|

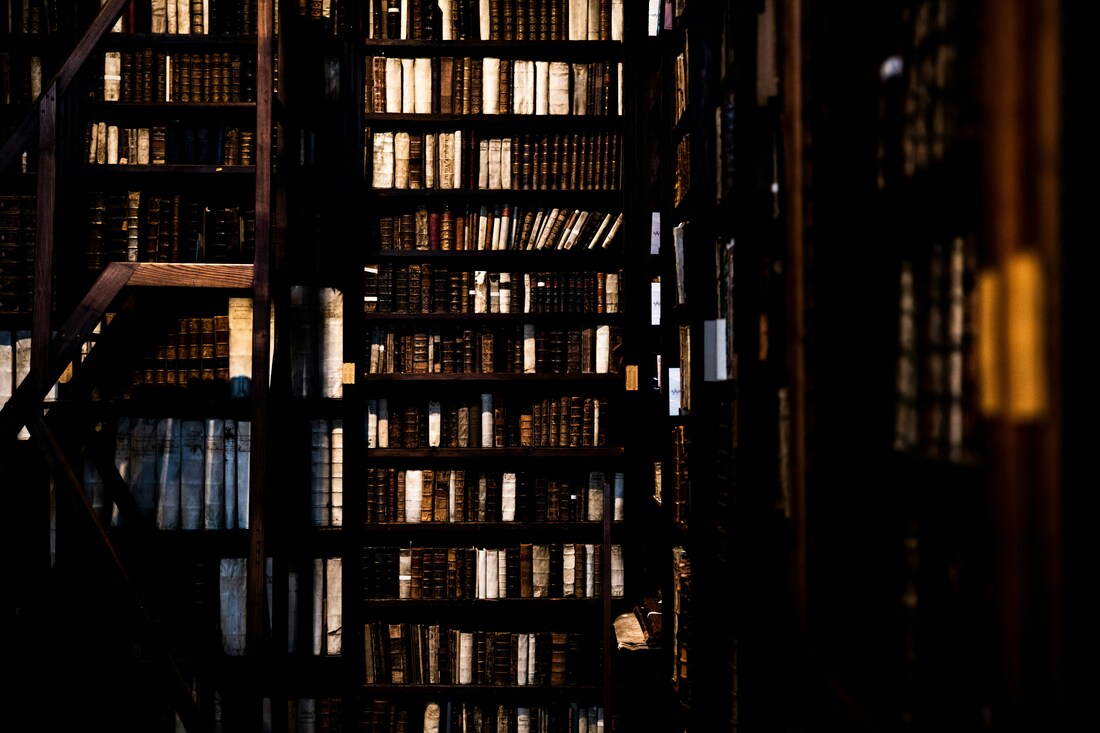

by Allison Padron For some, the words "literary fiction" brings up images of tweed jackets, learned academics, dinner conversations over wine, and personal libraries filled with only the finest of literature. The "literary" label is usually applied by critics to novels considered so intellectual, so linguistically beautiful, and so meaningful that they apparently need to be separated out from the mass-market, "mindless" genre novels. The debate about the distinctions between genre fiction and literary fiction still rages (as it likely will for many more years), with some classifying literary fiction as an entirely different genre, others as a continuum with genre fiction, and still others saying the "literary" quality is something that a novel of any genre can possess. From everything I’ve read on the subject, though, no one seems to have come up with a clear definition of literary fiction (other than "not genre fiction"), which begs the question: why call anything literary fiction at all? Steven Petite, in his op-ed on Huffpost, attempts to clarify what the line is between genre and literary fiction. According to Petite, literary fiction “separates itself from Genre because it is not about escaping from reality”. Unlike genre fiction, "literary fiction is comprised of the heart and soul of a writer’s being, and is experienced as an emotional journey." Genre fiction, on the other hand, exists primarily to provide "entertainment… a riveting story, an escape from reality." It isn’t impactful, it "does not deliver a memorable experience that will stick with you emotionally for the rest of your life." And while I give Petite credit for claiming that neither kind of writer is better than the other, I take issue with his interpretation of what the purpose of genre fiction is. The line between genre fiction and literary fiction is, in reality, so blurred that it’s almost nonexistent. All fiction, literary or not, is about escaping from reality to some degree, since you are entering a world that is not yours. Even if that world is indistinguishable from our reality, you are temporarily living another life and engaging with problems that are not your own. And claiming that genre fiction is primarily for entertainment–that it doesn’t deliver memorable emotional experiences and doesn’t contain the heart and soul of its writer–is far too simplistic of an interpretation. Even within a single genre, like fantasy or science fiction, there are some books that are written or read solely for easy entertainment, and others that deeply engage with issues we face in our world, that make readers cry and laugh, that stick with the audience for the rest of their lives. Some make commentary on our world or the human condition, like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Some, like The Lord of the Rings trilogy, celebrate hope and persistence in the face of evil. Others are influenced by historical events, like George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series. Readers sympathize with Frankenstein’s monster, and are horrified by Offred’s life in Gilead. They celebrate the Fellowship’s triumph over Sauron, and grieve the loss of Ned, Robb, and Catelyn Stark. The reasons we read and write, and the books we choose to engage with, are so subjective and personal that it’s irresponsible to claim that genre fiction doesn’t contain the heart and soul of a writer– and that literary fiction always does. None of these distinctions hold any water when you take a closer look at them.

As someone who primarily writes fantasy, these attempts to draw lines between books that are genre and ones that are literary are discouraging– verging on demeaning. To hear that my books will not deliver a memorable experience, that they aren’t composed of my heart and soul, that they’re an escape from reality and solely for entertainment, not for deeper meaning, is hurtful–and more than that, it isn’t true. The characters I write contain parts of me, parts of the people I love, parts of this world that I like and dislike. I tackle real-world issues in my writing: family relationships, religion, homophobia and queerness, patriarchy, oppression. I don’t write to escape this world, I write to engage with it on a deeper level, to explore influences from my life in a different context. My books are meant to be art, to be self-expression and exploration, to be vivid, emotional storytelling that ultimately examines what it means to be human. In no way am I claiming that I write world-shattering works of literature, but I do know that I’ve written and read "genre" books that do everything these distinctions claim only literary books can do. So, if there’s no clear distinction to be made between genre and literary fiction–if so many people who talk about literary fiction claim it’s "hard to define" (as Celadon Books does), or say that it’s a category of writing that can be applied to any genre, then why are we making a distinction at all? What’s the point? Every piece of literary fiction falls (even if only partially) into a genre. Some genre fiction breaks the mold, engages in a different way with language or character or plot than the stereotypical book in its genre. So, why create some kind of binary between the two? In my opinion, there isn’t a point to this long-standing debate. Classifying things as "literary" or "genre" is an exercise that goes nowhere, that serves only to divide writers and readers. It is my firm belief that we should evaluate each genre individually for the good and bad writing it contains. If there are well-written books within that genre that focus on language and expression, that subvert expectations, then they should be praised and awarded–but there’s no point in separating them out into an entirely different pseudo-genre and calling them "literary." Within every genre, there are some books that are meant for entertainment and others that are meant to explore the human condition; both kinds have merit, and one does not have to be "distanced" from its genre by calling it literary fiction. The idea of an elite category of fiction that is "literary"–which is somehow separate from genre–is a remnant of the past, of the pseudo intellectualism and gatekeeping of the "elites" who wrote "serious" novels. As Joshua Rothman points out in his excellent piece for the New Yorker, the "distinction between literary fiction and genre fiction is neither contemporary nor ageless," but a centuries-old, constantly shifting debate between the old-guard and the new arrivals. And honestly, I think the entire thing is pointless. Some books are certainly more well-written than others, but it’s untrue and far too simplistic to say that whole genres are better than others, especially when the idea of genre is constantly changing and when no book perfectly fits the requirements of its genre. It’s time to evaluate books based solely on their individual merit–and to lay this endless, meaningless debate about the definition of "literary fiction" to rest.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University's Master of Arts in Writing 260 Victoria Street • Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 [email protected] |

All Content on this Site (c) 2024 Glassworks

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed