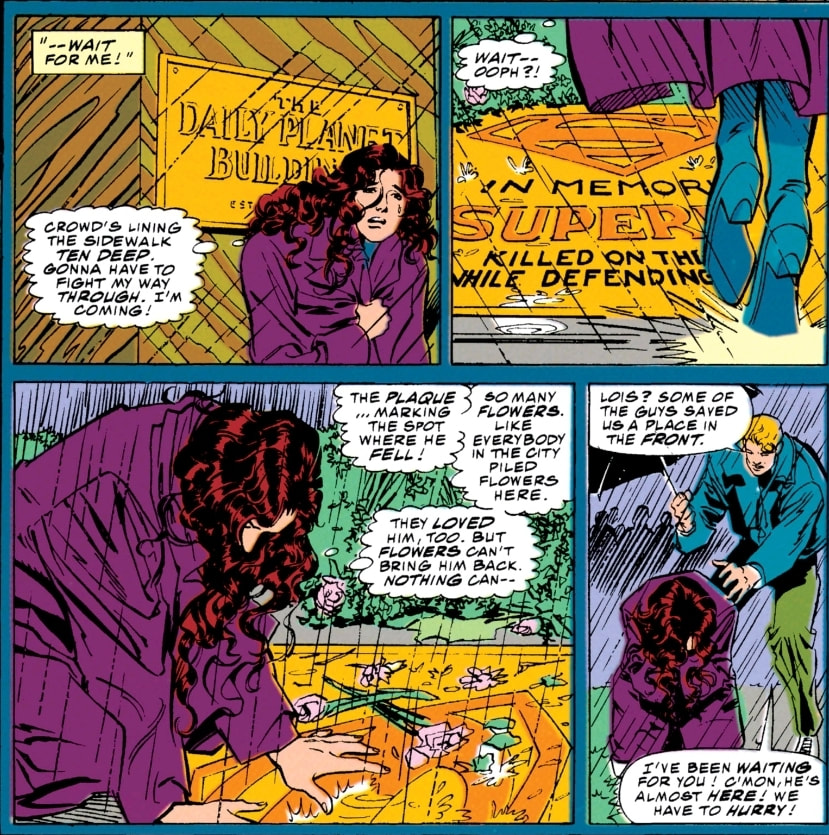

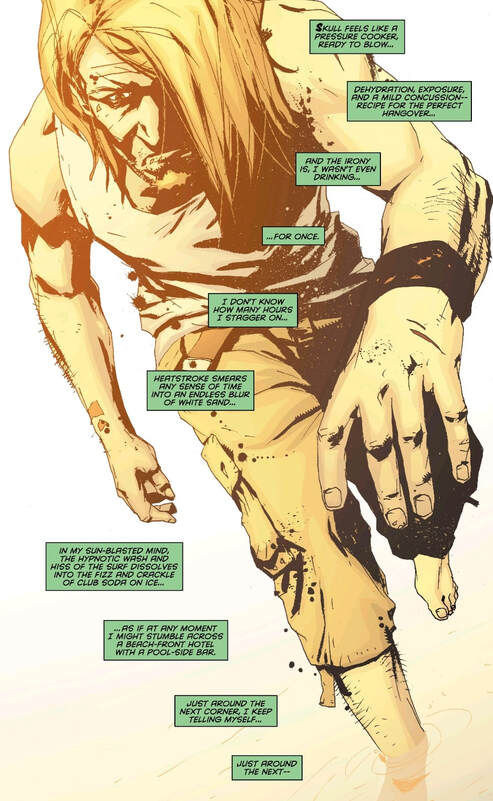

by Thomas LaPorte  Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash A few weeks ago, I started reading “The Death of Superman” story arc. This was a massive comics storyline during the 1990s, one which is still discussed to this day. When I opened the first page, I noticed something I haven’t seen in a long time, something once considered a convention of comics: thought bubbles. See, I have dedicated my comic reading to issues from 2000-2011; by that time, thought bubbles had completely vanished from comic panels. In fact, comic storytelling overall had changed, and I believe a major part of it was due to the extinction of thought bubbles. Since superhero comics first made their appearance in 1938 with the dawn of Superman, thought bubbles were used to convey plot and inner dialogue; they were a staple of the comics genre. However, somewhere in the 1990s, the thought bubbles seemingly vanished from comics. Comic thought bubbles are a hindrance to modern comic books and they should stay gone. The first modern comic book thought bubble appears in superhero comics on page 1 of Action Comics #8 (released January 4, 1939). This bubble is characterized by mirroring the amount of space that a speech bubble has. There is text within this bubble, sometimes in italics. But the defining characteristics of modern thought bubbles are the tiny white bubbles connecting the character to their thought. Thought bubbles started to wane in the 1990s, when comics became engulfed in realism; stories were harsh and dark and devastating. This followed the debut of Watchmen by Alan Moore and The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller, which were stories notorious for bringing comics into a mature and adult world. Storytelling was changing. Comics started becoming adult, and dialogue and text needed to fit that idea. Suddenly, thought bubbles started vanishing. Storytelling got tighter and words were used more efficiently. Thought bubbles were most commonly used for recapitulation, exposition, and word waste. Rarely were they adding anything new to the story; if anything, they interrupted the natural flow of the stories. They were almost amateur. In the above comic following Superman’s death, we see Lois grieving, but there’s really nothing differentiating this scene from any of her other scenes. Her thought bubbles here are nothing but a device to help the reader understand something they don’t need to know. “Crowd’s lining the sidewalk ten deep. Gonna have to fight my way through. I’m coming” literally just told us what we will see happen on the next page after this one. We don’t need that exposition. It is almost demeaning to the audience, as if we aren’t smart enough to understand movement. This is an actual representation of thought bubbles and how they were used and abused. Of course, some were short and sweet, but a good faction were just recapitulation and word waste. I am not against thought in comics; I am against the unnecessary exposition and word waste found within thought bubbles. The solution to word waste became clear when I opened an issue later in the “Reign of the Supermen” storyline. It was a modern text box, not necessarily new to comics, but its newest function was to convey thought—though these thoughts did not recapitulate. Instead, their role was to actually show the character’s reactions and thoughts to events. They were used to move the story forward instead of holding the story back and recapitulating. They fundamentally changed the pacing and movement of stories. This was the way storytelling was meant to be. This is why text boxes are better than thought bubbles. Take this splash page from Green Arrow Year One #2 as an example. Here we get the inner monologue of Green Arrow (Aka. Oliver Queen), which isn’t explaining he just got trapped on an island last issue. Instead, it is telling us Oliver feels like he’s hungover, but not from drinking. “Skull feels like a pressure cooker." We’re actually gaining something by learning what Oliver feels and senses. “As if at any moment I might stumble across a beach-front hotel with a pool-side bar. Just around the next corner, I keep telling myself…” We have gained so much on this page. We learn what Oliver wants, what kind of person he is: rich, and a frequenter of fancy hotels. Yet, at the moment he is not. He is isolated. This is how thoughts should be used. To give us real depth into a story. Anything less is not giving enough credit to the character.

When comparing these two different techniques in thought portrayal, I realize what I want from comic character thoughts is depth; I want every word to mean something because every word should mean something. Especially when there aren’t many words on a page to begin with. To me, thought bubbles did not have this effect; however, text boxes do. The modern storytelling device is effective and allows for deeper relations to characters. I feel like I truly know characters that use this method. For this purpose, thought bubbles should stay gone. Long live text boxes!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed