|

by Mark Krupinski  “Anything and everything can be art!” is, I feel, a deceptively sinister phrase. You could substitute the rather generic “art” in this situation with your medium of choice, be it poetry, film, literature, or what have you, and the situation remains unchanged. It seems innocuous at first, even encouraging. Anything can be art; no matter how lost you may feel, no matter what vision you lack, your expression has merit. You exist and you are valid. As someone who has spent more time than perhaps he’d like to admit pacing fretfully to and fro, hyperventilating into a McDonald’s bag because the words don’t sound the way they’re supposed to, I understand. Writing is a painful, clumsy, often fruitless task, so positive affirmation is as valuable as it is rare. But there’s a danger in creating that sense of comfort, tossing standards by the wayside in favor of blind positivity and confidence. The idea that everything, every single careless, thoughtless, witless, messy, wishy-washy, meandering, pointless thing is art gives me pause.  Behind the smokescreen of good feelings and free love lies a latent nihilism. Everyone needs to feel good about everything that they create, and for that to happen, objectivity must die. Painfully. Dragged kicking and screaming to the top of a sacrificial altar, where its living guts are ripped out for all to see. And when the assorted viscera hits the floor, the leftover stains will be mounted, framed, and sold for millions of dollars. It didn’t require any intent or practical skill to create, but hey, it’s cerebral! Which isn’t to say that traditional standards are the end-all be-all. It’s important to have some form of objective standards, but there’s also nothing wrong with enjoying good old fashioned trash. I personally consider The Room to be one of the most important films ever made, and anyone who has experienced it firsthand will understand why. The Room is notable, not because it is good, but because it is bad. Not just bad, terrible. Heinous. One of the worst things a human has ever created. It breaks every rule in the book of filmmaking, yet still manages to be one of the most fascinating, entertaining, endlessly quotable pieces of cinema ever made. It’s been called “The Citizen Kane of bad movies,” a statement that isn’t even remotely hyperbolic, but the only reason it succeeds in the face of breaking so many film school rules is that said rules exist in the first place. Without structure, order, and an established standard of quality, The Room is no more special than the thousands of forgettable, corporate-mandated action movies or bland, assembly-line rom-coms that are dumped into theaters every January. Don’t get me wrong, subjectivity is important. It’s what allows art to be the flexible, personalized, undoubtedly real thing that it is. Without subjectivity, art loses its point, and in some cases, its purpose. The only major flaw subjectivity presents, however, is that it can be applied to literally anything with wild abandon, and there’s not a goddamn thing anyone can do about it. As I write this op-ed, I could easily pass the whole thing off as a work of performance art. The black coffee I’m guzzling down to stay awake and focused is symbolic of how we sometimes need to swallow life’s bitter realities to achieve our goals. My neglected succulent, a metaphor for my personal passions cast to the wayside in favor of more pressing obligations from school and work. What I’m doing right here? This is art. Really complex, visceral, high-brow stuff, and there’s literally no way for you to prove otherwise.  I’ll admit, it feels strange to be arguing in favor of rules and regulations, like I’m the bad guy in Footloose or something, but you can’t argue with the results; constraint inspires creativity, plain and simple. I feel like the seminal example is Ren & Stimpy; when it first aired on Nickelodeon in the early 90’s, the network censors did everything they could to stifle the expression of the creative team and keep things safe and soft and sanitized for the precious children who would tune in to watch the show each day. This forced the writers to get creative; they’d stock episodes with gags that were intentionally profane which they had no intention of ever airing, just so they could have bargaining chips when haggling with the folks from standards and practices. They’d have to find creative, subtle, and subversive ways to sneak their off-color toilet humor onto the air, and that’s why the show is by and large remembered as a classic. Compare that to the eventual revival, Ren & Stimpy Adult Party Cartoon, which aired on SpikeTV (according to promotional materials, “the first network FOR MEN”). Gone were the network constraints (for the most part), and along with it, any semblance of wit. The writers no longer had to challenge themselves and think of creative ways for the characters to act naughty; here, they were just allowed to go all out, resulting in a show that had all the depth of a bottle cap and less than half the value.

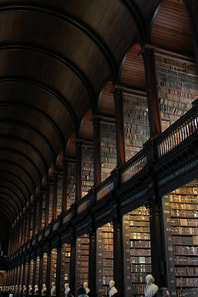

Writing is an inherently structured art form, even if that structure is having no structure. Poetry or prose, fiction or nonfiction, creative or technical or even academic, no matter the genre of writing you choose to work in, there will always be some sort of existing standard of quality. That’s how we know these genres exist in the first place, because we’ve developed a naturally occurring means of ranking and sorting written works based off of diverse and varied criteria. These rules will exist no matter how badly we try to convince ourselves that they do not, and attempting to do away with them altogether doesn’t do anyone any favors. In order to break the mold, there has to be a mold to break in the first place. Even if you’re the kind of person who views The Room as a subversive masterpiece of free expression, your personal sense of standards are perfectly valid, especially compared to having no standards at all. Writing has the potential to be a miraculous, life-changing, transcendental thing, but that’s all done away with when we set out to demolish the very systems that allow us to designate it as such.

1 Comment

9/26/2019 10:51:15 am

Glad you pointed out the need for a glass to hold our water of life (shared creative works that mutually inspire). We need to remember that the original meaning of the word "art" was "skill" -- as in martial arts, theatre arts, magical arts etc. Schools, with their emphasis on "personal" creativity (overtly therapeutic) fail to teach the skills of painting, writing, making verse and so on, skills which were honed over decades of commitment during the high ages of classical art. So quality can't but decline. If a culture says ANYTHING is art, then nothing is - it has no art.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed