|

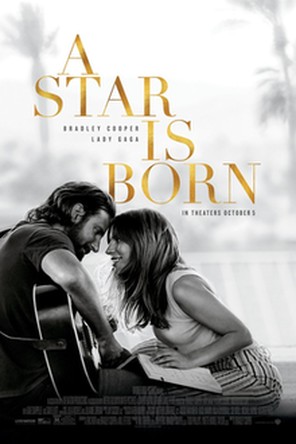

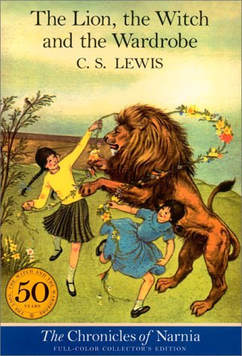

by Leo Kirschner  There is no such thing as originality! Don’t believe me? Go visit your local cineplex. 2018 brought us A Star Is Born, the fifth - yes fifth! - film adaption of the tragic love story between a celebrity in decline and his younger female protege. Want more proof? Robin Thicke’s hit 2013 “Blurred Lines” sounded very much like Marvin Gaye’s 1977 single “Got To Give It Up.” The courts thought so, too. Even in literature, Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight begat E.L. James’ Fifty Shades of Grey. British folklore, mythology, even The Lord of the Rings found themselves interwoven in JK Rowling’s epic Harry Potter-verse. We are living in a culture where ideas are recycled and creativity is not highly regarded. I’m not the only one who believes this is true. In Mark Twain's Own Autobiography: The Chapters from the North American Review, the famed writer offered up a similar viewpoint: “There is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope... We keep on turning and making new combinations indefinitely; but they are the same old pieces of colored glass that have been in use through all the ages.”  Photo by Neil R. via Flickr Photo by Neil R. via Flickr Twain’s stance on the existence of originality is further fueled by Christopher Booker’s 2005 book The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. Booker points to the common story plots found in all of the world’s literature: “Overcoming the Monster,” “Rags to Riches,” “The Quest,” “Voyage and Return,” “Rebirth,” “Comedy,” and “Tragedy.” Their origins stem from historical events, philosophical beliefs, and cultural myths passed on from generation to generation. As a society, we are compelled to re-tell tales and fables and epics to offer wisdom and retain our identity. But we also do it to gain insight and find meaning in ourselves and our actions. So it’s only natural storytellers to digest what was learned, interpret the findings, and present it in a new way for new audiences. Only that’s not originality. That’s something literary educators call “intertextuality.”  Ever read a book or watched a film and wondered to yourself, “where I have seen this before?" Chances are you have. That’s where intertextuality comes in: taking a previous story or “text” and connecting to it in some manner. You may allude to it (artists call this “homage”), you may directly quote from it (Hollywood calls this “reboot”), you may imitate it (scholars call this “pastiche”), you may make fun of it (comedians call this “parody”) or you may blatantly rip it off (lawyers call this “plagiarism”). C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is basically a retelling of Christ’s crucifixion from the Bible. Bridget Jones’s Diary is a modern interpretation of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. And Bradley Cooper’s aforementioned A Star Is Born doesn’t just reimagine the original 1937 story and characters in a contemporary 2018 setting; it’s a remake so close to the source material that it even credits the original writers for the plot. But in searching for deeper meaning and understanding through the re-telling such stories, you would think that greater enlightenment would result from our efforts. No.  Photo by Scabeater via Flickr Photo by Scabeater via Flickr Not only do we not strive for originality, but our culture also doesn’t place much emphasis on creativity, either. “Out of the box” thinking is only accepted in deductive reasoning and problem-solving. Elsewhere, artists and authors are encouraged to follow established rules. In writing, such rules create “genres” (remember, your Lit class taught you that genre means “a category of artistic composition characterized by similarities in form, style, or subject matter.”) Following the rules of any genre inherently limits originality. So your “original” work is doomed to be “derivative,” a copy or imitation of something else (I’m looking at you again, Bradley Cooper!) Why do so many horror stories take place “on a dark and stormy night”? Because storytellers use something universal like the weather as a sort of shorthand to artistically let you know that something “ominous”, “foreboding” or just downright “scary” is going to happen (in literature, that’s called a “motif”, using something concrete and natural to represent something abstract and unnatural.) So if you want to write that horror story, it won't be considered as much lest it contains some of those motifs and horror genre trappings. And of course, you will need a hero confronting an evil foe (see seven basic plot #1 “Overcoming the Monster”.)  Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia So, how about mixing it up and changing the rules? Chances are, that too has already been done to create “cross-genres” such as Science-Fiction, Romantic-Comedy, Dark Fantasy, etc. Here, writers must play by another set of rules already established by others. Portuguese Nobel prize winner Jose Saramago, when asked about his daily writing routine commented, "I write two pages. And then I read and read and read." This reinforces the point constantly made by writing professors: by reading the works of others, you will be studied in effective storytelling. As a result, you can become “inspired” (hello, intertextuality!). So, in essence, we are all just exchanging ideas among one another, as Twain remarked all those years ago. It is clear that our ideas are not entirely unique. Our movies, music, and literature follow basic formulas and templates handed down through the generations. In fact, this rant on the lack of originality… isn’t even original. But what allows us to reconcile such repetitiveness is the authenticity that each of us brings to recycled ideas. We inject our own truth and insight into our creations. We shine a light onto our own frailties, vulnerabilities, and shortcomings in our stories. We examine ways to improve the human condition and evolve our society. The resulting work, however much unoriginal, is told through our own unique voice. The New York Times names authors Dave Eggers and Georges Simenon as prime examples of authors who are adept at bringing truth to their wholly repurposed narratives. Adherence to conventionality is accepted as long as the underlying truth has integrity.  Think of it as a cultural relay race, where the idea baton is handed off to the next participant, who then runs off with it before passing it along to another. Each new unique contribution inspires another contribution. In effect, this allows our contributions (read: “original ideas”) to live on beyond ourselves. So, if history and human nature have taught us anything, it’s a safe bet that more retellings of A Star is Born will be coming to a theater near you.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed