|

By Jessica M. Tuckerman Here’s a brief description of one of my favorite stories: Desmond Miles just escaped from Abstergo Industries, the modern day face of the Knights Templar, after he was forced to live out the genetic memories of his ancestor who fought in the crusades. He escapes with Lucy Stillman and two others who help him to reach a secluded cave where Desmond relives the memories of Ezio Auditore da Firenze. The story jumps between Ezio’s story in the Italian Renaissance and the cave where Desmond is desperately trying to find an alien device which will destroy the world if it falls into the wrong hands. By reliving Ezio’s memories, Desmond hopes to find where the device is hidden before Abstergo catches up to him. The story is full of twists and turns. I actually cried when Ezio, the narrator for much of the story, had to watch his family hang in the middle of Firenze. I love the plot, I love the framed narrative, I love seeing Italy during the Renaissance. I was consistently surprised throughout my first reading of the piece and I truly recommend that you pick it up. The story is from Assassin’s Creed II. A video game. The Electronic Literature Organization defines e-lit as “works with important literary aspects that take advantage of the capabilities and context provided by the stand-alone or networked computer.” Can I find any important literary aspects in Pong? No. Because it’s digital tennis. But I can absolutely find literary devices in more modern games, Assassin’s Creed and BioShock among those. Consider that the assassinations, the gun shots, the knife fights, the murder, death, and fighting which are prevalent in today’s games are just symptoms of it being a game in the same way that turning a page is a symptom of the book as a medium. Take them out of the equation and look at the stories.

The depth of characterization revealed to you in a game is dependent on the level of interaction from the player. If you-the-player do not complete the missions given to you by the minor characters, like your mother and Leonardo DaVinci in Assassin’s Creed II, you will only get the characterization given to you in the major plot line. Playing through only the major plotline of Assassin’s Creed II means that you will see both a dedicated and vengeful Ezio Auditore, as he learns his skills as an assassin and then systematically takes out members of the Borgia who had betrayed his family. But if you collect all of the pigeon feathers to complete your dead brother’s collection, you will have a special moment with your mother, who has not talked since the death of her husband and two of her sons, showing a more tender side to the assassin. But characters don't make the plot.

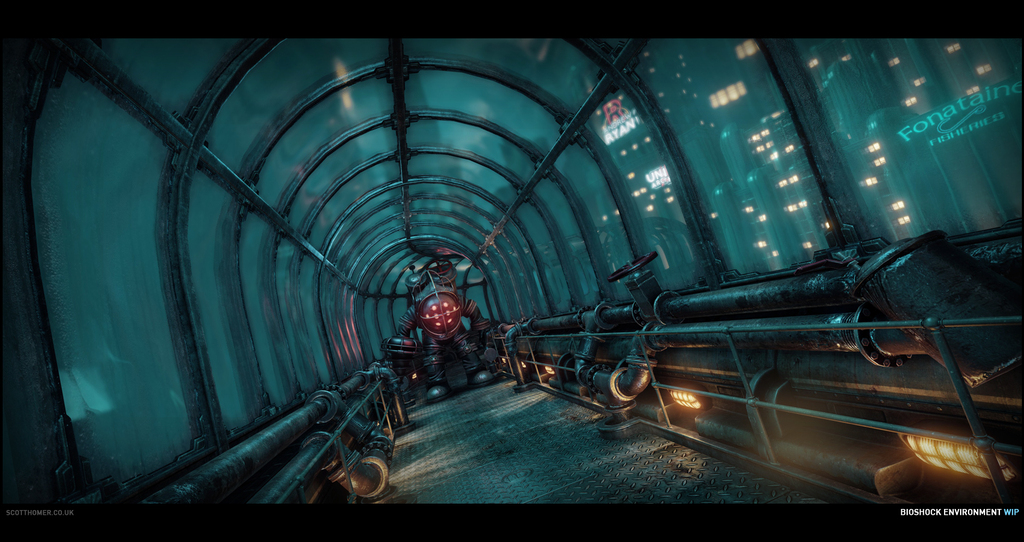

Plot and characters are surface aspects of literature. Every story has them. The best stories, however, have a little more meaning to them, and ask the player/reader a big question. In BioShock, a first person shooter, you play as Jack, who just crash landed in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and happened upon the underwater city of Rapture. Obviously designed to be utopia away from the prying eyes of the government and their laws, Rapture is now crumbling as seen not only from its drug addicted residents but also from the many leaks around pathways. You are guided by Atlas who asks you to hijack a series of rooms and items on your descent through Rapture. Each time he asks you to do something required for the story to move forward he states “would you kindly.” Each time you obey. Although, early in the game you assume it’s because you-the-player want to move through the game. But if you-the-reader, the analytical player, listen closely: Atlas doesn’t always say “would you kindly.”

“Would you kindly kill Andrew Ryan?”

The obvious symbolism in the game is with the crumbling infrastructure of Rapture. As you walk through its underwater passageways, there are leaks, rust, and just flat out sunken areas. You can peep through windows to see the broken city at the bottom of the sea and glean that its physical appearance is representative of its social and economic situation as well.

In Assassin’s Creed II, you need to use your setting of 15th century Italy, to climb up on the terra cotta roof tops and hang precariously from window ledges to air assassinate your foes. You also need to find corners, crowds of people, haystacks, and other hiding places to lose your enemies or trap them.

You mean like—the way a video game is a piece of software that requires input into a device connected to a computerized platform?

Stop thinking of games as games that children play with monotonous and repetitious game play and start thinking about games as electronic choose your own adventure literature. The meanings we can glean from video games depend on the interactions of the player as opposed to non-electronic literature in which we can only bring our own experiences and prejudices. If you play more, you discover more. If you read more, you can only discover what the author left for you. So, would you kindly consider video games a form of electronic literature?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed